Retail Loss, Safety and Security

This Working Group is focused on enabling retailers to understand, measure and control the increasingly complex array of loss challenges they now face.

From incidents of violence against store team members to corporate fraud events, the retail risk landscape is forever changing, requiring those tasked with its management to constantly learn, adapt, and respond.

By listening to the evolving needs of its members, this ECR Working Group provides a forum for loss prevention leaders to share, engage and learn from an innovative research agenda.

Research papers

Our research papers offer groundbreaking insights and actionable outcomes to help retailers and their partners better manage the many ways in which profits can be negatively impacted by all forms of retail loss. Produced by some of the leading academic experts in the field of retailing and loss prevention, they are all free to download.

Our Meetings

ECR Retail Loss Group regular working group meetings provide an opportunity to network with industry peers, hear updates on the latest research and sector initiatives, and development new skills and insights. All retailers, CPGs and academics can participate at no cost.

Innovation Challenges

Blog Retail Loss, Safety and Security

Podcast Retail Loss, Safety and Security

What is Retail Loss or Shrinkage and Why Does it Matter?

Retail loss, sometimes referred to as shrinkage, is the reduction in inventory resulting from many factors such as theft, damage, or administrative errors.

For retailers, it matters because it directly impacts profitability. Retail losses can account for a significant percentage of total sales, translating into billions in losses worldwide.

As a result, reducing shrink is crucial to maintaining healthy margins and ensuring the sustainability of their business.

Understanding retail loss and developing effective prevention strategies can also improve customer experience by ensuring product availability.

What Are the Financial Costs of Retail Shrink on Business?

Retail losses can have a significant impact on businesses: eroding profit margins, inflating operating costs and demanding increased spending on security and loss prevention strategies.

Globally, the cost can run to billions of euros lost each year. In turn, this can ultimately result in higher prices for shoppers.

The percentage of total sales impacted by shrinkage can vary widely depending on the retail sector and specific operational circumstances.

Failing to effectively address retail losses can lead to a cycle of compounding costs and lost sales.

Proactive shrink management is not only about reducing losses but also about enhancing the overall financial and competitive health of a business in the retail market.

What are the Potential Causes of Retail Losses or Shrinkage?

There can be many causes or sources of retail losses, some of which we will outline below. Each type requires specific strategies for mitigation.

Understanding these various sources helps businesses develop comprehensive approaches to effectively reduce overall shrinkage and protect their profitability.

Shoplifting and Customer Theft

Shoplifting ranges from opportunistic theft to organised criminal gangs. It can be a significant contributor to retail losses.

Strategies to mitigate this risk include visible security measures, staff training in theft prevention, and customer service strategies that deter potential thieves.

Such measures can increase operational expenses and affect the shopping experience for honest customers.

Employee Theft

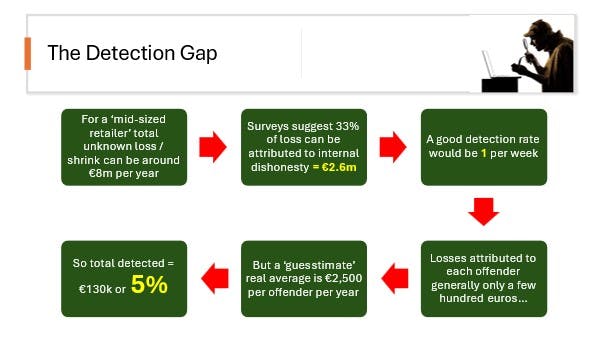

Internal, employee crime can include theft of merchandise or cash and processing of fraudulent transactions. It may stem from vulnerabilities in store policies or surveillance.

Preventative measures include thorough vetting during hiring, regular audits, and fostering a workplace culture that discourages theft.

Vendor Fraud and Supply Chain Issues

Vendor fraud involves deceitful activities by suppliers, such as overcharging, billing for undelivered goods or supplying counterfeits.

Other supply chain issues that might also contribute to shrinkage include goods that are lost or damaged in transit.

Strengthening partnerships with suppliers and maintaining rigorous checks on goods received can help mitigate these types of losses.

Administrative Errors

Administrative errors such as pricing mistakes, inventory mismanagement, or mishandling of paperwork can significantly contribute to retail losses.

Such mistakes can lead to discrepancies between actual and recorded stock levels. This can lead to shrinkage and out-of-stocks.

Streamlining inventory management processes or automated systems, alongside regular staff training can reduce these types of errors.

Data Theft and Cybersecurity Risks in Retail

With the increasing number of digital transactions comes an increased risk from cybersecurity threats.

Data theft can include unauthorised access to customer information, credit card fraud, or breaches of employee data.

Protecting customer and company data is vital for managing retail losses, maintaining trust and ensuring compliance with the highest regulatory standards.

Retailers must invest in strong cybersecurity measures, including secure transaction processes and compliance with data protection regulations, to guard against these risks.

What New Types of Fraud Are Retailers Facing Today?

Retailers today are locked in an arms race with increasingly sophisticated fraudsters. Staying ahead requires continuous updates to security technology and methods.

New retail loss risks come from the likes of synthetic identity fraud, E-commerce and returns fraud, account takeover attacks, and the use of deepfakes or AI for scamming.

The evolving consumer landscape such as the increase in online and hybrid shopping models can amplify those threats.

Retailers must adapt to these challenges through advanced security technologies and fraud detection systems.

Additional staff training to spot fraudulent tactics and maintain rigorous security practices can help control retail losses.

How Are Changing Consumer Behaviours Impacting Retail Security?

The rise of online shopping and contactless payments has been welcomed by millions worldwide. However, it presents new challenges for managing retail losses.

One example of this shift in preferences is that today many consumers like to browse in one channel and purchase in another (e.g., online to offline).

This omnichannel shopping complicates inventory tracking and increases opportunities for fraud at multiple points, from order to delivery.

Meanwhile, online shoppers expect fast, flexible delivery and return options. The logistics of securing the last mile of delivery and verifying customer identities can be challenging.

Retailers must adapt both their physical and digital security measures to effectively manage the risk of rising retail losses.

How Does the Increase in Online Shopping Affect Physical Store Security?

The increase in online shopping is reshaping the retail landscape, leading to a significant impact on physical store security in often nuanced ways.

Changes in store layout and function, as some become showrooms or pickup locations for online purchases, require changes to how products are displayed, tracked and stored.

The blending of online and physical sales channels can complicate inventory tracking and lead to new systems of inventory management and potential sources of shrinkage.

Meanwhile, loss prevention professionals are expected to adapt and expand their roles to include cybersecurity responsibilities and omnichannel risks.

Retailers need to balance resources between online and physical security to control retail losses and protect all aspects of their business.

What Strategies Can Retailers Implement to Mitigate Return Fraud?

Tackling return fraud, without harming legitimate online sales, requires retailers to refresh and maintain clear, robust returns policies.

Time-limited returns and detailed tracking systems, with streamlined tagging and condition checks can help to control retail losses.

While technology is often a default solution, empowering employees with enhanced staff training may also help to prevent shrinkage.

Staying on top of return fraud is crucial for retailers as they balance protecting their margins with a commitment to customer satisfaction and service excellence.

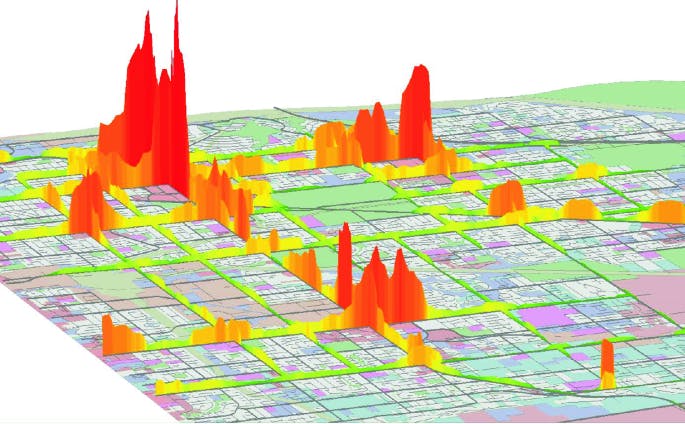

What Is Risk Modelling and How Can It Aid in Loss Prevention?

Risk modelling involves using statistics to predict and quantify potential losses. In retail, this can help allocate resources and reduce shrinkage through data-driven decisions.

Using historical data and predictive analysis, retailers can make informed forecasts. And, as a result, take proactive action to reduce shrinkage.

By understanding where and when risks exist, businesses can adjust staff scheduling, security camera placement, and other loss prevention measures.

Risk models help retailers simulate various 'what-if' scenarios, such as rapid changes in technology or shifts in consumer behaviour, and predict their impact on potential losses.

This approach allows businesses to proactively identify potential threats and vulnerabilities, enabling more informed decision-making and strategic planning to mitigate those risks.

What are the Future Trends in Retail Loss Safety and Security?

Future trends in retail loss safety and security will be shaped by the increased use of AI and machine learning. This will impact both the types of risks and ways to tackle them.

These technologies allow retailers to analyse huge volumes of data from multiple sources, including CCTV, point-of-sale records and online behaviour.

So that retail loss professionals will be better equipped to predict and identify suspicious activities more effectively.

Meanwhile the integration of IoT devices for better asset tracking, and enhanced data analytics for real-time security management will bring about changes in retail loss management.

Sustainability is also likely to have a huge impact on retail loss prevention, as businesses strive to reduce waste and live up to environmental promises.

For a more detailed understanding of these trends and to explore case studies and expert analyses, the ECR Retail Loss community will continue to provide extensive resources to keep you up to date on the latest thinking on retail loss prevention and security.

FAQs Retail Loss, Safety and Security

Given the depth and breadth of TRL, it is perhaps not surprising that some companies are reluctant to adopt this approach. Recent research looked to identify what were viewed as the main barriers to adopting TRL. The main challenge was found to be not necessarily a lack of relevant data, but more one of data availability, accessibility and collation – pulling the relevant data together to populate the TRL typology. A second issue was found to be the impact of organisational inertia and competing priorities: there are hundreds of years of legacy to deal with when it comes to changing how retail businesses understand, measure and control losses. In addition, responsibility for various types of loss can be scattered across an organisational structure, making it difficult to pull together a TRL strategy. Moreover, as retailing becomes more complex and challenging, other business developments may well be regarded as a more pressing priority. The key is ensuring that the overall value of adopting this approach is measured and communicated with senior management teams.

Those companies that have embarked on a TRL journey have identified 12 key issues to consider:

1) Get the C-suite Onboard: Like most significant change initiatives, senior management support is key – generating urgency, facilitating financial support and ensuring compliance – all are important in making a TRL-based strategy a success.

2) Develop a Business Case – Focus on the Size of the Prize: Making use of the available data and the organization’s appetite for change, build a strong business case that focusses on the financial benefits that might accrue from adopting a TRL-based approach.

3) Adopt an Incrementalistic Approach to TRL: The TRL typology should be viewed as a palette of possibilities that can be tailored to any given organizational context – start small and build gradually – it is very easy to take on more than is realistically manageable in the first instance.

4) Identify Quick Wins First: At the beginning, only focus on those areas of loss that are likely to generate successful outcomes and are readily deliverable – do not attempt too much too soon.

5) Organize for Utilizing TRL: Think about who will be accountable for delivering a TRL-driven approach, what resources might be required (particularly analytical) and how to leverage support from across the business.

6) Advocate for TRL – Act as Agents of Change: Pooling responsibility for the management of all the areas of loss covered in TRL is less than desirable. Ensure that those driving TRL act as ‘agents of change’ – collecting the data, prioritizing the work, and then recommending ameliorative actions to those best placed to deliver them.

7) Review Reporting Structures for TRL: While there is little standardization on lines of reporting across the loss prevention industry, given the breadth and scope of TRL, a number of respondents to this research argued strongly that the Finance function is best placed to provide overall co-ordination.

8) Prepare for Organizational Antagonism: The way in which TRL often cuts across a wide range of organizational responsibilities can cause the potential for functional disquiet based upon a perceived ‘land grab’ by those driving the TRL agenda. It is important, therefore, that an assessment of the likely reaction of those impacted by a TRL initiative is undertaken, with a view to taking pre-emptive actions to explain, reassure and support.

9) Think About the ‘Right’ Name for your TRL: While the phrase Total Retail Loss has become relatively well known in the global loss prevention community, it is important that individual organizations develop their own label for their TRL-inspired initiative, based upon their particular circumstances and context. For a number of respondents, moving to ‘Profit Protection’ was regarded as a useful moniker that accurately described what the TRL-inspired initiative was aiming to achieve.

10) Avoid Terminological Confusion: It is important that as a business embarks on a TRL-oriented journey, the language that is used is clear and focused – by all means continue to use the term ‘shrinkage’ as a proxy for unknown stock loss, but ensure that there is a clear distinction made between that and the broader loss picture that you are aiming to develop.

11) Use TRL as an Analytical Lens: As well as providing a broad ranging and overarching framework for assessing and managing retail losses, the TRL concept can also be used in a much more focused way to evaluate the likely impact of any planned innovation and change by a business. By stimulating a more comprehensive assessment of the likely impact across a broad palette of losses, the TRL model can enable a more realistic and balanced ROI to be calculated for any given innovation or retail change.

12) Remember Timing is Key: Finally, like most decisions in life and work, timing can play a huge factor in dictating the success or not of any given initiative. Reflect upon the current organizational climate and whether it is likely to be broadly receptive or not to the introduction of a TRL-based approach. Where the head winds are deemed to be too strong, and other priorities too dominant, then delay may well be right approach.

Recent research found that companies that were engaging with TRL did so for the following reasons: provided a better framework to capture all forms of retail losses; created opportunities to positively impact on business profitability; helped to ensure resources were more effectively targeted; enabled the loss prevention function to maintain relevance; created greater transparency and accountability; and helped to manage increasingly complex retail environments.

The TRL concept is designed to be flexible, capable of changing as the retail risk profile changes, along with retailers’ capacity to measure it. As such the first version of the TRL typology published in 2016 included 33 categories of loss, while the second version, published in 2018, had 42 categories. Although the concept suggests it covers all forms of loss, ‘Total’ Retail Loss, is in fact based upon only those categories of loss which are described as being Manageably Measurable and Meaningful to the retail utilising it. To review the current range of categories of loss included in the typology, visit the Total Retail Loss research pages elsewhere on this website.

The TRL concept is designed to be flexible, capable of changing as the retail risk profile changes, along with retailers’ capacity to measure it. As such the first version of the TRL typology published in 2016 included 33 categories of loss, while the second version, published in 2018, had 42 categories. Although the concept suggests it covers all forms of loss, ‘Total’ Retail Loss, is in fact based upon only those categories of loss which are described as being Manageably Measurable and Meaningful to the retail utilising it. To review the current range of categories of loss included in the typology, click here to visit the Total Retail Loss research or click here to view the latest blogs on Total Retail Loss.

Probably the biggest difference with other measures of retail loss is the breadth and depth of the loss categories included in the TRL typology. It now includes 42 categories of loss broken down into four areas: retail stores; the retail supply chain; E-commerce activities and corporate. It then breaks these into categories where the cause of the loss is either known or unknown and then where the cause is known, it differentiates between those that are regarded as malicious or non-malicious in nature. As such, it is regarded as the most comprehensive and well-defined approach to understanding the cost of retail losses to date.

A recent review of how retailers are using TRL showed that few if any have yet to embrace an approach which commits to using all of these categories in their loss prevention strategy. Even the 10% of companies that declared they had ‘fully embraced the concept’ were far from populating all of the categories with a value of loss.

What is much more evident is a tailored approach to using this typology – companies reflecting upon their current capabilities, priorities, resource availability, organisational culture and appetite for change, and then creating their own, often more limited version of the TRL typology. They are selecting and, in some cases, adding categories of loss that work best for them in the current circumstances in which they find themselves. It is an approach that is eminently sensible – using the TRL typology as an adaptable resource and not an ideological straitjacket – something which can be used to trigger a broadening of understanding, taking an organisation beyond the moribund strictures of only thinking about loss as a function of unknown stock loss/shrinkage.

Consensus is actually very hard to find on what the term ‘shrink’ or ‘shrinkage’ means and what should be included and excluded when it is being calculated. Some authors regard it as a catch all for a wide range of losses suffered by retailers, including both crime-related events such as staff and customer theft, and errors incurred as part of the process of retailing, such as incorrect pricing, changes in price, damaged products and food items going out of date, while others only seem to use it to refer to variance in the value of expected and actual inventory.

Most of the published surveys and reports on shrinkage typically break it down into four areas of loss: employee/internal theft; customer/external theft; administrative/paperwork error; and vendor/supplier fraud. These categories, and the associated guesstimates of their significance, have dominated the reporting of shrinkage for decades. While the first two: internal and external theft, can be readily understood and defined, the latter two are much more difficult to categories. As detailed above, administrative error is a catch all phrase that can include a wide range of retail costs, while vendor supplier fraud is a notoriously difficult category to try and identify and measure with any precision. While there is a simple elegance to these four categories of loss, it is questionable whether they are still appropriate/useful in 21st Century retailing, particularly with the rise of online shopping and other retail developments.

The origins of the word ‘shrinkage’ seems to have been traced back to the UK Co-operative Movement in the 1860s and from there it began to be adopted in other countries as a term to describe the difference between expected and actual retail sales, based upon a valuation of delivered inventory compared with actual inventory in the business. Other writers refer to ‘shortages’, ‘inventory shrink’, ‘inventory shortage’, ‘retail inventory loss’, or simply ‘loss’ rather than ‘shrinkage’ although they all seem to be essentially trying to describe the same sort of thing. So, it is a longstanding and enduring term used to describe a varying basket of retail losses.

Probably yes, but it is often very unclear from the existing definitions and descriptions of shrinkage the extent to which both known losses, where the cause of the loss is apparent, and unknown losses, where no clear identifiable cause can be identified, are included. It would seem that virtually all published definitions and calculations rely heavily upon the difference between expected and actual stock levels/values, which, depending upon when the stock audit took place, will rarely if ever provide any meaningful understanding as to the root causes of the loss. In some circumstances, the loss could have occurred almost a year ago – did the missing item ever arrive, was it thrown away but not recorded as such, did a member of staff steal it, was it taken by a customer, did a member of staff not scan the item at the checkout? The possible reasons for the loss are many and varied but what is usually very clear is that the cause of loss is unknown and remains so despite the best intentions of those who may be tasked to speculate about possible reasons.

But, as can be seen above, agreeing if and what potentially known losses could be included in a shrinkage definition is not clear cut and some of the words and phrases used (administrative errors, process failures etc.) are at best vague catch all terms which could incorporate (or not) a varied list of possible losses which, depending upon the type of retailer, could significantly impact upon the size of the overall shrinkage number. However, for the most part, and for most retailers, the term shrink or shrinkage is largely used to describe those losses where there is no apparent evidence as to WHY the loss occurred – the reason is not clear and therefore they should be correctly described as losses where the cause is unknown.

Advocates of the Total Retail Loss concept would argue that due to ongoing and irrevocable variances in how the term shrink or shrinkage is defined and used by retail businesses around the world, and the significant changes in the way in which retailing now operates, it is a term no longer fit for purpose, or at the very least should be replaced with the term ‘unknown stock loss’ as this better describes what it is typically measuring. However, it is a term with a long history and therefore it is likely to be used for a long time to come.

When it comes to defining shrink or shrinkage there is much variance and little agreement within the world of retailing. For instance, some researchers describe it as ‘the difference between book inventory (what the records reflect we have) and actual physical inventory as determined by the process of taking one’s inventory of goods on hand (what we count and know we actually have)’.

However, another author defines it more specifically as ‘the amount of merchandise that disappears due to internal theft, shoplifting, damage, mis-weighing or mis-measuring and paperwork errors’, while another researcher focuses more on the value of goods and considers it to be ‘the disparity between the financial value of stock acquired and sold and the financial value of stock left on the shelves’. Yet another writer offers more detail by attempting to define the elements that are non-crime, such as ‘error’, which is regarded as ‘a result of inaccurate decisions or failures’ which include mispricing goods, not accounting for them properly, not reclaiming effectively from suppliers and under/over delivery of merchandise with the wrong specification. This writer also talks about ‘processing losses’, which are instances where it may be ‘impossible to sell every item of inventory at the authorized price’, and ‘waste’ (price reductions due to product deterioration and damage) being part of shrinkage. Together these non-crime losses are grouped together under the general heading of administrative/internal error.

Finally, some researchers have developed probably the broadest definition of shrinkage to date: ‘intended sales income that was not and cannot be realized’, looking at the issue primarily as one focused on the lost profit opportunity of the merchandise brought in to a retail business. They view any loss in the intended profit (however that may be calculated) as a loss to the business, although they tend to rely upon what has been described as the ‘four buckets of shrinkage’ to categorise their losses (see below).

So, as can be seen, there is little or no general agreement on how the term shrink or shrinkage should be defined beyond a general sense that it is largely measuring the difference between the volume or value of stock that a retailer thinks they have and what they actually have.

The inadequacies of the existing and widely used term shrink or shrinkage can be found elsewhere in this Q&A section of the website. Generally speaking, the advocates of the TRL concept argue that the incredible growth in the complexity of retailing, combined with a vastly more broad ranging risk landscape and capacity to better measure and understand that landscape, increasingly means that the rather one-dimensional measure of loss offered by the term shrink or shrinkage, is simply no longer fit for purpose or sufficient to enable retail businesses to respond to, and manage, the losses that negatively affect profitability and the customer experience.

How you put a value on shrinkage also generates a significant amount of variance within the retail community, although most shrinkage surveys are explicit in requesting that data be provided at retail prices, calculated as a percentage of sales turnover. Some authors suggest that the majority of retailers calculate their shrinkage at retail prices, with between 20% and 40% using cost price or a combination of cost and retail prices. Using retail value typically generates a much bigger shrinkage number, which can be useful for drawing attention to the problem (internally and externally), and factors in the potential impact of loss on retail margin, as well as compensating for some of the consequential costs of shrinkage (additional transportation, staff time etc.). However, it can generate a misleading number – changes to the retail price can mask known shrinkage problems (such as the impact of price increases on the value of current and previous stock holdings), or the difficulty of calculating the retail price of a product in a sector that is highly driven by sales and discounting.

Total Retail Loss (TRL) is a concept that adopts a broad ranging and inclusive approach to understanding and categorising all the manageably measurable forms of loss that a retail business might experience across the entire organisation. Based upon years of research, it was coined by the academic Professor Adrian Beck and originally published in a series of research reports published both by the ECR Retail Loss Group and the Retail Industry Leaders Association in the US in 2016. It sets out a clear definition of what is meant by the term ‘retail loss’: Events and outcomes that negatively impact retail profitability and make no positive, identifiable and intrinsic contribution to generating income. It contrasts this with what are regarded as retail costs: Expenditure on activities and investments that are considered to make some form of recognizable contribution to generating current or future retail income. In addition, it identifies a subset of retail costs called ‘margin eroders’, which have often been included by some in their definition of shrink or shrinkage: planned and unplanned activities and behaviours which, strictly speaking, negatively impact upon overall retail profitability, but nevertheless, can be seen as having a beneficial role to play in helping the business generate current and future profits.

It is important to note that TRL is primarily designed to enable the ‘value’ of retail losses to be calculated and not necessarily the number of events – where an associated ‘value’ cannot be calculated or there is no loss of value associated with an incident, this is not included. For instance, if a shoplifter is apprehended leaving a retail store and the goods they were attempting to steal are successfully recovered and can be sold at full value at a later date, there is no financial loss associated with this incident. That is not to say that the retailer may still want to record the fact that an attempted theft took place and was successfully dealt with, but that it would not be recorded in the TRL concept. In this respect TRL is exclusively focused upon recording the value of retail losses and not their prevalence.

Beyond an ongoing lack of agreement about an industry-wide definition for shrink or shrinkage, which makes efforts at benchmarking deeply flawed, critics of the term argue that three major changes in the world of retailing mean that it is increasingly an unsatisfactory way to understand and describe the losses experienced by retailers. The first is the growing complexity of the retail industry – when the term was first used in the 1860s, retailing was a relatively simple process – counter-based service with little consumer interaction with the product. Fast forward 150 years of more and retailing is a profoundly different business – online, self-selection, self-scan, vast and complex supply chains to name but a few of the changes. Secondly, the range of risks faced by retailers has changed dramatically since the term shrink or shrinkage was first used – theft of products by customers is now but one of a welter of issues that retailers have to manage, such as fraud, violence, counterfeit, product contamination, cash loss, margin erosion, to name but a few. Finally, retailers now have a much wider and deeper pool of business data to draw upon to understand how a range of losses are affecting their organisation than when the term shrink or shrinkage was first coined. So, taken together, the incredible growth in the complexity of retailing, combined with a vastly more broad ranging risk landscape and capacity to better measure and understand that landscape, increasingly means that the rather one-dimensional measure of loss offered by the term shrink or shrinkage, is seen by some as no longer fit for purpose.

The retail sector is not short of surveys trying to ascertain the scale and nature of the shrinkage problem it faces. In the US there is the longstanding National Retail Security Survey, while more globally there has been various sweeps of the Global Retail Theft Barometer, covering a varying number of countries. In addition, many surveys have been undertaken over the years covering particular retail sectors and a range of different countries. Virtually all of these surveys rely upon respondents providing a ‘shrinkage’ figure with varying degrees of explanation about what should be included and excluded from this number. For instance, in the past the National Retail Security Survey (NRSS) asked for: ‘your firms fiscal inventory shrinkage (excluding damages and spoilage)’, while the 2008 version of the Global Retail Theft Barometer asked for the ‘Corporation’s shrinkage or stockloss for 2007-2008 financial year (or most recent year) as a percentage of turnover)’. It then goes on to ask a further question about whether wastage/or spoilage was included in this figure and if it was to provide this, presumably as a percentage of turnover (although it is not clear). Both surveys then request that the respondent provide a best guess or estimate of the likely causes of this unknown loss using the typical four buckets of shrinkage outlined above, although for the NRSS, the category of ‘Administrative and paperwork error’ obviously now excludes damages and spoilage, and there is also an option for respondents to choose ‘unknown loss’ as an explanation of their unknown loss!

As detailed above, given that most definitions of shrinkage are based upon data derived from variance in expected and actual stock holding, the data is almost always a measure of unknown loss. From these estimates the surveys then calculate the apparent causes of loss, with some carefully tracking and micro analyzing annual changes and differences between countries and retails sectors based upon this data. Some authors have been highly critical of this approach. One said: Attributing known losses to these [loss] classifications is fairly straightforward. The problem arises with the inclination of business and academia to apportion a value for total shrinkage, i.e. known and unknown shrinkage, to these categories. Instead of an honest answer along the lines of: Retailing is a complex business, there are many mechanisms through which shrinkage can occur and we don’t know which ones apply in this instance, there is a tendency to use judgement/estimation/guess work to apportion unknown shrinkage to each category. Despite the fundamental weakness, this erratic approach is the default mechanism all too often used to inform management thinking and direct investments in loss prevention solutions when faced by a lack of hard data.

Others have highlighted similar problems: [the data] can only been seen as a measurement of how respondents currently feel about each of the factors they are requested to make estimations about – they are socially constructed and more than likely a distorted picture of the problem based upon personal prejudice.

Without doubt, some of these surveys have played an important role in helping the loss prevention industry understand how it is thinking about the problem of loss. Other parts of these surveys, which for instance, focus upon the extent of the use of various approaches to managing loss, have been important in providing benchmark data. But the rapidly changing retail landscape, together with the way in which retailing is not only experiencing a broader range of losses, but is also growing its capacity to collect and analyze data on them, would suggest that a new approach to benchmarking retail losses may well now be required.

Introduced in the 1970's, originally in lending libraries to stop the theft of books, EAS has evolved and is now considered the technology that offers the very first line of defence against shop theft and with the exception of the supermarkets channel, EAS pedestals can be found at the exit and entrance of most hypermarkets, home improvement retailers, drug stores, apparel and fashion stores, department stores and specialty such as Auto-parts.

In terms of technology, in the first instance came Electro Magnetic tags, these were strips of metal that neatly sat inside books. Today, only two EAS technologies are present, Acousto Magnetic (AM), and Radio Frequency (RF). Each has their advantages and disadvantages, with each retailer making their own decisions. In the US for example, Walmart chose AM, Target chose RF. In the UK, Boots chose AM, Tesco chose RF. In some countries, and channels, for example French grocery retailers, the majority, if not all, chose RF.

EAS can be applied at the source of production (source tagging) or in the store. When applying at the source, soft tags are preferred as they are easier and simpler to apply to bottles, health & beauty products, meat, etc. Soft tags are disposable and will go home with the shopper [deactivated]

On the other hand, hard tags (for bottles, attached to safer cases, for clothes, etc) are more pre-disposed to a local application given their size and the need to recycle this more expensive hard tag. However, the apparel retail sector have identified a recycling programme, whereby hard tags are applied in the garment factories, shipped to stores and then returned to the garment factories.

One final step in the evolution of EAS has been the recognition of its limitations, and the industry is becoming much clearer that EAS is primarily aimed for, and most successful at deterring the opportunist thief, as opposed to the so called professional thief stealing for resale. To this end, when the industry thinks about soft tags, and source tagging, it has turned its attention to carrying messages on products that have EAS protection, that signal to the opportunist that these products have a security tag included.

EAS is a means by which retailers can determine whether an item leaving a store has been paid for or not. If the item has been paid for, then either the soft EAS tag would have been deactivated at the point of sales by the scanner, or the hard tag, sometimes included in a safer case box, will have been removed. If the item has not been paid for [and deactivated] or hard tag removed, then the pedestals at the exit will emit an alarm that will draw the attention of store associates and store guards who can assist the customer and identify the items not paid for / causing the pedestals to alarm.

Main office

ECR Community a.s.b.l

Upcoming Meetings

Join Our Mailing List

Subscribe© 2023 ECR Retails Loss. All Rights Reserved|Privacy Policy

.jpg?ixlib=gatsbyFP&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=max&w=960&h=960)