Beyond Shrinkage: Introducing Total Retail Loss

Table of Contents:

- Abstract

- Foreword

- Executive Summary

- Background and Context

- Methodology

- The Changing Retail Landscape

- Making (No) Sense of Shrinkage

- - Defining Shrinkage

- - The ‘Four Buckets’ of Shrinkage

- - Known and Unknown Shrinkage

- - The Location of Shrinkage

- - The Measurement of Shrinkage

- - Shrinkage Surveys

- The Parameters of Total Retail Loss

- - Differentiating Between Retail Costs and Retail Losses

- - Defining Total Retail Loss

- - Margin Eroders – Cost or Loss?

- - Categorizing Total Retail Loss

- - The Total Retail Loss Typology

- - Categories of Store Losses

- - Categorizing Retail Supply Chain Losses

- - Categories of E-Commerce Losses

- Putting a Value on Total Retail Loss

- Using the Total Retail Loss Typology

- - Helping Your Business Make Good Choices

- - Benchmark or Business Tool?

- - Developing the Role of Loss Prevention in the Future

- Next Steps

- Appendix

- - Total Retail Loss Scorecard

- - References

- - The Total Retail Loss Typology

Languages :

This report, which was first published in 2016, and introduced the concept of Total Retail Loss, focussed upon understanding how the retail industry understood the nature and extent of all the potential types of losses they experience, as well as publishing a definition of ‘loss’ and associated typology. It is based upon a detailed literature review together with an online survey of retailers and 100 interviews with senior retail executives in the US.

The report put forward the original definition of ‘Total Retail Loss’ (TRL) together with a typology made up of 33 categories of loss that covered the entire retail environment, from shop theft in physical retail stores to frauds in corporate headquarters. It provided a unique way of thinking about how a much broader range of losses impact upon retail businesses, differentiating between the ‘costs’ of being a retailer and the ‘losses’ that negatively impact business profitability. In addition, the report offers detailed definitions of each of the categories of loss with a view to improving the accuracy of future benchmarking exercises.

The study went on to suggest that by using TRL, retail businesses in general, and loss prevention practitioners in particular, will be able to not only better understand the impact of current and future retail risks, but also make more informed choices about the utilisation of increasingly scarce resources. For loss prevention specialists, the report asserts that it provides a unique opportunity to build upon and reinforce the critical role they can play in becoming agents of change within their retail businesses.

This report should be read in conjunction with a follow up study, published in 2018, which provides a more up-to-date Total Retail Loss Typology, as well as summarising the experiences and lessons that can be learnt from retailers that have begun to use this approach.

Abstract

This report, which was first published in 2016, and introduced the concept of Total Retail Loss, focussed upon understanding how the retail industry understood the nature and extent of all the potential types of losses they experience, as well as publishing a definition of ‘loss’ and associated typology. It is based upon a detailed literature review together with an online survey of retailers and 100 interviews with senior retail executives in the US.

The report put forward the original definition of ‘Total Retail Loss’ (TRL) together with a typology made up of 33 categories of loss that covered the entire retail environment, from shop theft in physical retail stores to frauds in corporate headquarters. It provided a unique way of thinking about how a much broader range of losses impact upon retail businesses, differentiating between the ‘costs’ of being a retailer and the ‘losses’ that negatively impact business profitability. In addition, the report offers detailed definitions of each of the categories of loss with a view to improving the accuracy of future benchmarking exercises.

The study went on to suggest that by using TRL, retail businesses in general, and loss prevention practitioners in particular, will be able to not only better understand the impact of current and future retail risks, but also make more informed choices about the utilisation of increasingly scarce resources. For loss prevention specialists, the report asserts that it provides a unique opportunity to build upon and reinforce the critical role they can play in becoming agents of change within their retail businesses.

This report should be read in conjunction with a follow up study, published in 2018, which provides a more up-to-date Total Retail Loss Typology, as well as summarising the experiences and lessons that can be learnt from retailers that have begun to use this approach.

Disclaimer

This report has been compiled for the Retail Industry Leaders Association, USA. The document is intended for general information only and is based upon an extensive review of the available literature together with primary research undertaken with retail companies in Europe and the USA. Companies or individuals following any actions described herein do so entirely at their own risk and are advised to take professional advice regarding their specific needs and requirements prior to taking any actions resulting from anything contained in this report. Companies are responsible for assuring themselves that they comply with all relevant laws and regulations including those relating to intellectual property rights, data protection and competition laws or regulations.

© August 2016, all rights reserved.

Foreword

This unique and timely study, commissioned by the RILA Asset Protection Leaders Council, is the latest in a series of strategic research projects designed to bring new insights, tools, and techniques to help the industry better understand and tackle the problem of retail loss.

Carried out by Professor Adrian Beck from the University of Leicester in the UK, this study set out to provide the retail industry with a better understanding of what constitutes retail ‘loss’, moving beyond the traditional confines of ’shrinkage’, to develop the much broader concept of ’Total Retail Loss’. Based upon interviews with 100 senior retail executives in some of the largest US retailers, the research offers fresh thinking on how retailers not only might define and measure retail losses, but also the potential future role of loss prevention practitioners and how they can continue to deliver value to their businesses.

RILA would like to thank Professor Beck for his thought leadership as well as Checkpoint Systems and Ernst & Young for their support and commitment to helping retailers achieve operational excellence. We would also like to recognize the valuable support offered by the ECR Community Shrinkage and On-shelf Availability Group, and finally, we thank the many retailers that participated in the study.

Lisa LaBruno

Senior Vice President

Retail Operations Retail Industry Leaders Association (RILA)

Executive Summary

While the word ‘shrinkage’ or ‘shortage’ has been in use for more than a 100 years to describe retail ‘losses’, it does not enjoy a universally agreed upon definition in terms of what is included and excluded when it is used, nor how the value of losses should be calculated. Often used to describe the difference between anticipated and actual levels of retail inventory, where the root causes of losses are typically unknown, it has become a catch all term used by the industry to describe a wide variety of retail-related losses, some of which relate as much to lost margin as they do lost stock.

This lack of a universally agreed definition has led to existing industry surveys on shrinkage generating data which can be highly problematic to benchmark against, especially when it is unclear what types of loss have been included or excluded by respondents.

Moreover, retailing is now able to generate a broader range of data points across the entire value chain – gone are the days when differences in anticipated and actual store stock levels were the only data game in town – new sources of data are now available to better understand how a broader range of losses are impacting upon retail businesses.

Given all of this the Retail Leaders Industry Association’s Asset Protection Leaders Council, commissioned research to look at how the retail industry currently understands the nature and extent of all the potential types of losses they presently experience, with a view to developing a new definition of loss and associated typology fit for the 21st Century retailing landscape.

This report puts forward a new definition of ‘Total Retail Loss’ together with a typology made up of 33 categories of loss that span the entire retail environment, from shop theft in physical retail stores to frauds in corporate headquarters. It offers a unique way of thinking about how a much broader range of losses impact upon retail businesses, differentiating between the ‘costs’ of being a retailer and the ‘losses’ that negatively impact business profitability. In addition, the report offers detailed definitions of each of the categories of loss with a view to improving the accuracy of future benchmarking exercises.

It is believed that by using Total Retail Loss, retail businesses in general, and loss prevention practitioners in particular, will be able to not only better understand the impact of current and future retail risks, but also make more informed choices about the utilization of increasingly scarce resources.

For loss prevention specialists, it provides a unique opportunity to build upon and reinforce the critical role they can play in becoming agents of change within their retail businesses.

Background and Context

There is little consensus on what constitutes ‘loss’ within the retail world nor how it should be measured. The terms ‘shrinkage’ and ‘shortage’ have been loosely applied to encapsulate some of the areas that generate loss but they are not terms enjoying a clear and agreed upon definition across the sector. Equally, measuring losses at retail prices is probably the most common method adopted to capture the scale of the problem, but again, it is not without its critics – some suggesting it overstates the problem while others believe it does not sufficiently capture all the consequential costs of products being lost, damaged, stolen or going out of date. It can also be an unreliable indicator of risk, frequently not taking account of the profit margin associated with a particular product or indeed allowing for variations in how products are valued at any given time. Moreover, while the term ‘shrinkage’ has been used for probably the last 100 years of retailing, there continues to be wide variance on what is included and excluded when this term is used, with some retailers using it to describe only those losses captured through identified discrepancies in inventory counts, while others add in additional types of loss recognized through other forms of recording practices.

The inclusion or exclusion of losses associated with the retailing of items such as food adds further ambiguity – should products that have been recorded as going out of date be included as shrinkage; what about those items that have been reduced in price to encourage a sale due to oversupply or a change in consumer demand, or products that have been damaged in the supply chain? Even more variability exists when the losses associated with what are sometimes called ‘process failures’ are considered – should those losses that are generated by mistakes within the business be included in the overall shrinkage figure, such as product set up errors, non-scanning at the till by members of staff, the reduction in sales caused by products being out of stock or shelves not being replenished accurately? Moreover, there is increasingly a tranche of losses that can be associated with discrete and purposeful decisions made by retail organizations as part of pledges and guarantees to consumers – price matching, compensation for poor service and guarantees of product availability – should these be included in a definition of retail loss? Finally, the growing breadth and complexity of the retail landscape is putting stress upon the applicability of traditional shrinkage definitions – how might losses associated with on line and so called Omni-channel retailing be measured and understood?

Given all of this, perhaps it is not surprising that some have begun to argue that the term ‘shrinkage’ is no longer fit for purpose either as an accurate descriptor of loss nor as a means of retail businesses benchmarking themselves against others. When one organization includes a broad range of process-failure related measures but another excludes them from their definition, how can any meaningful comparison be drawn between the overall loss values provided by each business? In addition, if retail businesses are to have any genuine impact upon the problem of retail losses, then the management of loss prevention needs to be the responsibility of a broader range of business units, such as Store Operations, Supply Chain, IT, and Store Management teams. However, persuading multiple business functions to engage with the issue of ‘shrinkage’ or retail loss is not easy – its historical association with, and seeming prioritization of, crimerelated problems, can act as a powerful disincentive to get involved. This has led some to consider abandoning the term ‘shrinkage’ in favor of Total Retail Loss – the latter perhaps being viewed as more appealing to a broader range of functions as it intends to cover a greater range of activities that impact directly upon business profitability.

An additional by-product of this growing lack of clarity around how the losses experienced by retailers are measured and understood is that those traditionally tasked with managing the loss problem – ‘loss prevention teams’ – are becoming more unsure about what should be regarded as within their remit of responsibility – do they continue to only focus on malicious-oriented (crime-related) problems or should they begin to utilize their extensive problem solving skills to tackle other areas of loss within retail businesses, especially when increasingly sophisticated data streams enable other areas of loss to be more readily identified?

It is within this context that the Retail Industry Leaders Association (RILA) commissioned a study to look at how the retail industry currently understands the nature and extent of all the potential types of losses they presently experience (however they might be defined), with a view to developing a new definition of loss and associated typology fit for the 21st Century retailing landscape.

The research presented in this report had four main objectives:

- Review the way in which retailers currently define and measure loss within their businesses.

- Develop a definition of Total Retail Loss that enables the industry to better understand the difference between outcomes and events considered to be the ‘costs’ of doing business, and those which can be regarded as ‘losses’.

- Identify, categorize and define the range of losses associated with a Total Retail Loss Typology, ensuring that they are manageably measurable and meaningful to as broad a range of retail environments as possible.

- Develop a method for systematically measuring the cost of retail losses that is consistent and applicable across differing retail contexts.

The following section of the report will outline the methodology adopted for this research before going on to briefly discuss the rapidly changing retail landscape within which this study is set. It will then go on to consider in detail some of the challenges current methods of measuring retail losses present, in particular the lack of consensus around what the term ‘shrinkage’ actually means and how its use varies considerably across the industry. The report will then go on to present the results from the research and offer a detailed explanation of what the components parts of a Total Retail Loss definition and typology might constitute. It will map out in detail the rationale for this approach, focusing particularly on how the difference between retail costs and retail losses can be better understood, how the industry needs to recognize the difference between losses and what can be described as ‘margin eroders’, and how a value can be put upon the various component parts of Total Retail Loss. Finally, the report will go on to consider why and how retailers might begin use the Typology in the future and summarize some key next steps for this work.

Methodology

The project utilized a number of different methodologies although given the overarching aims and objectives of the research, they were primarily qualitative. Initially, an extensive literature review was undertaken to understand how current definitions of loss and in particular the various terms relating to shrink and shortage, have evolved, been defined and used by academics and practitioners. This included reviewing academic journals and books as well as practitioner-focused publications such as the Loss Prevention Magazine and the Security Professional, and a wide range of sources available from the Internet. This was then followed by two interlinked phases of data gathering, initially utilizing an inductive approach focused upon allowing theory to emerge from a series of observations and interactions with senior representatives of retailers, manufacturers, industry consultants and companies providing support services to retailing. The research adopted a Grounded Theory approach focused upon using a set of rigorous research procedures that allowed the conceptual categories of retail loss to emerge as the research progressed. As such, no preconceived notions of what constitutes retail loss were initially put forward and instead respondents were offered the opportunity to describe how they viewed retail loss using their own words. Later stages of the research then enabled a more deductive approach to be adopted, which was focused more on beginning to test the emerging framework that had been developed from the earlier phases of the research.

Through links provided by the Retail Industry Leaders Association (RILA) and the ECR Community Shrinkage and On-shelf Availability Group, three main data collection methods were developed.

The first was based upon a questionnaire sent to a small selection of European retailers soliciting feedback on how they currently measured and understood a range of retail losses. All were current members of the ECR Community Shrinkage and On-shelf Availability Group. In total, five retailers responded to this initial scoping phase of the research; four were Grocers with the fifth focused primarily on health and beautyrelated products. The companies had a combined retail turnover of $179 billion.

The second data collection method was based upon a series of interviews with senior directors in a number of the largest retailers in the US, representing a range of different business functions. The retailers were selfselecting based upon an email sent to Heads of Loss Prevention via RILA’s Asset Protection Leaders Council, requesting their support and help. Of those contacted, 10 companies agreed to participate covering a range of types of retailing, including: Grocery; Home Improvement; Pharmacy; Department Store; Art and Crafts; Sporting Goods; and Auto Parts. In total, these companies represented annual sales in excess of $859.6 billion or 27% of the total US retail market.

It was important to solicit views from executives beyond just the traditional Loss Prevention function as it was thought that a wide range of types of loss might be found across retail companies. Therefore, interviews were held with exactly 100 executives covering the following functions (the precise name of the function varied slightly between retailers): Loss Prevention; Internal Audit, Accounting/Finance, Supply Chain; Risk Management; Store Operations; Merchandising; Omni Channel; Product Development; Stock Controllers; Analytics; Information Services; Organized Retail Crime; and Safety. Most of those interviewed were at either Vice President or Executive Vice President Level together with a number of function Directors and subject-specific specialists. Some of the interviews were one-to-one while others were done in small groups, with the average interview time being approximately 50 minutes. Respondents were sent a list of questions in advance and these were used to guide the interviews although opportunities were provided throughout for them to explore issues of loss as they understood the term from their perspective and business function. All interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed for analysis. In total, some 52 hours of interviews were collected as part of this phase of the research.

The final data collection method was based upon a series of workshops and focus groups with loss prevention representatives from a range of European retailers and manufacturers that are members of the ECR Community Shrinkage and On-shelf Availability Group. These sessions took place over an 8-month period and lasted on average two hours with the number of representatives ranging between 15 and 40. In total, 4 sessions were held and on each occasion, delegates were provided with an overview of the research findings to date, together with an opportunity to consider a number of research questions, including: applicability of emerging loss definitions and overarching framework, the feasibility of data collection, and the potential impact of the evolving loss typology on organizational structure and problem ownership. Detailed notes were taken at each of these sessions and were used as part of the inductive and deductive process.

Once a draft Total Retail Loss typology had been developed, together with a series of definitions for each of the components parts of the model, feedback was solicited from each of the US companies that had participated, members of the ECR Community Shrinkage and On-shelf Availability Group, and other retailers and industry experts who were known to the researcher. This was done via a detailed research document that requested feedback on the following areas: the definition of Total Retail Loss; how to put a value on Total Retail Loss; measuring, locating and categorizing retail losses; the proposed typology of retail loss; and the underlying definitions for the proposed categories of loss.

Notes of Caution

Whenever a research project employs qualitative methods questions arise about the representativeness of the information that has been collected. By using both RILA and the ECR Community Shrinkage and On-shelf Availability Group the choice of participating retailers was clearly limited to those who were members of these groups. These are typically large retailers and, in the case of the ECR Community Group, predominately Grocers. Therefore, the views of smaller retailers are largely absent from this research as are the views of some specialist retail companies and businesses not operating in the US and Europe. As with any research on commercial organizations, access is always problematic for researchers – they are wholly reliant upon those companies that are willing to participate and their views will inevitably feature prominently in the final analysis. However, by utilizing retailers from across both the US and Europe and ensuring a number of different data collection approaches, together with an opportunity for feedback from a broader cohort of companies, it is hoped that the results are largely representative of a reasonable range of retailers. In addition, given the relative complexity of the potential data collection process necessary should a retailer seek to utilize the proposed Total Retail Loss typology, it is highly likely that only larger, better resourced companies will engage with this framework in the first instance. It is therefore considered appropriate that their views should play a large part in the formulation of the proposed typology.

The Changing Retail Landscape

Probably the one constant that can be relied upon in retailing is change – it a highly dynamic, complex and fast moving sector of the economy where reinvention, innovation and adaptation are cornerstones for continuing success. In many respects, while the 20th Century saw remarkable changes in the way in which retailing was both perceived and organized, the 21st Century has seen the pace of change increase at an even greater rate, with new technologies being introduced, an increasingly demanding customer base developing and a broader more complex economic environment evolving. Back in the late 19th Century when the term ‘shrinkage’ was first beginning to be used to describe unexplained losses, retailing was a much simpler place – most if not all goods were stored behind a counter with customer access strictly controlled and regulated. Shopping was regarded by most consumers as something that had to be done to acquire the goods necessary for day-to-day living, rather than how it is viewed today – an end in itself, a pleasurably and absorbing pastime firmly embedded in the social and cultural makeup of most developed countries.

In many respects, the growth of retailing throughout the 20th Century, and the consumerism that underpins it, is one of the great success stories of the global economic system. While the trade of goods between nations is nothing new, the importance of retailing, economically, politically and perhaps most importantly, culturally is profound. With that comes a scale and complexity which is extraordinary and at times mind boggling. For example, if the 10 US companies taking part in this research were a country, and their turnover represented Gross Domestic Product (GDP), then they would be ranked 17th in the world, ahead of Saudi Arabia, Switzerland and Sweden. Globally, retail sales amount to more than $22 trillion a year, dwarfing the GDP of the largest country, the USA.

Of course long gone are the days when all products were held behind a counter away from the inquisitive fingers of consumers and where range and availability were dictated by the retailer. Now the consumer is front and center, demanding more choice, more availability, faster access and offering far less loyalty in return. The growth of on online shopping in some markets has added a new dimension, with the highly savvy consumer being increasingly armed with market knowledge, prepared to shop around to get the best deal, frequently using the physical store more as a showroom or pick up point than a place of purchase. The constant desire to ‘please’ the consumer has seen the introduction of a welter of technologies and offers – self-scan checkouts, buy online pick up in store, mobile scanning, multi-buy offers, buy one get one free (BOGOF) deals, price matching, customer guarantees and so on. The pace of change and innovation is relentless and for those working in the industry probably frightening and exciting in equal proportion.

Yet throughout all of this dramatic and profound change in retailing over the last 100 years or more, the dominant measure for loss has remained pretty much the same – shrinkage – the term typically used to describe the difference between the stock a retailer thought they had and what they actually counted/ valued in their physical locations.

Making (No) Sense of Shrinkage

Consensus is actually very hard to find on what the term ‘shrinkage’ means and what should be included and excluded when it is being calculated. Some authors regard it as a catch all for a wide range of losses suffered by retailers, including both crime-related events such as staff and customer theft, and errors incurred as part of the process of retailing, such as incorrect pricing, changes in price, damaged products and food items going out of date, while others only seem to use it to refer to variance in the value of expected and actual inventory. The origins of the word ‘shrinkage’ seems to have been traced back to the UK Co-operative Movement in the 1860s and from there it began to be adopted in other countries as a term to describe the difference between expected and actual retail sales, based upon a valuation of delivered inventory compared with actual inventory in the business. Other writers refer to ‘shortages’, ‘inventory shrink’, ‘inventory shortage’, ‘retail inventory loss’, or simply ‘loss’ rather than ‘shrinkage’ although they all seem to be essentially trying to describe the same sort of thing.

Defining Shrinkage

When it comes to defining what is actually meant by these terms, there is much variance. For instance, Sennewald and Christman describe it as ‘the difference between book inventory (what the records reflect we have) and actual physical inventory as determined by the process of taking one’s inventory of goods on hand (what we count and know we actually have)’. Purpora defines it more specifically as ‘the amount of merchandise that disappears due to internal theft, shoplifting, damage, mis-weighing or mis-measuring and paperwork errors’, while Shapland focuses more on the value of goods and considers it to be ‘the disparity between the financial value of stock acquired and sold and the financial value of stock left on the shelves’.

Bamfield offers more detail by attempting to define the elements that are non-crime, such as ‘error’, which is regarded as ‘a result of inaccurate decisions or failures’ which include mispricing goods, not accounting for them properly, not reclaiming effectively from suppliers and under/over delivery of merchandise with the wrong specification. He also talks about ‘processing losses’, which are instances where it may be ‘impossible to sell every item of inventory at the authorized price’, and ‘waste’ (price reductions due to product deterioration and damage) being part of shrinkage. Together these non-crime losses are grouped together under the general heading of administrative/internal error.

Chapman and Templar have probably offered the broadest definition of shrinkage to date: ‘intended sales income that was not and cannot be realized’, looking at the issue primarily as one focused on the lost profit opportunity of the merchandise brought in to a retail business. They view any loss in the intended profit (however that may be calculated) as a loss to the business, although they tend to rely upon what has been described as the ‘four buckets of shrinkage’ to categorize their losses.

The ‘Four Buckets’ of Shrinkage

Most of the published surveys and reports on shrinkage typically break it down into four areas of loss: employee/internal theft; customer/external theft; administrative/paperwork error; and vendor/ supplier fraud. These categories, and the associated guesstimates of their significance, have dominated the reporting of shrinkage for decades. While the first two: internal and external theft, can be readily understood and defined, the latter two are much more difficult to categorize. As detailed earlier, administrative error is a catch all phrase that can include a wide range of retail costs, while vendor supplier fraud is a notoriously difficult category to try and identify and measure with any precision. While there is a simple elegance to these four categories of loss, it is questionable whether they are still appropriate/useful in 21st Century retailing, particularly with the rise of online shopping and other retail developments.

Known and Unknown Shrinkage

It is often very unclear from the existing definitions and descriptions of shrinkage the extent to which both known losses, where the cause of the loss is apparent, and unknown losses, where no clear identifiable cause can be identified, are included. It would seem that virtually all published definitions and calculations rely heavily upon the difference between expected and actual stock levels/values, which, depending upon when the stock audit took place, will rarely if ever provide any meaningful understanding as to the root causes of the loss. In some circumstances, the loss could have occurred almost a year ago – did the missing item ever arrive, was it thrown away but not recorded as such, did a member of staff steal it, was it taken by a customer, did a member of staff not scan the item at the checkout? The possible reasons for the loss are many and varied but what is usually very clear is that the cause of loss is unknown and remains so despite the best intentions of those who may be tasked to speculate about possible reasons.

Indeed, for some of the respondents to this research, their definition of shrinkage referred only to unknown loss – anything where the cause was known was regarded as something else and not included in the shrinkage ‘number’. As can be seen above, agreeing what known losses should be included in a shrinkage definition is not clear cut and some of the words and phrases used (administrative errors, process failures etc.) are at best vague catch all terms which could incorporate (or not) a varied list of possible losses which, depending upon the type of retailer, could significantly impact upon the size of the overall shrinkage number. For instance, two food retailers involved in this research took a very different perspective on what their shrinkage number included – for one it was only unknown losses, for the other it included unknown losses and a number of recorded known ‘process failures’, including what they described as Wastage and Damage. Given the nature of their business (food retailing), the inclusion of these ‘failures’ more than doubled the rate of shrinkage in the former company compared with the latter.

The Location of Shrinkage

Given the general reliance upon stock audits as the primary source of shrinkage data, perhaps it is not surprising that most discussions of shrinkage tend to be focused upon the traditional retail store – after all, this is where most audits are carried out. However, losses can occur throughout a retailers’ supply chain and while some companies do collect shrinkage data in their distribution centers, there is little consensus on the boundaries of a retail supply chain and what elements of loss within it would/should be included in a shrinkage calculation. This is becoming more important as ‘Omni channel’ retailing becomes even more widespread and the ‘location’ of the store and the shopper become much more fluid and uncertain. Most existing surveys on shrinkage still seem to focus just upon shrinkage in retail stores with little if any discussion about whether retailers have/ should included losses incurred elsewhere. Bamfield does refer to Supplier/distribution fraud as an area of loss in his versions of the Global Retail Theft Barometer survey although analysis of the questionnaire suggests that this is simply a category respondents can choose to explain their unknown store losses rather than an explicit question about specific losses measured/ recorded in the supply chain.

The Measurement of Shrinkage

How you put a value on shrinkage also generates a significant amount of variance within the retail community, although most shrinkage surveys are explicit in requesting that data be provided at retail prices, calculated as a percentage of sales turnover. Some authors suggest that the majority of retailers calculate their shrinkage at retail prices, with between 20% and 40% using cost price or a combination of cost and retail prices. Using retail value typically generates a much bigger shrinkage number, which can be useful for drawing attention to the problem (internally and externally), and factors in the potential impact of loss on retail margin, as well as compensating for some of the consequential costs of shrinkage (additional transportation, staff time etc.). However, it can generate a misleading number. For instance, some respondents to this research readily identified ways in which changes to the retail price could mask known shrinkage problems (such as the impact of price increases on the value of current and previous stock holdings), or the difficulty of calculating the retail price of a product in a sector that is highly driven by sales and discounting.

Shrinkage Surveys

The retail sector is not short of surveys trying to ascertain the scale and nature of the shrinkage problem it faces. In the US there is the longstanding National Retail Security Survey, while more globally there has been various sweeps of the Global Retail Theft Barometer, covering a varying number of countries. In addition, many surveys have been undertaken over the years covering particular retail sectors and a range of different countries. Virtually all of these surveys rely upon respondents providing a ‘shrinkage’ figure with varying degrees of explanation about what should be included and excluded from this number. For instance, the National Retail Security Survey (NRSS) asks for: ‘your firms fiscal inventory shrinkage (excluding damages and spoilage)’, while the 2008 version of the Global Retail Theft Barometer asked for the ‘Corporation’s shrinkage or stockloss for 2007-2008 financial year (or most recent year) as a percentage of turnover)’.

It then goes on to ask a further question about whether wastage/or spoilage was included in this figure and if it was to provide this, presumably as a percentage of turnover (although it is not clear). Both surveys then request that the respondent provide a best guess or estimate of the likely causes of this unknown loss using the typical four buckets of shrinkage outlined above, although for the NRSS, the category of ‘Administrative and paperwork error’ obviously now excludes damages and spoilage, and there is also an option for respondents to choose ‘unknown loss’ as an explanation of their unknown loss!

As detailed above, given that most definitions of shrinkage are based upon data derived from variance in expected and actual stock holding, the data is almost always a measure of unknown loss. From these estimates the surveys then calculate the apparent causes of loss, with some carefully tracking and micro analyzing annual changes and differences between countries and retails sectors based upon this data. Some authors have been highly critical of this approach:

Attributing known losses to these [loss] classifications is fairly straightforward. The problem arises with the inclination of business and academia to apportion a value for total shrinkage, i.e. known and unknown shrinkage, to these categories. Instead of an honest answer along the lines of: Retailing is a complex business, there are many mechanisms through which shrinkage can occur and we don’t know which ones apply in this instance, there is a tendency to use judgement/estimation/guess work to apportion unknown shrinkage to each category. Despite the fundamental weakness, this erratic approach is the default mechanism all too often used to inform management thinking and direct investments in loss prevention solutions when faced by a lack of hard data.

Others have highlighted similar problems: ‘[the data] can only been seen as a measurement of how respondents currently feel about each of the factors they are requested to make estimations about – they are socially constructed and more than likely a distorted picture of the problem based upon personal prejudice.

Sampling methods can also be seen to have a major impact upon the types of results generated by the various shrinkage surveys. For instance, the various versions of the Retail Fraud Surveys, which have now been undertaken in both the UK and USA, have produced what might be regarded by some in the industry as rather counter-intuitive results, certainly compared with those found in other surveys. For instance, the 2016 UK survey found that shoplifting was ranked fourth in causes of loss behind internal cash theft, which was ranked third, behind administrative/ book-keeping errors and employee theft of stock. No other published survey has ever ranked cash theft so highly, or indeed included this category in their possible explanations of shrinkage! It is unclear how these ranking have been calculated and whether or not the responses were weighted according to the size and scale of the respondent, but the sample does include a significant number of Fast Food/Leisure companies, such as MacDonalds, Pret-a-Manger, Gala Bingo, Café Nero, and Pizza Hut, which may go at least some way to explaining the prominence of internal cash loss in this survey.

The more recent variants of the Global Retail Barometer have added further fog to the already murky world of defining loss by calculating what is described as the ‘Global Cost of Retail Theft/Crime’. This is based upon removing the guesstimated costs for ‘administrative errors, such as accounting and pricing mistakes’ and replacing them with an estimation of the cost of providing loss prevention and putting this number together with the guesstimates for the amount of loss caused by dishonest employees, shoplifters, and fraudulent suppliers. The Report then goes on to compare these numbers between 24 different countries and four global regions, concluding that Europe was the only region that witnessed ‘a fall … driven by [a] fall in shrinkage and spend on loss prevention’. As detailed above, there comes a point when basing such detailed comparisons on guesstimates that are themselves based upon calculations of unknown losses has the real danger of becoming a rather perverse exercise in speciousness.

Without doubt, some of these surveys have played an important role in helping the loss prevention industry understand how it is thinking about the problem of loss. Other parts of these surveys, which for instance, focus upon the extent of the use of various approaches to managing loss, have been important in providing benchmark data. But the rapidly changing retail landscape, together with the way in which retailing is not only experiencing a broader range of losses, but is also growing its capacity to collect and analyze data on them, would suggest that a new approach to benchmarking retail losses may well now be required.

Summary

The review of the existing literature on how shrinkage is defined and understood can be summarized as follows:

- There is no agreed definition of what constitutes ‘shrinkage’.

- Most published estimates of shrinkage are based primarily upon measures of unknown loss where the cause is generally unidentifiable.

- The focus of most definitions of shrinkage typically relate only to the loss of merchandise.

- In most surveys the measurement of shrinkage is requested at store level – the ‘retail supply chain’ rarely features.

- There is little consensus on how shrinkage should be measured although most surveys collect information at retail prices.

- The categorization of shrinkage is confusing and often relies upon catch all phrases that lack firm definitions or seem incapable of capturing the various types of risks associated with an increasingly complex retail environment.

- The terms ‘retail crime’ and ‘shrinkage’ are sometimes used interchangeably with the former including the costs of responding to losses, while the latter may or may not be based upon known and unknown losses.

The Parameters of Total Retail Loss

Differentiating Between Retail Costs and Retail Losses

One of the difficulties of benchmarking any retail business using the indicator of ‘shrinkage’ is the problems associated with understanding what categories of retail ‘loss’ are included or excluded, particularly under the rather catch all terms of administrative error/process failures. Some companies taking part in this research adopted very strict criteria – shrinkage is only the value of their unknown losses based upon the difference between expected and actual stock number/values, with anything else being regarded as known and therefore not included in the calculation. Other companies were much more inclusive, incorporating a number of other types of loss, ranging from damages, wastage, spoilage, price markdowns, to the costs of burglaries, robberies and even predicted losses from Organized Retail Crime (ORC). Some of the respondents, however, were increasingly concerned about the continuing applicability of the term ‘shrinkage’ in a modern retail context:

Listen, I think the word has become obsolete because loss prevention has evolved into asset protection, and now it’s asset profit and protection, and god knows where it’s going to be three years from now … the names have changed, the roles have changed, the roles have gotten significantly wider, but we still hang on to this word that we’ve been using that describes something that we did 100 years ago, so I’m kind of fascinated that we still … I actually don’t like using the word shrink – think about it, look how complicated retail has become right? Before it would just be stores, and now we’re looking supply chain, you’re looking at corporate, you’re looking at online … it’s becoming complicated and quite frankly shrink just doesn’t, it’s just not it. (Resp. 87).

Part of this definitional variance seemed to be based upon how respondents interpreted the difference between what could be regarded as a ‘loss’ compared with a ‘cost’, the latter being viewed as everyday planned and necessary expenditure in order for the business to achieve its goal of making a profit. Indeed, the various ways in which respondents described this difference was highly instructive in understanding why there seems to be such variance in what categories of ‘loss’ are included/excluded within organizational definitions of shrinkage. Respondents employed a veritable smorgasbord of phrases and terms to describe the difference between a cost and a loss, including: controllable and uncontrollable; planned and unplanned; recoverable and non-recoverable; intentional and unintentional; budgeted and unbudgeted expenditure; recorded and unrecorded; agreed and not agreed expenditure, to list but a few. A common distinction, however, was offered by one respondent: ‘There is a sense that when it becomes recordable then it becomes regarded as a cost whereas if it is unknown then it is a loss’ (Resp. 8). Another said: ‘controllable is cost and uncontrollable is loss … [cost is] something I purposefully decided that I am willing to take on whereas a loss is something I can’t control’ (Resp. 6). This distinction was particularly blurry when it came to losses that were associated with retail margin, such as markdowns and discounting practices:

Markdowns; that’s just a cost of doing business (Resp. 45); Markdowns are a cost of doing business, the business may want to record the value of the markdowns but they are a cost and not a loss (Resp. 5); The issue comes down to what we call it and how it is accounted for within the business. For some it is just part of the cost of doing retail business – an inevitable and acceptable part of the game of selling goods to consumers while trying to make a profit (Resp. 97).

Another respondent only considered the loss of physical items as a loss – margin losses were simply part of costs, whereas another kept their definition really very simple: ‘loss is a cost that you don’t need to have’ (Resp. 19). However, a considerable number of respondents made a key distinction between the ‘value’ of the outcome and how this differentiated costs from losses:

… costs – they bring value to the business, they are incurred because there is a perceived positive purpose in having them – they are part of the revenue generation process and without them profits would be negatively impacted (Resp. 61); Losses are things which if they didn’t happen there would be no negative impact upon profitability, they do not offer any real value to the business and simply act as a drain on profitability (Resp. 88).

Others agreed: ‘For me costs are decisions that are made to drive business outcomes – it’s an investment, cost is an investment. So we are a cost center, profit protection is a cost center, it’s an investment [the business is] investing in us to get a result of less loss. Losses on the other hand don’t offer any value at all’ (Resp. 90).

It was also instructive to hear how some respondents adopted a process of ‘normalizing’ what some considered to be losses into costs: ‘… we plan a lot of those costs [possible types of losses], so when we’re looking at it from a planning perspective, we have that built in – anything that we can account for and process and know what it is, we take more so as a cost rather than a loss, when we’re defining it’ (Resp. 66). Another talked about how the planning and budgeting process enabled many losses to be redefined as costs: ‘if it goes above budget then it becomes a loss otherwise it is a cost’ (Resp. 84). Interestingly, one respondent reflected upon the dangers of this approach of ‘hard baking’ losses into costs:

People always viewed it [worker’s compensation] as a cost of doing business but I think we’ve been incredibly innovative and we’ve shown that no, you can really change the way we do things … when you view it as a cost to doing business, that’s when you lose innovation and when you lose really looking at how do you prevent [it]. We’ve done some incredibly strategic things around here in that area, in particular, I can just remember the conversations when we were doing it, it was like, a lot of people thought don’t mess with that, that’s just going to be what it’s going to be, it’s just going to gradually increase every year’ (Resp. 78).

This is a good example of how by labelling something as a ‘cost’ it can begin to drive particular behaviors and this can be particularly the case when a budget or target is set for a given cost/loss. Not unlike speed limits on roads, where the notified maximum speed is not necessarily the speed at which you should travel, but more advice on the speed you should not exceed, agreed budgets for costs/losses can drive similar behaviors. It is also worth noting that many respondents adopted a much more accepting tone when types of expenditure were described as ‘the cost of doing business’ – a reassuringly benign phrase, which seemed to absolve them of taking responsibility for the consequences: ‘we try and convert as much of this [losses] to costs – it’s then not on my agenda anymore – I deal with shrink’ (Resp. 1).

Defining Total Retail Loss

Drawing a distinction between what can be regarded as the costs of doing business and what might be considered as a loss to the business is vitally important in drawing the boundaries around a proposed definition of Total Retail Loss. From the interviews with senior US retail executives and feedback from the roundtables held in Europe, a proposed definition of costs and losses is suggested as the following:

Costs:

Expenditure on activities and investments that are considered to make some form of recognizable contribution to generating current or future retail income.

Losses:

Events and outcomes that negatively impact retail profitability and make no positive, identifiable and intrinsic contribution to generating income.

Using these definitions, various types of events and activities can begin to be categorized accordingly. For example, incidents of customer theft can clearly be seen to be a loss – the event and outcome plays no intrinsic role in generating retail profits – it makes no identifiable contribution whatsoever and were it not to happen, the business would only benefit. Alternatively, incidents of customer compensation, such as providing a disgruntled shopper with a discounted price, can be seen to be a cost. In this case, the business is incurring the cost because it believes that by compensating the aggrieved consumer they are more likely to shop with them again in the future – the policy of compensating is regarded as an investment in future profit generation and is therefore categorized as a cost and not a loss.

Another example of a potential loss is workers’ compensation, where a retailer will cover the legal, medical and other costs associated with an accident at work, such as a member of staff being hurt falling off a ladder. There is no intrinsic value to the business of a member of staff incurring an injury while at work – if it had not happened, the business could only benefit through not having to pay out for the consequences of the event. It is therefore a loss and while a number of respondents to this research argued that it is a predictable and recognizable problem that can and is budgeted for, it still remains an event that ideally the retailer would prefer not to happen as it impacts negatively on overall profitability.

In contrast, expenditure on, for instance, loss prevention activities and approaches, such as employing security guards or installing tagging systems can be seen as a cost. The retail organization has committed to this expenditure because it feels there will be some form of payback from the investment – lower levels of loss which in turn will boost profits.

What these examples focus upon is not whether an activity or event can be controlled or not, or whether the incurred cost was planned or unplanned, but upon its fundamental role in generating current or future retail income. Where a clearly identifiable link can be made between an activity and the generation of retail income then it should be regarded as a cost, where as all those activities and events where no link can be found should be viewed as a loss.

Before moving on to think about the range of types of loss that might be included in a Total Retail Loss typology, it is worth exploring in a little more detail a range of costs that have sometimes been included within various definitions of shrinkage and retail loss and what a number of respondents to this research described as ‘margin eroders’.

Margin Eroders – Cost or Loss?

What became apparent from this research is that there are a number of events and activities that do have a negative impact upon retail profitability but do not meet the criteria described above of being categorized as a ‘loss’. These were often described as ‘margin eroders’ – planned and unplanned activities and behaviors which, strictly speaking, negatively impact upon overall retail profitability, but nevertheless, can be seen as having a beneficial role to play in helping the business generate current and future profits, and hence can be seen as a cost. Respondents to this research frequently described them as the:

‘costs of being a retailer – part of the business of trying to sell stuff to customers’ (Resp. 3); ‘Mark downs are typically baked into business assumptions across the year – we know we are going to have to do it and it is just the cost of doing business as a retailer. That’s not to say we don’t monitor the number internally, it’s just we wouldn’t see that as a loss’ (Resp. 60).

In this respect they were seen as having some form of identifiable role to play compared with losses, which, as detailed early, have no intrinsic value whatsoever to the business. For example, product markdowns, customer guarantees, staff discounts, price matching guarantees, customer compensation, food donations and so on. All these business ‘choices’ can be regarded as investments – product markdowns improve the prospects of some value being received for the item; price matching, customer guarantees and compensation schemes are an investment in goodwill to try and ensure that recipients continue to be customers in the future.

This is not to say that a business would not want to measure and monitor the extent to which these factors erode margin and business profits and analyze whether rates varied across the business (do some stores offer more discounts than others for instance?), in order to gauge whether they remained a good strategic investment. But they should be viewed as something different from retail losses – they are part of the costs of being a retailer and as such it is suggested that they should not be included in the Total Retail Loss Typology.

Categorizing Total Retail Loss

Given that losses are all the events and outcomes incurred in a retail business that have no intrinsic value, it is now worth considering what the various types of losses might be and to try and organize them thematically. But before doing this, it is important to draw a distinction between the types of loss that can be Measured, and measured in a way that is Manageable for a modern retail business, and those that cannot. In addition, it is important to consider the value of collecting data on a given loss indicator – is it Meaningful for the business to monitor this particular loss variable – will its analysis offer potentially actionable outcomes that may help the business meet its objectives? As one respondent said: ‘I think the biggest key in a lot of this keeps coming back to can we apply a number to it with some level of accuracy? If we can, then I think it becomes very productive to measure it as a loss’ (Resp. 90). Another put it rather succinctly: ‘measurement is key and you can’t measure a mystery’ (Resp. 16).

There is little point, therefore, developing a typology made up of a series of categories that are either impossible or implausibly difficult to measure or once measured offer little benefit to the business undertaking the exercise. For example, most retailers would no doubt be keen to understand how many times items are not scanned at a checkout or the exact value of all deliveries where there is a short shipment. While both of these measures are theoretically possible to achieve, the reality for most retailers is that the cost of systematically calculating these numbers would probably be prohibitive to do on a regular basis (with current technologies and business models). Determining whether proposed loss categories meet the 3 ‘M’s test (Manageably Measurable and Meaningful) is an important part of creating a typology that is likely to achieve any form of adoption across a broad range of retail formats.

It is also worth noting that while this report is advocating the use of the term ‘Total Retail Loss’ to better capture the range of losses occurring across the retail landscape, it fully recognizes that the associated typology does not necessarily encompass every form of loss that a retailer could conceivably experience. The word ‘Total’ is being used in this context to represent a much broader and more detailed interpretation of what can be regarded as a retail loss, rather than necessarily claiming to be a reflection of the ‘entirety’ of events and activities that could constitute a loss. For instance, there are a number of potential losses not considered in this report, such as those associated with brand reputation, lost sales associated with counterfeit goods and the grey market, as well as lost sales that may arise from stolen product being sold on Internet auction sites. While some of these types of losses are beginning to be better understood, becoming more visible and measurable, as yet they remain, for most retailers, highly problematic to calculate with any degree of confidence. No doubt in the future the scope and range of ‘Total Retail Loss’ will change to accommodate new forms of manageably measurable and meaningful losses and this is to be welcomed. Like retail itself, the world of loss prevention needs to continually adapt to meet the demands of a highly dynamic sector of the global economy.

Known and Unknown Losses

The starting point for the proposed typology is to recognize that there are two types of losses incurred by retailers – those that are unknown, where the cause is unidentifiable, and those where the cause is known, with a reasonable degree of certainty. As detailed earlier, most existing definitions of shrinkage and associated surveys tend to rely upon a calculation generated by comparing the difference between the value of expected inventory with actual inventory levels. This is usually done through some form of physical audit undertaken periodically, usually once or twice a year. For the vast majority of retailers, this generates an unknown loss number – the audit process rarely if ever generates data that might give a sense of where, when or indeed how losses occurred. It is important, therefore, that losses recorded in this way are recognized for what they are: ‘Unknown Stock Loss’, as the number only relates to lost stock and the causes of these losses are typically unknown. It is critical to note at this point that it is strongly recommended that there should not be any efforts made to try and ‘guess’ what proportion of unknown losses may be due to particular causes (such as the typical four buckets of shrinkage seen in most surveys) and include these in known losses. Unknown losses are called ‘unknown’ for a reason and if loss prevention practitioners wish to grow their credibility with other parts of the industry, they must increasingly move towards the proper analysis and representation of their data – speculative guesswork is only likely to generate more skepticism and further widen the credibility gap.

There are then losses where the cause of the loss is known, sometimes with a high degree of certainty and at other times with a lower level of confidence.

For instance, product that has gone beyond its sell by date and has to be thrown away is often recorded by a retailer – the value of the items discarded is known, as is the cause. If items are thrown away without being recorded, they will eventually appear in the unknown loss category. Equally, some retailers request that staff record the value of items where discarded packaging has been found in a store, strongly indicating that it has been stolen by a customer, or where an on-hand count from one day to the next reveals a significant and obvious loss of a product (through for instance a suspected sweep theft at the shelf). In these instances, then the loss should be recorded as incidents of ‘Known External Theft’ – the degree of confidence in the cause of the loss is lower than in the first example, but as long as the retailer has recognizable policies and practices in place to record these types of loss, then it still has value.

As will be detailed below, it is possible to identify a significant number of known forms of loss – 31 in total covering a wide range of losses across the retail enterprise and incorporating events and outcomes beyond just the loss of merchandise. This list of known causes is still a work in progress and it is hoped that future research and application of the proposed typology will enable it to be further fine-tuned and amended to ensure it has as high a degree of applicability across as many types of retailing as possible.

Known Losses: Malicious and Non Malicious

It is proposed that the causes of known retail losses can then be subdivided into two groups: malicious and non malicious forms of loss. ‘Malicious’ refers to those activities that are carried out to intentionally divest an organization of goods, cash, services and ultimately profit, while ‘non malicious’ relates to events that occur within and between organizations that unintentionally cause loss. The importance of understanding the intentionality of a loss occurrence is the impact it has upon the approach adopted to address it and the expected longevity of the results of an intervention. Malicious losses are intentional and occur deliberately with a degree of forethought. To a certain extent such losses occur when existing systems have been found to be vulnerable – sometimes by accident, often by ‘probing’ – and are duly ‘defeated’ by the offender. For example, the use of closed circuit television has been found to have only a short term impact – thieves are initially deterred by the new intervention but as familiarity grows and the systems are ‘tested’ and defeated, any long term impact on levels of loss may be limited. As such, remedial action to deal with some types of malicious activity will have a ‘half-life’ where their effectiveness deteriorates over time as offenders find new ways to overcome them. Remedial actions can also lead to displacement where offenders target different products, locations, times or methods.

Unintentional or non-malicious loss is usually less dynamic and more responsive to lasting ameliorative actions. For example, damage caused by loads shifting during transport can be addressed by employing new methods of pallet stacking and methods for restraining loads inside the vehicle. While this intervention may require similar levels of vigilance (for instance to make sure staff are continuing to follow procedures) it is more likely to have a lasting effect than interventions where a malicious actor is constantly probing for weakness and opportunity. It is therefore considered useful to categorize known losses into malicious and non malicious.

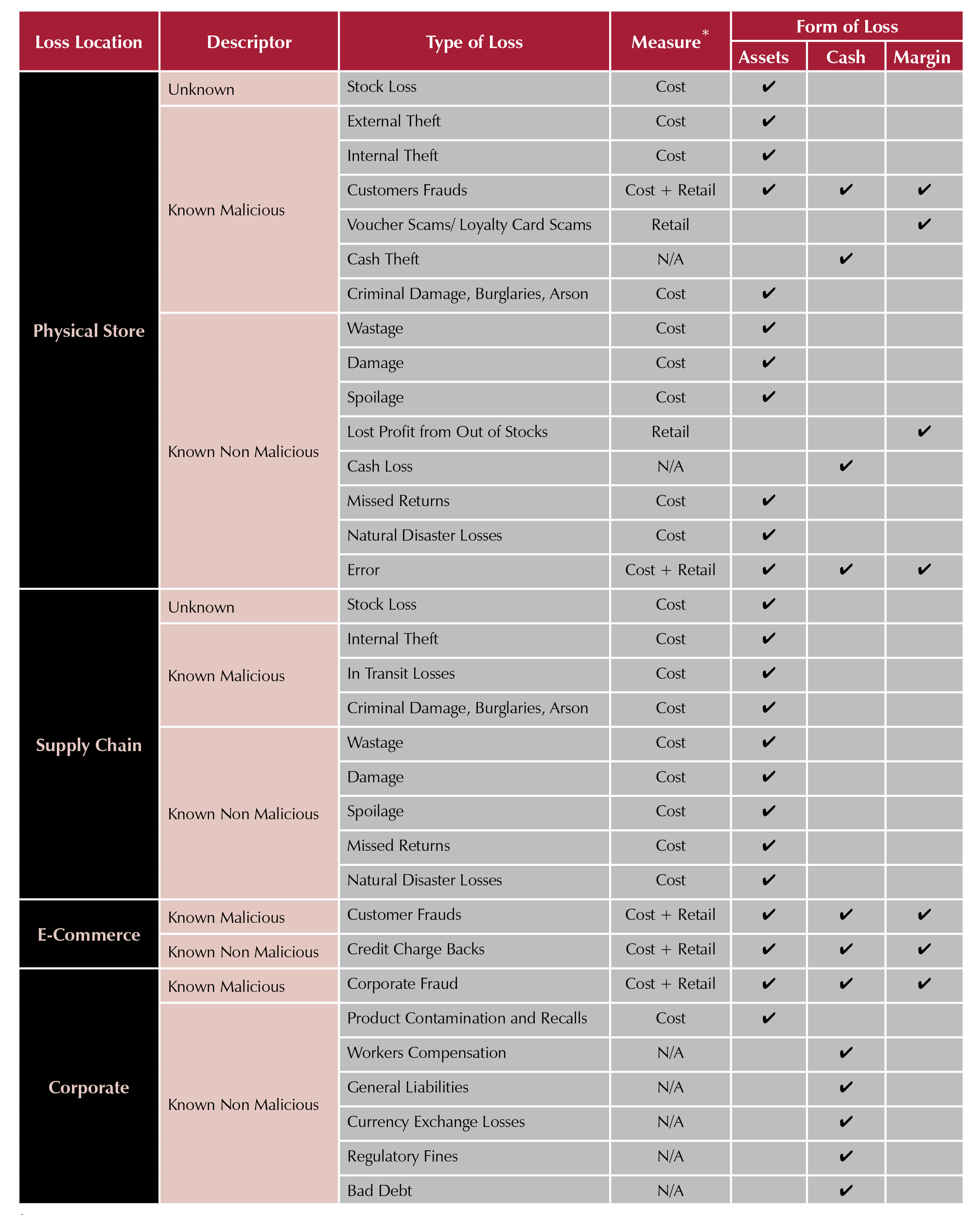

Locating Total Retail Loss

Beyond categorizing losses in terms of being known and unknown, and malicious and non malicious, it is also important to provide some form of organizational framework within which they can be located. When losses are predominantly/exclusively focused upon the loss of stock, as is the case with existing definitions of shrink/shrinkage/shortage, then the location is largely determined by where the stock can be counted – usually the physical store or in some circumstances the distribution center. However, when the definition of loss is broadened to take into account all events and outcomes that negatively impact retail profitability and make no positive, identifiable and intrinsic contribution to generating income, the range of possible ‘locations’ inevitably increases beyond just the store and the distribution center.

It is therefore proposed to group the losses under four ‘centers’ of loss, only some of which might be actual physical locations. When deciding what categories of loss should be allocated to each of these centers, the practicalities of measurement played an important role as did the extent to which the losses could be in some way controlled by those operating in each of these centers. Of course, the retail environment is complex and trying to achieve a structure that would satisfy all variants of retailing is impossible and a degree of compromise and ‘fudging’ is inevitable. A case in point is E-commerce and how this type of activity is organized and operated across different retailers – probably best categorized by difference rather than uniformity. At the same time, it is also an increasingly important part of the future of retailing and is already generating new forms of loss that need to be recognized and managed.

Given this, broad definitions of the proposed four centers of loss are offered below:

Stores: Losses that occur in the physical buildings owned or rented by a retailer where customers can purchase products and where E-commerce activities may be undertaken such as shipping of product, customer pickups and returns.

Retail Supply Chain: Losses occurring across the entire process of manufacture, transportation and storage of products for which the retailer has ownership and liability. This includes where appropriate, E-commerce activities such as managing fulfilment centers, shipping of product to customers and dealing with returns.

E-Commerce: Specific losses related to the provision of goods and services provided through some form of on-line/Internet-based interface, enabling customers to purchase goods/services without necessarily visiting a physical store.

Corporate: A category of losses which are typically related to the broader activities of the business, beyond those necessarily occurring in stores, the retail supply chain or E-commerce, or where the overall loss is not allocated directly to these centers.

Undoubtedly, as the nature and influence of E-commerce grows, then categories of known loss may be more appropriately situated under this heading than in other areas – the difficulty lies in having manageably measurable categories of loss that are meaningful to the user of the Typology.

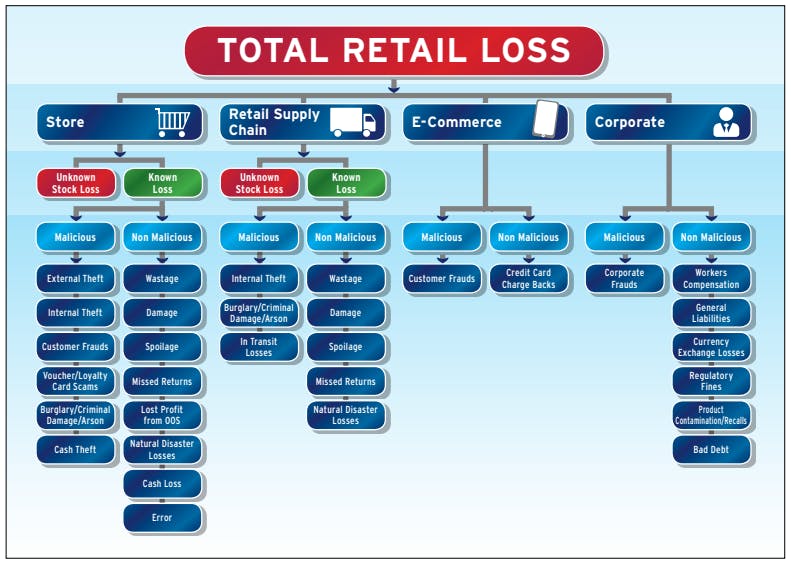

The Total Retail Loss Typology

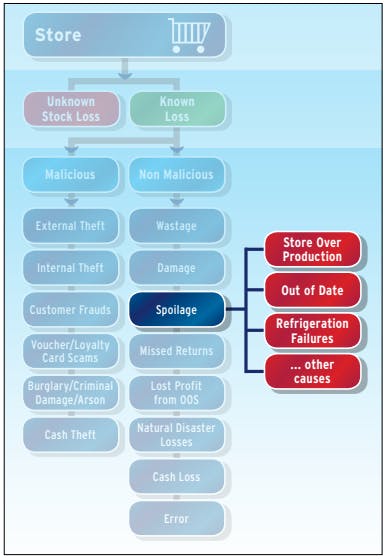

Outlined below is the proposed typology of Total Retail Loss, organized around the four ‘centers’ of loss and breaking losses down firstly into known and unknown before further dividing the known losses into malicious and non malicious in nature.

It is important to note that the Typology is designed to enable the ‘value’ of retail losses to be calculated and not necessarily the number of events – where an associated ‘value’ cannot be calculated or there is no loss of value associated with an incident, this should not be included. For instance, if a shoplifter is apprehended leaving a retail store and the goods they were attempting to steal are successfully recovered and can be sold at full value at a later date, there is no financial loss associated with this incident. That is not to say that the retailer may still want to record the fact that an attempted theft took place and was successfully dealt with, but that it would not be recorded in the Total Retail Loss Typology. In this respect the Typology is recording the value of retail losses and not their prevalence. However, if in the above example, some of the products that were recovered from the wouldbe shoplifter could not be sold (because they had to be kept for evidential purposes or had become damaged), then their cost price would be included in the category of ‘External Theft’ as the retailer has genuinely incurred a loss through this event.

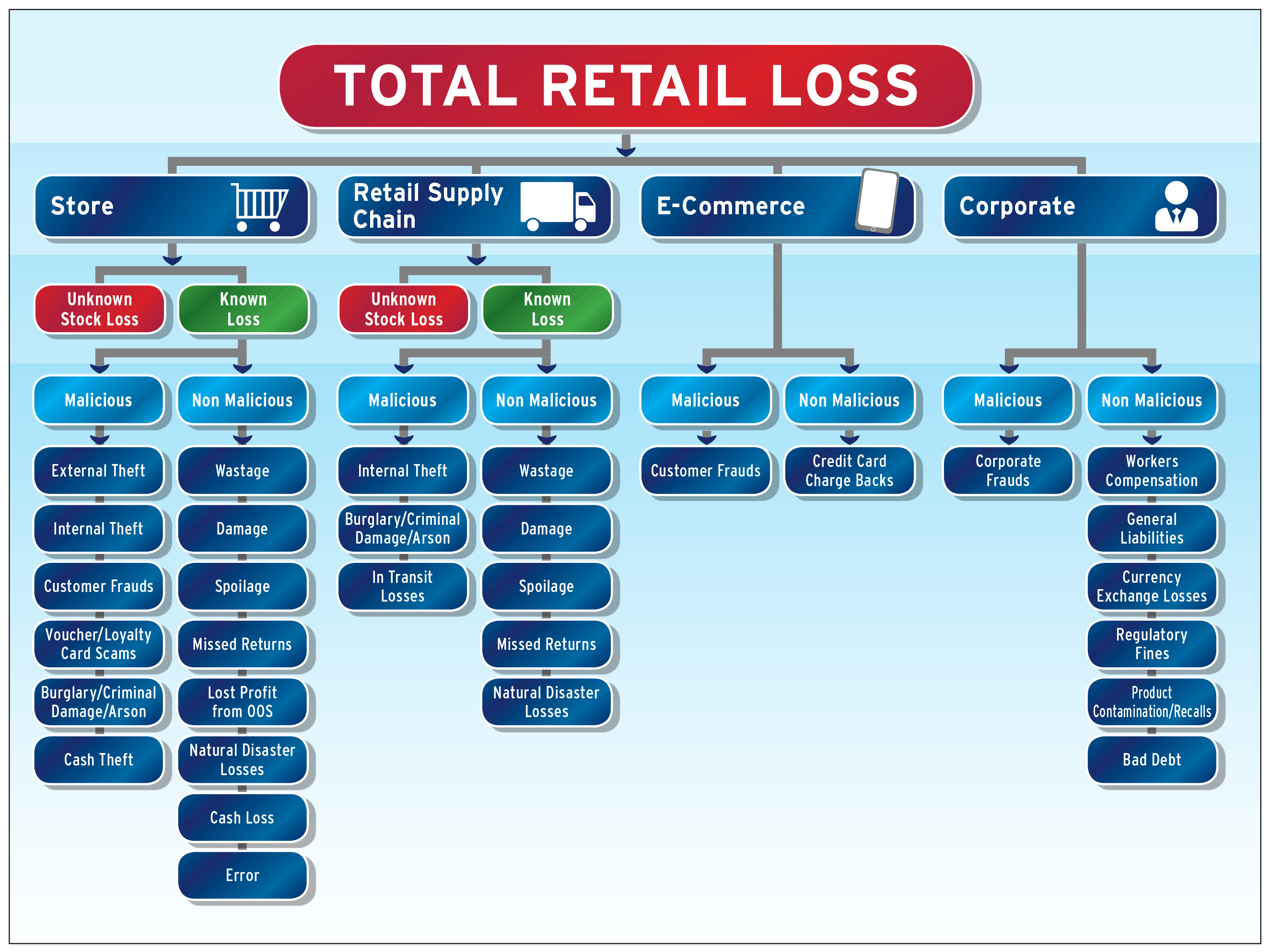

Figure 1 The Total Retail Loss Typology

Categories of Store Losses

As can be seen in Figure 1, 14 categories of known loss are proposed for the losses that are seen to take place in physical stores. In order to try and minimize the confusion around the terms being used, which has plagued some of the regular shrinkage surveys, it is proposed to offer the following definitions of each of the proposed categories of loss, starting first of all with Unknown Store Stock Loss, which is the nearest category to many of the existing definitions of shrinkage/shrink/shortage:

Unknown Store Stock Loss: The difference between the anticipated and actual value of stock in retail stores, typically calculated through store audits/ on hand adjustments, measured at cost price. It should exclude every other form of known loss such as damages and spoilage or ‘margin eroders’ such as markdowns and discounting (see earlier).

Known Store Losses: Malicious

External Theft: The value at cost price of stock that is known to have been stolen by third parties not employed by the retail company. This should include instances where stock is seen to have been removed from a store but is non recoverable or where it is recovered but no longer able to be sold. In addition, where there is plausible evidence that external theft has occurred, such as empty packaging, sudden documentable changes in on-shelf stock levels etc., then these losses should also be included. The value of any retailer-specific stock recovered as part of investigations to counter external theft that is deemed unsellable should be added to the External Theft value, but an equal amount should be deducted from the Unknown Store Stock Loss total if the thefts were deemed to have taken place in the same financial accounting period.

Internal Theft: The value at cost price of stock that is known to have been stolen by members of staff directly employed by the company and which, even if recovered, cannot be sold. Where investigations unearth plausible evidence of the value of previously stolen stock that is not recoverable for sale, this should be added to the Internal Theft value, but an equal amount should be deducted from the Unknown Store Stock Loss total if the thefts were deemed to have taken place in the same financial accounting period. This value should not include any estimations of what may have been stolen in the future had the offender not been caught. If evidence of previously stolen cash is also unearthed, then this should be added to this total but an equal amount should be deducted from the Known Non Malicious Cash Loss total if the theft(s) were deemed to have taken place in the same financial accounting period.

Customers Frauds: The value of a range of known frauds committed by customers, which include: Returns Fraud (items returned without a valid receipt, calculated as the full retail value of the merchandise); Gift Card Frauds (various manipulations of gift cards to either accrue false credit or purchase items, calculated at the cost price of items); Bad Cheques (payment made with a cheque which has no redeemable value, calculated at the cost price of the merchandise); Credit Frauds (bogus customer sets up a credit account, usually with stolen identity documents and ‘purchases’ merchandise or gift cards, calculated at cost price of items lost); Stolen Credit/Bank Cards (goods are purchased before the theft is recorded but the value is then charged back to the retailer by the bank/credit card company, calculated at full retail value of the merchandise).

Voucher/Loyalty Card Abuse: The total lost margin where customers and employees use vouchers in ways in which they were not originally intended, such as multiple use of a single use voucher or the use of multiple vouchers on items where only a single voucher should be used. Note that the losses from not redeeming the value of used vouchers from Vendors/ Suppliers is covered under Missed Returns. In addition, the total lost margin where a loyalty card is used to purchase merchandise by somebody not entitled to use it, should be included in this calculation.

Cash Theft: The total value of stolen cash where the loss is known and the cause was malicious, such as a till grab/robbery, or a raid on a cash office. Cash stolen in transit should only be included where the loss is incurred directly by the retailer and not by a 3rd Party cash handling company

Burglary, Criminal Damage and Arson: The total value of all incidents of Burglary (where offenders forcibly enter a retailer’s premises while they are closed), Criminal Damage (where property, including buildings and vehicles, of a retailer are damaged) and Arson (where property, including buildings and vehicles are purposefully set on fire). The value should be calculated as the cost price of all items identifiably stolen or damaged (and unsellable) together with the cost of repairing or replacing the property damaged. The total value should be calculated minus of any payments received from third parties such as insurance companies or where the liability for the cost of repair is met directly by them.

Known Store Losses: Non Malicious

Wastage: The total value at cost price of all non-food stock that is removed from a retailer’s store inventory without any value being received for it, including stock liquidations when stores are closed. This should take account of any allowances from Vendors/Suppliers to compensate for this type of loss (such as fixed allowances or a returns process for unsold stock where credit is received) together with any income received from stock reclamation companies.

Damage: The total value at cost price of all non-food stock that is removed from a retailer’s store inventory without any value being received for it because the stock is deemed to be damaged. This should take account of any allowances from Vendors/Suppliers to compensate for this type of loss (such as fixed allowances or a returns process for unsold stock where credit is received) together with any income received from stock reclamation companies.

Spoilage: The total value at cost price of all food-related stock that is removed from a retailer’s store inventory without any value being received for it, typically because it has gone beyond its sell by date or it has been damaged to the extent it cannot be sold. This figure should exclude an income from markdown activities – it only relates to the value of goods where no value has been received. Any compensation received from Vendors/Suppliers or revenue (such as tax deductions) through food donations should be offset against this loss.

Missed Returns: The value of missed imbursements for not returning stock to a Vendor/Supplier according to a particular process or within an agreed time period. Retailers should ensure these losses are not also counted within Wastage or Spoilage losses.

Lost Profit from Out of Stocks: The total value of the lost margin on merchandise identified as out of stock on the shelf that it is calculated would have been purchased by a consumer had it been available. Retailers vary considerably in how they measure Out of Stocks/On Shelf Availability and the amount of margin that has been lost as a consequence. Research suggests that 47% of out of stock events result in a lost sale although this figure varies considerably depending upon the type of merchandise and location of the retailer. Further research is required to develop an industry standard on how this might be calculated and so at this stage the value should be based upon the best measures available within each retailer utilizing the Total Retail Loss Typology

Natural Disaster Losses: The total value of all adverse events that would be considered as natural processes related to the earth, such as floods, hurricanes, tornados, earthquakes etc. The losses should be calculated on the cost price of all merchandise that is considered to have no redeemable value together with the cost of repairing the damage to property (buildings and vehicles) caused by the event. Any costs that can be redeemed from third party insurance companies and any value for merchandise offered by reclamation businesses should be offset against this loss. No allowance for lost sales should be included in this calculation.

Cash Loss: The total value of all known cash losses where the cause is not regarded as malicious (such as miscounting and errors at the till).