Measuring the Impact of RFID in Retailing

Keys Lessons from 10 Case-study Companies

Table of Contents:

- Abstract

- Introduction

- - Research Objectives

- - Methodology

- The Use and Business Cases for RFID in Retail

- Getting Started on an RFID Journey

- - Choose a Business Leader

- - Engage the Business

- - Seek External Help

- - Choose RFID Technologies

- Undertaking a Trial

- - Proof of Concept Trials

- - RFID Pilot Trials

- - Measuring the Impact of RFID

- Measuring the Impact of RFID

- - Sales

- - Inventory Record Accuracy

- - Out of Stocks/On Shelf Availability

- - Inventory Management & Stock Holding

- - Stock Loss / Shrinkage

- - Price Discounts / Markdowns

- - Cost of Inventory Counts / Audits

- - Productivity / Staff Costs

- - Measuring Key Performance Drivers (Lead Measures)

- - Return on Investment

- Deploying and Rolling out RFID

- - Making the Case

- - Planning the Roll Out

- - Rolling Out

- - Training and Awareness

- - Impact on Audit

- - Living with RFID

- - Getting Systems to Talk

- Loss Prevention and RFID

- - Loss Prevention in Context

- - Vulnerability of Tags

- - Exit Gate Reliability

- - Enabling Innovation

- - Identifying Hot Products and Amplifying Risk

- Learning Lessons

- - Understand Your Business

- - Clearly Articulate the Need

- - Ensure Board Level Support and Engage Stakeholders

- - Understand the Technology

- - Avoid Tagging in Store

- - Recognise the Omni Channel Imperative

- - Standards Matter

- - Undertaking Trials

- - Measuring Impact

- - Rolling Out RFID

- - Integrating RFID-Generated Data

- - RFID is an Ongoing Journey

- - Keep it Simple

- Future Developments

- Summary of Key Findings

Languages :

This report focusses on capturing the detailed experiences of 10 retail companies that have invested in RFID technologies – understanding their decision to invest, reflecting on some of the results they have achieved, and charting the lessons (both positive and negative) they are able to share from their RFID journeys.

Most of the companies that agreed to take part were Apparel retailers, adopting a range of both small and large-scale RFID systems. Collectively, these companies have overall sales in the region of €94 billion a year and are using at least 1.87 billion tags a year – equivalent to about 60 tags per second.

The research found five key reasons why retailers invested in this technology: drive sales through improved inventory visibility and accuracy; optimise stock holding, reducing capital outlay and improving staff productivity; have fewer markdowns, limiting the volume of stock offered at discounted prices; help to drive innovation and business efficiencies, often seeing RFID as an enabling technology; and facilitating the effective delivery of an omni channel business strategy.

The study found that participating retailers had generated some impressive results from investing in RFID: an increase in sales of between 1.5% and 5.5%; improvements in stock accuracy from 65%-75% to 93%-99%; significant improvements in stock availability, often in the high 90% region; stock holdings reduced by between 2% and 13%; lower levels of stock loss; reduced staff costs; and all 10 participating companies were unequivocal in their assertion that the ROI had been achieved.

The report goes on offer a series of lessons learnt from the case study companies. This included: the importance of active senior management support for the initiative; appointing a business leader who had responsibility for on shelf availability/stock integrity; making sure the business was engaged; there was clear awareness of the business context; that the significant challenges of data integration were understood and addressed; and that there was a clear strategy in place for measuring the impact of introducing RFID into the business. Finally, the report recommends that those planning to embark on an RFID journey ensure that they keep it simple – do not make it over complicated, and remember RFID merely provides data; if you do nothing with it then the project is destined to fail.

Abstract

This report focusses on capturing the detailed experiences of 10 retail companies that have invested in RFID technologies – understanding their decision to invest, reflecting on some of the results they have achieved, and charting the lessons (both positive and negative) they are able to share from their RFID journeys.

Most of the companies that agreed to take part were Apparel retailers, adopting a range of both small and large-scale RFID systems. Collectively, these companies have overall sales in the region of €94 billion a year and are using at least 1.87 billion tags a year – equivalent to about 60 tags per second.

The research found five key reasons why retailers invested in this technology: drive sales through improved inventory visibility and accuracy; optimise stock holding, reducing capital outlay and improving staff productivity; have fewer markdowns, limiting the volume of stock offered at discounted prices; help to drive innovation and business efficiencies, often seeing RFID as an enabling technology; and facilitating the effective delivery of an omni channel business strategy.

The study found that participating retailers had generated some impressive results from investing in RFID: an increase in sales of between 1.5% and 5.5%; improvements in stock accuracy from 65%-75% to 93%-99%; significant improvements in stock availability, often in the high 90% region; stock holdings reduced by between 2% and 13%; lower levels of stock loss; reduced staff costs; and all 10 participating companies were unequivocal in their assertion that the ROI had been achieved.

The report goes on offer a series of lessons learnt from the case study companies. This included: the importance of active senior management support for the initiative; appointing a business leader who had responsibility for on shelf availability/stock integrity; making sure the business was engaged; there was clear awareness of the business context; that the significant challenges of data integration were understood and addressed; and that there was a clear strategy in place for measuring the impact of introducing RFID into the business. Finally, the report recommends that those planning to embark on an RFID journey ensure that they keep it simple – do not make it over complicated, and remember RFID merely provides data; if you do nothing with it then the project is destined to fail.

Introduction

Background and Context

Since the term Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) came into common usage within the retail environment, around the end of the 1990s, it has in many respects been an idea driven more by hope and hype than practical realisation. It is closely linked with the ‘Internet of Things’ concept whereby all manufactured objects have the capability to be uniquely identified and the capacity to do this without the need for line of sight. For retailers it promised a world where supply chains would become fully transparent, with all products identifiable in real time, bringing an end to oversupply and out stocks – the ultimate optimisation tool, allowing retailers to truly deliver ‘just in time’ supply chains tailored precisely to the needs of their customers. In addition, RFID offered other ‘game changing’ benefits such as the end of traditional checkouts and associated queuing for the consumer – products would automatically ‘checkout’ as they left the store, with the consumer’s credit card being billed accordingly.

Within the realm of loss prevention, the RFID ‘revolution’ offered much promise. With each item being uniquely identifiable in real time, it was argued shop theft would become a thing of the past as thieves would be automatically identified as they tried to leave the store without paying. Similarly, problems such as returns fraud (where a thief attempts to claim credit for an item they have not actually purchased) would be eliminated as the previous ambiguity around whether they had actually bought ‘that’ item would no longer exist – the product would ‘tell’ the retailer its current status (bought or not bought). Back in the early 2000s it seemed RFID was going to totally transform the retail world – indeed, it was described by one of its earliest advocates in the following glowing terms: ‘as significant a technology as certainly the Internet and possibly the invention of the computer itself’.

If we skip forward 17 years, then it becomes very quickly apparent that RFID, as yet, cannot be remotely put in the same category as the Internet in terms of its impact upon the world or more specifically retailing. Arguably, it is a technology that has seriously struggled to match up to the hype heaped upon it at the end of the 1990s and into the early 2000s. It continually floundered on the rocks of physics and economics, with the ‘Faraday Cage’ in many respects proving to be the prison ‘cell’ from which RFID has struggled to escape. But it also struggled to establish a strong foothold because questions about privacy and desirability often remained secondary to delivering the technological utopia of all objects being able communicate with each other and the rest of the world. A such, many of those long in the tooth in retailing have become familiar with the sentence that starts: ‘…in the next five years RFID will…’!

However, the outlook now appears to be changing fast for RFID and what has been seen in the past few years is a much more enlightened, less evangelistic and more realistic approach to how RFID may be able to play a role within retailing, one that recognises its limitations and plays to its identifiable strengths. The technology has also had the opportunity to gradually mature, away from the spotlight of unrealistic expectations, and begin to show how it can be used to help retailers resolve some of their ongoing and growing concerns. This can be seen particularly in parts of retailing that do not have a concentration of products largely made up of metals and viscous fluids, which have traditionally proved highly challenging for RFID to cope with.

Retailers focussed on apparel and footwear in particular have begun to use this technology to help them manage their supply chains more efficiently, utilising RFID’s capacity to bring transparency and ease of audit into the retail space. As pressures within retailing concerning competition and growing consumer demands for greater and more accurate availability have increased (particularly with the growth of omni channel), then some companies have begun to invest in RFID to help them respond. While we are still some way from RFID becoming ‘bigger than the Internet’, it would seem that a more gradual and incremental introduction into retailing is underway, one that recognises its weaknesses but at the same time is beginning to take advantage of developments in the technology. This movement is perhaps beginning to show that while the Internet of ‘all’ Things remains a pipe dream within retailing, the Internet of ‘some’ Things is not only becoming a reality, but that it seems to be making good business sense for some retailers to begin to invest in it.

Research Objectives

It is within this context that the research presented in this report is put forward. Back in 2002 the ECR Shrinkage Group commissioned a project to review the way in which RFID might impact upon the world of retail loss prevention – reflecting upon the prospects, problems and practicalities associated with this technology.

Since then, much has changed, and this report offers an opportunity to reflect more broadly on its recent use, offering a fresh understanding about how this technology is now being used and what lessons can be drawn from its development, its implementation and its impact on retail businesses. Based upon the detailed experiences of 10 companies that have made the commitment to invest in RFID, the report sets out to answer the following questions:

- What is the business context within which some retailers decide to invest in RFID?

- How do these companies begin their RFID journey?

- What steps do they follow when undertaking a trial?

- In what ways do they measure the impact of RFID and what have they found?

- How do they begin to roll it out to the rest of the business?

- How have they dealt with the key challenge of integration?

- What role, if any can RFID play in managing loss prevention?

- What lessons have these companies learnt on their RFID journey?

- How might they be planning to use this technology in the future?

The report begins by offering a brief overview of the research methodology used before moving on to answer each of these questions in turn. By the end, it is hoped that any company thinking about embarking on their own RFID journey will be in a better position to understand the pitfalls, practicalities and indeed benefits that may await them.

Methodology

This research was primarily interested in capturing the experiences, both good and bad, of a range of companies that had decided to invest in some form of RFID technology. It adopted a case-study methodology with data being collected via requests for various types of quantitative data relating to the use and performance of RFID, together with primarily face-to-face interviews with company representatives.

Those selected to be interviewed varied in their position within the company, but all had been involved to varying degrees with the design, implementation and review of the RFID project in their businesses. Interviews took place either in the Head Quarters of the company or one of the stores participating in the RFID project. Where it was the latter, the researcher was able to view the system in action and talk to store staff about their experiences of using it.

Interviews lasted between 65 and 150 minutes, and all were recorded and transcribed. It is important to note that this report is focussed primarily upon reviewing the experiences of the companies that agreed to take part and as such it is not intended to be a technical review of the specific RFID systems they are utilising. As such none of the technology providers being used by any of the case-study companies will be named – while it will be possible for RFID industry watchers to ascertain from the list of companies below what technologies were used, the report does not intend to offer any recommendations about what RFID systems should be used.

Participating Companies

For the most part, Apparel retailers have been at the forefront of adopting RFID technologies in recent years and so inevitably, but not exclusively, they make up the largest proportion of companies taking part in this research.

A number of companies were approached to take part based upon publicly available information on their use of RFID. It was hoped that, where possible, a range of different types of companies would be included – large and small-scale RFID projects, single and multiple country roll outs, various types of products and types of RFID systems used, and of course different types of retail environment.

Inevitably, as with much of the research carried out on retailing, particularly where some of the information required can be regarded as sensitive and potentially competitive in nature, company selection ends up being driven more by willingness to engage than any overarching systematic methodological framework. However, 10 companies eventually agreed to participate, offering a broad range of RFID experiences – some were on a very big scale (in terms of quantity of tags used), with three purchasing more than 150 million tags each per year, while others were relatively small scale, with significantly less than one million tags a year. Equally, some companies had rolled out their programmes across multiple countries while others had limited it to just one.

The sales turnover of the companies varied between about €150 million and €50 billion, with all 10 having total sales in the region of €94 billion a year. Together they accounted for at least 1.870 billion RFID tags a year, equivalent to the use of about 60 tags per second. Geographically, most companies were located in Europe, although one was based in Canada, with their RFID programme covering their North American operations, while another had rolled it out to 800 stores in 17 countries.

The 10 companies that took part in this research were:

- Adidas

- C&A

- Decathlon

- Lululemon

- Jack Wills

- John Lewis

- MARC O’POLO

- Marks & Spencer

- River Island

- Tesco

Confidentiality and Presentation of Data

Throughout this report, direct quotations are provided from the transcripts of interviews carried out with a range of representatives from the companies taking part in this research. Each quotation has been given an identifying case-study number, but due to the relatively small number of companies taking part and to avoid any particular respondent being identified across multiple quotations, this identifier has been changed for each section of the report. So for instance, code R1 refers to a different retailer in each of the sections in the report. Where respondents have provided quantitative data, this has also been anonymised and checked with the companies that agreed to take part. Where currency exchange has been necessary, the prevailing rate on the 11th December 2017 has been used.

Limitations

As with any research, there are limitations in what can be achieved and presented. While this research has attempted to offer an independent and critical review of the use of RFID in the retail sector, the case-study selection process needs to be taken into account when reviewing the findings. Because of the chosen selection criteria and the challenge of obtaining retailer support, no companies are represented that have trialled RFID and decided against rolling it out – the views of these types of company are absent from this research.

In addition, there are some companies that have adopted a different approach to using RFID than those represented in this research, namely using a hard tag variant applied either at the point of manufacturer or later in the supply chain. While one of these companies was approached to take part in the research, they declined and so it is not possible to include their experiences and views of using RFID.

As such, it is important to recognise that the general approach adopted by these 10 companies is not necessarily representative of all retail companies that are now using RFID. It is also the case that while some companies were prepared to share limited data on the efficacy of their RFID system, it was not possible to verify in any detail the reliability nor accuracy of the information shared with the researcher. Moreover, companies varied in the ways in which they measured the impact of RFID systems, and the ways in which they defined particular measures such as on shelf availability and stock integrity. Every effort has been made to try and make valid comparisons, but the challenges of undertaking secondary analysis of this type of data needs to be recognised.

Given all of that, it is hoped that the data collected from these 10 companies offers some valuable insights about their RFID journeys – the challenges they faced and the ways in which they developed their programmes to ensure that they offered both a meaningful ROI and significant opportunities for future development.

The Use and Business Cases for RFID in Retail

There were a number of reoccurring themes that emerged when respondents were asked to explain why their business had embarked on introducing RFID into their organisations, most of which were orientated around how it could improve the overall performance of the business and meet the future challenges of an increasingly competitive market.

Delivering Inventory Visibility and Accuracy

Most respondents were very clear that the primary goal of their RFID programme was to help them deal with the problem of inventory inaccuracy and its knock-on effect on out of stocks and ultimately lost sales: ‘There was growing awareness in the business about how bad our out of stocks were’[R4]. Another respondent put it very succinctly: ‘for us, [there was] only one KPI [Key Performance Indicator]: stock integrity, which generates accurate replenishment, which equals increased sales’[R7]. This respondent went on to highlight the impact errors in the supply chain had upon their store stock holding records: ‘1% of our deliveries are inaccurate and that contributes to about 30% of our stock inaccuracy because it builds every week’[R7]. Others agreed and talked about the need for, and value of, having greater visibility of their merchandise and what it could bring to the business: ‘merchandise visibility is the objective – RFID is a means to an end; ‘visibility of stock was the main reason for embarking on [our] RFID journey’[R5].

Improving Customer Satisfaction

The problem of out of stocks and it impact upon the business was also highlighted by others who focussed particularly upon its effect on their customers: ‘out of stocks was our biggest cause of customer dissatisfaction. That was the main reason for RFID’[R3]. They went on to argue that by improving customer satisfaction then ultimately sales would be improved which would justify the investment in RFID. As detailed below, customer satisfaction became an even more prescient factor when retailers begin offering an omni channel experience – the opportunities for getting it wrong can multiple considerably: ‘operating on line is tough – it is very easy to get it wrong and lose customers’[R8].

Optimising Stock Holding

Some respondents highlighted the potential opportunity presented by increased stock visibility to reduce the amount of merchandise held in the business which would impact upon not only capital outlay but also staff productivity: ‘Also wanted to reduce stock holding – less stock to handle improves productivity’[R9]; ‘[we have a] large capital investment in stock but low visibility of where it was in the business, RFID gives us the data to make better decisions about how much we should have in the business’[R5].

"merchandise visibility is the objective – RFID is a means to an end"

Helping to Drive Innovation and Business Efficiencies

While change and reinvention in retailing is nothing new, and arguably the main reason why only some retailers succeed in the long term, the increasingly dynamic nature of 21st Century retailing, epitomised by the growth of omni channel, was also part of the business context within which decisions about whether to invest in RFID were considered. Of particular importance was the perceived need for greater agility driven by improvements in the availability of data concerning not only the visibility and movement of merchandise in the business, but also the behaviours and experiences of consumers. In this respect, many respondents viewed RFID as part of a broader organisational change project – part of the evolution of their businesses where innovation is viewed as a key way to achieve future success. Some were more explicit, regarding RFID as one of the main ways in which they could continue to drive competitive advantage as part of their broader organisational transformation: ‘… it is usually best not to be the first, but you must not be the last to adopt!’[R2]. Some respondents also made the link between improving business efficiency and RFID: ‘the business was not good at moving stock around the organisation, we needed better data’[R4]. But they were very clear that RFID in and of itself was not the panacea, it was merely a potentially powerful tool to enable change in the business through providing new data points to identify weaknesses and inefficiencies, and review interventions.

"operating on line is tough – it is very easy to get it wrong and lose customers"

The Omni Channel Imperative

Write large across all the initial discussions about the reasons for starting out on a RFID journey was its enabling capacity to help businesses develop and deliver a more profitable omni channel consumer experience. As one respondent clearly articulated: ‘there was an acceptance in the business that stock accuracy was crucial to the development of the business, based on the desire to move into omni channel – pick from store, intelligent stock distribution, accuracy in buying, accuracy in stock levels and a seamless view to both customers and staff of stock’[R7]. Other agreed: ‘the move to omni channel was also a key driver. This is why RFID would be part of the future of the business’[R1]; ‘our long-term vision was that we knew we needed to improve our inventory accuracy to turn on our omni-channel programmes’[R1]. The critical role of RFID in helping to improve the visibility and accuracy of stock files was particularly apparent in many of the comments made by respondents: ‘it also fits our strategic ambition of omni channel which is about visibility of product to customers across the estate – online and in branch’[R5]. Put simply, if there are significant levels of inaccuracy in an inventory system, it becomes highly challenging to offer any form of online experience/pick up in store service that is going to consistently and satisfactorily meet the wishes of increasingly demanding consumers.

"the move to omni channel was also a key driver. This is why RFID would be part of the future of the business"

Previous History of Using RFID

Many of the companies taking part in this research had a track record of trying out the technology in the past, which often influenced their decision to subsequently invest. As detailed earlier, RFID has had a chequered history within retailing, initially over-promising and subsequently languishing as inflated expectations faded into the stark realities of still evolving immature technologies and hard to achieve returns on investment.

"the business was not good at moving stock around the organisation, we needed better data"

Some respondents had been part of that early journey: ‘… [we] couldn’t get it to work – the cost was prohibitive and the technology was not reliable enough’[R5]; ‘our previous efforts failed due to cost and technical issues’[R2]. But, it also meant that as the technology matured, and the business case become more attractive, these company’s previous experiences (where the organisational memory was maintained) enabled them to move forward incrementally and with a fair degree of studied circumspection. For those that had not tried the technology before, most were aware of the previous challenges and had felt that the positive momentum within the RFID industry, particularly around pricing and notable improvements in the reliability of the technology, made it the right time to initiate a trial.

"everything is possible, but it comes back to the cost and the benefit it can bring to the business"

The Role of the Board and Recognising the Financial Realities

For virtually all of the companies contributing to this research, the role of the senior management team in both the initiation and subsequent delivery of the RFID project was paramount: ‘[the] initiative came from the Board20. High initial costs required a strong business case and ROI – could only happen with full Board support’[R2]. This is perhaps not surprising, given the not inconsiderable upfront investment and business changes required to make it work: ‘everything is possible, but it comes back to the cost and the benefit it can bring to the business’[R3].

For some, senior management positively championed the idea: ‘it came directly from the Board, top down’[R2], while for others the senior team were more watchful: ‘introduction of RFID was more evolutionary than revolutionary – interest from the Board that matured into a business case’[R7]. In only one case was the drive for using RFID from the bottom up but even then, the support of the Board was still key to getting the project moving forward. In many respects this is not unexpected; most if not all RFID projects will span across virtually all elements within a modern retail business and so achieving cross functional buy-in inevitably will require decisions made at the highest level of the organisation. Above all, however, all respondents recognised the critical importance of identifying the financial imperative – ‘it needs to be a sound investment and not just a nice to have technology’[R6]; ‘they [the Board] will always want to know how much is it going to cost and what will we get out of it?’[R5].

"it needs to be a sound investment and not just a nice to have technology"

The Business Context

While the research interviews elicited many different contexts within which the decision to invest in RFID was made, most had the same core driving imperative: how can the business evolve to remain competitive through continuing to delight the consumer in ways that are both efficient and profitable? Improving the visibility of merchandise across the retail environment was viewed as a key factor in enabling this to happen – in many respects, it was seen as the glue that will increasingly hold together much of the architecture of 21st Century retailing. How that visibility will be realised is still an open debate and will no doubt be achieved through a myriad of technologies and processes, but for the companies taking part in this research, their business context made an investment in an RFID system something worth pursuing.

Getting Started on an RFID Journey

The following sections of this report are written with the prospective RFID retail user in mind, mapping out the various steps taken by the case study companies on their journey to using RFID in their businesses. This first section focusses upon how they started their journey – who was tasked to lead the initiative, how and why it was important to engage the rest of the business with it, where they sought help and how they went about choosing the technology they decided to use. This is then followed by sections continuing the journey: the process of undertaking a trial; how they went about measuring the impact of RFID and what they found; and then subsequently how they went about rolling out the technology across their businesses.

Choose a Business Leader

As with all change projects, it requires a leader to drive the initiative forward. For the companies taking part in this research three approaches were adopted. For some, the scale of the project necessitated the establishment of a new business unit, with a leader and support staff drawn from other areas, based upon some existing established expertise considered relevant to the initiative.

For the majority of the case studies, a leader was identified within the business unit largely responsible for operations (the exact title varied between companies, such as Retail Operations, Operations or Sales Support). In two cases, a third approach was adopted: the project leader was based in the loss prevention function.

While the first two approaches are largely self explanatory, drawing leadership from within loss prevention teams may seem an unusual approach to adopt given the overarching objectives set out by most of the companies introducing this technology. Partly it may be attributable to RFID being associated with ‘tagging’ and the loss prevention function being historically responsible for another form of retail tagging: Electronic Article Surveillance (EAS). But, for one of the two case studies, it was more to do with how the company defined the parameters of responsibility for the loss prevention team, in this case holding them accountable for stock integrity.

In the other case it was more about the RFID initiative coming directly from the loss prevention leader and this person very much taking the initiative on an ad hoc largely unplanned basis. Other than the last case, the common denominator is that leadership for the project typically came from whoever had/or was given responsibility for onshelf availability/stock integrity, which, as discussed in the previous section, is a major business driver for thinking about investing in RFID. Even in the loss prevention-driven case study, the view now seems to be that the future roll-out and ownership of the initiative should be moved away from loss prevention and into the function responsible for store operations.

Engage the Business

As mentioned previously, RFID projects by their very nature, develop long tentacles spreading out across entire retail organisations: ‘… it touches the entire business’[R7]; ‘every function was involved in the project – buying, production, logistics; it was very important to have all functions represented’[R3]. Respondents to this research clearly articulated the importance of working hard at getting cross functional buy in to their RFID project: ‘there was a lot of education [of the rest of business] needed on the benefits of RFID technology – [it] wasn’t clear to the rest of the business what a change it would bring along’[R10]. At least one of the companies used stakeholder analysis21, a very common but valuable business tool, to identify who should be involved and to what degree there may be resistance to its introduction: ‘[we] used stakeholder analysis to identify all our key players in the business and how they might feel about being involved in a project’[R4]. Indeed, it should not be assumed that everybody will be immediately supportive of the project: ‘people were nervous about introducing this technology and whether the resource was available to deliver it’[R3]; ‘[the] rest of the business was largely positive – some pockets of resistance’[R2].

A group that was considered particularly important to engage in the project, especially when it begins to roll out more broadly across the organisation and become part of business as usual (BAU), was the Buying function: ‘Buyers have to be on board very early – [for us] nine months before the product enters the supply chain’[R4]. For the most part, the case-study companies did not experience much resistance: ‘thought it would need a really strong buy in from the business but actually the complete opposite, IT very early on saw the benefits and wanted to integrate – the whole organisation has embraced the initiative’[R7].

Approaches to raising awareness varied considerably between companies: RFID open days, store mock-ups in Head Quarters showing how RFID would work, cross functional briefing events and so on. But all agreed that in the early stages of the development of the project, getting the rest of the business not only aware of what RFID is and its potential, but also clearly articulating what the responsibilities of other functions are going to be was vitally important. In this respect, active support from senior management was considered key; they not only sign off on the required expenditure but can also generate the requisite organisational leverage to ensure key players are engaged.

'the rest of the business needed educating on the benefits of RFID Technologies"

Seek External Help

Virtually all of the companies taking part in this research sought some degree of external advice as they began their RFID journey, although it varied considerably in the degree to which it was formalised. Three approaches were evident: employ the services of a RFID specialist consultancy; rely upon the advice available from the chosen technology provider; and finally, reach out to other retailers who had already embarked on introducing RFID into their businesses and organisations that have developed standards such as GS1.

Numerous RFID consultancies are now available and two of the case-study companies made use of their services to varying degrees. Some of the services provided included: advice on which technology to select; drawing up procurement documents; developing the business case to be presented to the Board; carrying out reviews to understand the size of the problems that RFID might address; overseeing implementation of a trial and roll out; and measuring impact. Clearly there is a cost associated with this approach, but for those using this service, it was regarded as a sound investment, especially where organisational knowledge on the topic was limited.

Another approach is to rely upon the experience and knowledge available from the one or more of the technology providers selected by the business. For most of these providers, this will not be their first RFID project and so they will often have a wealth of experience to offer, particularly in terms of the practicalities of delivering RFID in a retail environment. The obvious concern with this approach is that these companies may well have a vested interest in the advice and choices they present, which may not always be the most advantageous nor appropriate for the retail client.

Finally, the majority of respondents suggested that they reached out to other retailers for advice, mainly through attending trade shows and conferences and/or through personal contacts. A number of retail companies have been very active in the RFID sphere for some years and regularly present at conferences such as RFID Live22. These presentations, while often only ever able to provide overviews of the approach to adopt and the pitfalls to be aware of, can be extremely useful, particularly in terms providing access to a company representative that can be contacted after the event. A number of companies had also made use of the information made available by standards bodies such as GS1 that regularly provide conferences and have built up a considerable knowledge base on how to utilise RFID technologies23.

Whatever approach is adopted, virtually all of the respondents recognised the value and importance of seeking help from outside their own organisation – initiating an RFID project can be a daunting project, especially when the capital outlay can be considerable, and the technology choices are many and varied.

Choose RFID Technologies

One of the main reasons why the RFID euphoria in the early to mid 2000s quickly faded away was the realisation that while the concept it promised was genuinely revolutionary (transparency of all merchandise throughout retail supply chains, checkout less stores, the end of retail crime etc.), the reality was very different, mainly due to the immaturity of the technology necessary to deliver it. Early adopters, some of whom took part in this research, ran into too many issues around reliability and cost. This next section looks at some of the decisions made about the choice of technology used but it is important to stress that it is not a review per se of any given technology nor its provider – it is not the purpose of this report to provide a technical review. The first part looks at choices made around tagging technologies while the second part focusses upon the other technologies used to both read them and make sense of the ensuing data.

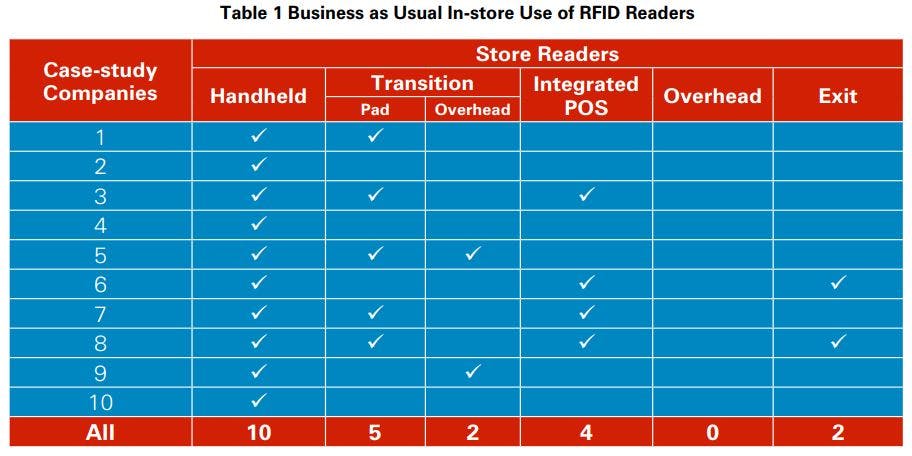

It is worth noting that, for most of the companies taking part in this research, the approach adopted to developing their RFID ‘system’ can be best described as circumspect, cautious, modest and highly price conscious. The majority of systems reviewed by this research are relatively simple using just a few technologies. Most rely mainly upon handheld readers used by store staff to capture RFID data and none have invested in overhead readers beyond some experimental trial stores.

Some have invested in transition readers to capture data flows between different parts of the supply chain and zones in retail stores, but not many.

Moreover, one-half have yet to fully integrate a read capability into their POS systems and properly resolve the thorny issue of data integration with existing inventory systems (something which will be discussed later in the report). As one respondent put it: ‘we only have handheld readers, nothing else. No connection with till, no front or back readers’[R4]. In many respects this was both surprising and refreshing: surprising because media hype often tends to suggest we are entering a retail future of startling technological complexity akin to a Minority Report landscape, much of which will be delivered by objects communicating with each other and various systems at all times. But it was also refreshing because most of these companies had built a successful business model, with verifiable Returns on Investment (ROIs), mostly focussing upon fixing often only one issue and doing it with the minimum of technological investment. The overarching philosophy for most of these companies when it came to developing their RFID programme was focussed pragmatism driven by financial probity – keep it simple and make it pay

"the overarching philosophy was focussed pragmatism driven by financial probity – keep it simple and make it pay"

Consider Hard, Soft (Swing) or Sewn-in Tags Choices

One of the technology challenges in the early to mid 2000s was the manufacture, supply and application of RFID tags that were sufficiently reliable and financially viable for a retailer to purchase on a large scale24. For this group of retailers, the issue of tag reliability did not seem to be an issue of concern anymore: ‘never found a tag that didn’t read’[R4]; ‘had so few tag failures that we stopped checking and recording them’[R3]. Indeed, one respondent offered some data on the extent to which their chosen tags were actually performing better than traditional barcodes: ‘had only 20 errors with tags not correctly set up out of 1.5 billion products; with barcodes it was 1.5% and with RFID tags it is 0.003%’[R8]. Other respondents were of the same view in terms of the reliability of the tag but did highlight associated issues that were more of a concern: ‘tag quality is not the problem anymore – [tags] falling off is more of an issue to us’[R2]; ‘[it is] not about reliability of the tag per se, more about where it is positioned and affixed and whether it is on the product at all’[R6].

Virtually all of the respondents to this research had opted for a combination of swing and sticker tags, with only one initially utilising a hard tag variant although they too are now planning to use swing tags and stickers as the initial approach was deemed impractical in the planned roll out phase. The decision to use this type of tag was driven mainly by pragmatism – they offered the most straightforward approach to application in the manufacturing process. All respondents bar one had opted very early on in their RFID journey for source tagging at the point of manufacture – it was deemed the most sustainable and costeffective way of applying them: ‘for us, source tagging was the only way we could make this work in the long term – DCs are too busy and stores are not reliable enough to do it consistently, especially at busy times’[R3].

Some companies had considered the extent to which the tag could and should be incorporated into the merchandise, such as being sown into the care label, but this raised two main concerns associated with privacy and practicality: ‘didn’t want to sow into garment for privacy reasons and worries about the impact of the manufacturing process on the tag[R2]; ‘we did not want the company associated with any issues relating to privacy and data protection … it would also impact upon the look and feel of the product’[R3]. However, two of the case-study companies viewed greater integration of the tag as a critical next step in their RFID journey, principally to deal with the ongoing problems of accidental and malicious removal of the tag.

It was very apparent that most of the companies had taken a considerable amount of time to test and refine the design and positioning of the tag and at which point in the manufacturing process it should be applied. For some of the larger users (in terms of volume of tags purchased and range of SKUs being tagged) they had established teams to advise on tag location and design, including developing detailed guides for suppliers on how the tags should be applied. The key message was that in order for the RFID project to be successful, the impact of all supply chain processes on the tag, the way in which particular products will impact upon tag performance, and where the tags will be read, needed to be carefully researched and documented.

Finally, views differed on the extent to which retailers should be utilising one or more tag suppliers. Some had opted for more than one supplier to reduce risk and increase competition while others regarded this as too complex to manage and instead preferred to use only one provider. Clearly, there is no right or wrong answer and the decision will come down to any given company’s appetite for risk and ability to manage complexity in their supply chain.

Reader Technologies

As mentioned earlier, most of the case-study companies had adopted a relatively straightforward and arguably simplistic approach to how they went about capturing RFID-related data within their businesses, driven by the realities of their own retail environment, organisational ambition and budget. The 10 case-study companies had experience of a combination of five different forms of readers to enable them to capture RFID data at different locations and points in the retail process: Handheld Readers/Wands; Point of Sale (POS) Readers; Transition Readers (overhead and fixed stations); Overhead Readers; and Exit Readers (Table 1). By far the most common were Handheld Readers/ Wands, which were employed by all of the companies and were provided to store staff. There were used to perform a number of tasks including regular stock counts both in the front and back of their stores and receiving stock deliveries.

Each chosen Handheld Reader/Wand technology had varying degrees of functionality although giving the user statistical awareness of the number of products they were aiming to scan and/or their progress towards reaching the required product recognition target was considered very important. Indeed, one respondent highlighted the operational necessity of doing this: ‘we needed to get [store] staff to understand to work to the [company SKU] target rather than 100% – 100% accuracy generally costs too much money to achieve in terms of productivity’[R2]. In this example, overly assiduous store staff were considered to be spending too much time seeking a ‘perfect’ SKU score when the added value to the business of achieving this was less than the cost of the time it took to deliver: ‘[it is] important to remember that it is not about getting 100% accuracy, the goal is to meet the aims of the project – improve on where we were which was nowhere near 100%!’[R6].

The next most common form of reader in use was Transition Readers – either a fixed pad/device, usually at the back of the store, that staff could use to manually register RFID-enabled merchandise, or overhead devices that automatically recorded when tags moved through their read field. For those companies using this technology, the primary purpose was to better understand where stock was located, principally in the front or back of the store. As will be discussed below, one of the key drivers of lost sales is stock not being moved in good time from the back of the store to the sales floor, generating what some retailers describe as Not on Shelf But On Stock (NOSBOS) events – lost sales not because the store does not physically have the merchandise but that it is not in the ‘right’ place at the ‘right’ time to enable a customer to purchase it.

Only two of the 10 companies were using overhead transition readers, with one-half using fixed readers/ pads, which require staff to manually transition/ record stock as it is moved from one place in the store to another. As will be discussed later, RFID systems typically work best when the amount of human interaction in the data collection process is kept to a minimum, and so overhead readers would seem a better option. But, all of the companies that were either using overhead readers or had tested their use, had significant concerns about their reliability and cost effectiveness: ‘we asked ourselves, do we really need overhead readers – do they work well enough and will they deliver enough to justify the cost?[R3].

Less than one-half of case-study companies had currently invested in some form of integrated RFID Reader at the POS whereby a member of staff was able to either scan/read the product tag just once as part of the customer purchase transaction. As will be discussed below, this point of integration has generated the greatest difficulties/challenges for many of the companies taking part in this research, not least because of complexity and scalability issues, and associated costs: ‘would love to link to EPOS at some point but considerable cost involved’[R6]; ‘we looked at this [linking to EPOS system] but a lengthy project would be required – would require 23 different systems to change to make it work’[R2].

"we looked at linking to EPOS but it would require 23 different systems to change to make it work"

Where companies tried a compromise arrangement at the POS, such as a separate RFID reader, recording accuracy became an issue: ‘every day [staff] missed between 3-6% of tags despite all best efforts’[R5]. Another user had found a similar error rate: ‘getting a read rate of 90% to 95% at the checkout’[R9]; and a third found a similar rate in their trial period that persuaded them it was not a longterm option for them: ‘had [RFID] pads at POS but only got 80% read rate. We realised had to go for integration at POS’[R10].

As can be seen in Table 1, no case study company had rolled out any form of fixed overhead reader technology as this stage, although one company was currently undertaking a concerted trial to understand whether they might be a viable option for some of their retail environments in the near future.

A number of the other companies had explored the possibility of using fixed overhead readers as they potentially offer an exciting extension to an RFID system, effectively removing the need for staff to carry out any manual scanning of tagged merchandise, which would lead to considerable staff productivity savings. But, most were of the view that it was currently impossible to achieve a ROI on this technology:

we cannot make the finances stack up. We reckon the pay back was 13 years but [could be] up to 26 years for large stores – just not going to fly[R9]; long way to go with fixed readers but they will be there in the future[R2].

Where the technology was being trialled, impressive read rates had been observed but it was still questionable as to whether either a subsequent sales uplift due to greater stock accuracy and/ or reductions in staff costs would warrant the investment.

In terms of reader technology at store exits, two companies were using this technology across their retail estate and others had tested them but they had also come up against issues of read accuracy: ‘a high percentage of [our] products have a metal component so exit reads were poor – stops them [Exit Readers] getting a really clean read[R10]; ‘we have exit antennae but we have had problems with them – if people walk too fast or it is windy or people have bags – only getting 70% read rate at the exits’[R3]; ‘we are getting 85% accuracy at the readers at the exits’[R8]. we looked at linking to EPOS but it would require 23 different systems to change to make it work Measuring the Impact of RFID in Retailing

As will be discussed later, when the issue of RFID and Loss Prevention is discussed in more detail, with the RFID technologies currently adopted by these case-study companies, getting a reliable read rate at exits clearly remains a challenge and may explain why few currently regard RFID as a viable store security intervention.

RFID Software Systems

The final piece of the ‘technology’ picture25, is the use of a software system to record, assimilate and, where possible integrate, the RFID data generated by the various readers as they capture the presence and movement of RFID tags in the retail supply chain. There was a broad range of providers used by the companies taking part in this research, chosen for a host of different reasons including: previous experience, perceived compatibility with existing systems, price and recommendation. The integration of RFID data with existing systems has proved to be one of the biggest challenges these companies have faced: ‘the integration issue is still the problem – still a lot of noise’[R10].

Understanding how any proposed RFID software system will not only meet the objectives of the programme, but crucially work with the current business systems was something most companies struggled with and continue to try and address: ‘we didn’t think this through enough when we started and in hindsight we would have chosen a different piece of software, but we are where we are’[R3].

Starting an RFID Journey

For most of the companies taking part in this research their RFID journey began with an understanding of a problem that needed to be resolved and a recognition of the importance of gaining cross-functional support from the business. It was also clear that many of them had worked very hard to develop a good understanding of how a RFID-based system might interact within their given business context and how this would affect the choice of technologies to be used. Much of this learning came from undertaking various types of trials and it is to these experiences that we turn to next.

Undertaking a Trial

Perhaps not surprisingly, given the potential cost and impact upon the business, all the companies taking part in this research had undertaken or were continuing to undertake various forms of trials to better understand what the value of investing in an RFID system might be and how it should be designed to work most effectively within their organisational eco system. While the participating companies all adopted different ways in which to trial RFID, some common themes can be identified, not least the use of feasibility studies or proof of concept trials, followed up by more detailed pilot studies and then development trials.

Proof of Concept Trials

While some of the case-study companies had used RFID technologies in the past, all felt that it was important to start out with relatively small-scale proof of concept trials to understand at a basic level, whether the proposed technologies would actually work in their environment. On average this was undertaken in about 3 stores, usually on just a few SKUs and was designed to keep store disruption to a minimum.

At this stage, most companies simply opted to apply the RFID tags either at one or more of their own Distribution Centres (DCs) or in the participating stores, with responsibility for gathering data undertaken by the project team rather than store staff. Above all, these types of trial were mainly about simply understanding whether various types of RFID technology would actually work or not and whether they should be used in any subsequent pilot trial: ‘tried Portals between back of house and shop floor but didn’t have high read rates and [so we] abandoned that option’[R5].

While the period of time for these types of trial varied considerably between the companies, most were relatively short, in the region of about 3 months, not least because of the cost and effort involved in undertaking them. It could be that in the future, as the technology continues to improve and previous concerns about the reliability of the technology fade (as has been found in the case studies presented in this study), then Proof of Concept Trials may become less necessary and prospective users are able to begin their RFID journey with Pilot Trials, skipping this technology verification step.

RFID Pilot Trials

After this initial feasibility testing, companies typically embarked upon more detailed trials to try and answer the following questions:

- To what extent will RFID deliver the proposed improvements in agreed KPIs and achieve an ROI?

- How well or not will the technology work in various retail settings?

- How will RFID operate within current business processes and what would need to change?

- How will staff respond to and use the technology?

- What needs to be put in place to ensure any future roll out will be sustainable and successful?

Different companies adopted different approaches to how these trials were carried out with some lasting many years while others were remarkably and perhaps regrettably short:

Had to resolve the process-related issues in the [pilot] stores and 2 months was not enough time … [store] staff felt overwhelmed by everything – using different systems; the technology was completely new to them; they didn’t understand the unique identification of all products – [it was] hard to explain why this mattered given how they had viewed stock in the past; [they] felt like [it was] more work not less; couldn’t see how it would help them[R8].

For others, the approach adopted was much more incremental, designing the pilot phase to identify whether the RFID system would deliver the planned improvements in KPIs across different retail settings and how it would impact upon the business: ‘[we] needed to systematically and rigorously understand the people and process elements of the business and how they will be impacted and or respond to the use of RFID’[R8].

One respondent described how they gradually ratcheted up their trial programme to fully test the potential impact of growing levels of retail complexity: ‘we started with just a few small stores with average levels of historical stock accuracy where we did all the counting …[then] we progressed to stores where the staff did the counting … [then] moved on to trying it in bigger stores with more complex spaces, such as remote stock rooms and multiple levels’[R9].

For 9 out of the 10 case studies, an early decision was made that source tagging at the point of manufacture was the only feasible way in which RFID could be rolled out across the business and so many of the trials were designed with a temporary and unsustainable tagging strategy in place, which invariably impacted upon the scale, timing, length and location of the trials: ‘the DCs did struggle to support the trial’[R8]; ‘we had entire teams in the DC just tagging’[R5].

"for most companies it was decided that source tagging at the point of manufacture was the only feasible way in which RFID could be rolled out across the business"

As detailed in the previous section, a number of the technological issues that plagued previous RFID trials carried out in the early to mid 2000s have now been addressed to a fair degree and so a significant proportion of the learning in the trials was more about understanding how RFID would assimilate with business processes and be understood and used by store staff: ‘the process and people parts were the hardest – complex processes and infrastructure in the business … [we] needed to systematically and rigorously understand the people and process elements of the business and how they will be impacted and or respond to the use of RFID’[R8].

"the process and people parts were the hardest ... we needed to understand how they will be impacted by RFID"

Some retailers also used pilot trials to prepare the business for a future roll out of RFID, in particular how staff would be trained to use the system and suppliers would be advised about tag application. As will be discussed below, rolling out RFID programmes across large and complex retail organisations can be challenging and for some businesses, the pilot phase enabled them to work through what some of these challenges might be and how they might best be resolved:

this [trial period] was less about checking the technology and more about checking the quality of the roll out materials – the viability of the distance learning pack, the tagging guide, how to use the equipment and so on. We were not going to use face to face training, it was all going to be online and so we needed to test it would work[R9].

Given that all 10 companies taking part in this research have moved to roll out RFID across their organisations, it can be argued that their trial process was successful – it enabled them to generate evidence to support the financial case for RFID, identified what the impact on the business was likely to be, how the system had to be designed to fit within existing systems and processes and what the limitations of the technology were within a given context: ‘trials went pretty much as we expected … our worst fears were not realised – tags didn’t fall of as much as we thought they might!’[R7].

Development Trials

For many of the companies in this study, the roll out of an RFID system across their business is a significant but also incremental step in their RFID journey – a number continue to test new ideas and technologies to see how the original system can be built upon and enhanced.

As mentioned previously, most of the RFID systems rolled out by the companies covered in this research might best be described as modest – currently almost exclusively store-based with data capture mainly reliant upon the active involvement of store staff and many integration issues yet to be resolved. But all see this as a viable and sustainable (financially at least) model upon which to build future iterations. As such, some companies continue to carry out developmental RFID trials such as testing the use of overhead and transition readers, ways to better integrate the data with existing systems, and new ideas concerning tag performance and applicability to a broader range of merchandise.

While RFID-based technologies will undoubtedly evolve further, it is likely that these companies will continue to experiment but only where there is a justifiable business case to be made – the financial prudence that embraces most if not all of the programmes studied by this research will not doubt remain a key driver of future developments.

"financial prudence that embraces most if not all of the programmes studied by this research will not doubt remain a key driver of future developments"

Measuring the Impact of RFID

For all the companies taking part in this research, the primary objective of investing in an RFID system was to improve their profitability by reaping various benefits delivered through having the ability to more accurately and effectively identify merchandise as it moved through their retail supply chains – from point of manufacture right through to the point of sale and sometimes beyond such as managing returns.

How this was measured and the ways in which RFID systems actually deliver these benefits varied considerably. As with any intervention, understanding the way in which Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) – the verifiable and agreed measures associated with the introduction of change, is frequently shrouded in rather confused and confusing terminology26. For instance, KPIs are metrics that actively measure specific, directly attributable, planned outcomes related to agreed goals, but they are often confused with other variables that are more concerned with measuring the performance of the intervention – in effect is it doing what it is supposed to do?27 One company considered the latter to be Key Performance Drivers (KPDs), measures of whether RFID operations are operating correctly and optimally, such as the reliability of tags or the success rate of Readers to identify them28. In and of themselves, they do not directly contribute to the delivery of a project goal – they are measures of system efficiency and reliability and not indicators of the consequence of introducing an intervention.

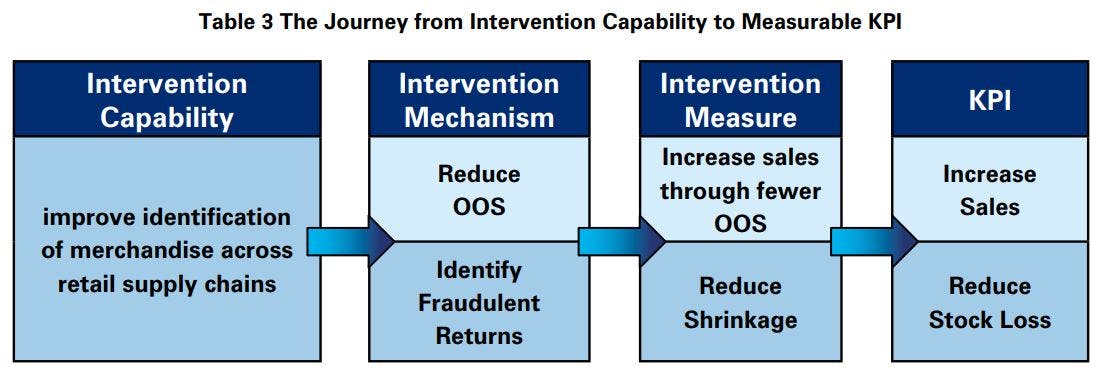

It is also important to understand the ways in which KPIs are actually delivered within a business context and how these are measured. For instance, the goal of introducing a technology such as CCTV may be to reduce crime and make people feel safer. The KPIs might therefore be levels of certain types of crime and public perceptions of feeling safe and secure. But understanding how CCTV will actually deliver any difference in these KPIs needs to be understood – the ‘Intervention Mechanisms’ and how these are converted into ‘Intervention Measures’ have to be clearly articulated. For instance, crime will not be reduced simply because a camera has been installed on a pole in a public street – in and of itself it has no impact – it cannot leap off its pole and arrest a thief! But, crime could be reduced because would-be offenders who see the camera may now feel it has become too risky to commit crime in that area because they feel they are more likely to get caught. It may also be the case that crime goes down because more offenders get caught because the camera operator is able to raise a physical security response to a crime scene and the offender is arrested, subsequently incarcerated and can no longer commit any further crimes for a period of time. In the first instance, crime will be reduced because offenders are less likely to commit crime in that location and in the second instance, crime will be reduced because there are fewer criminals around to commit crime. Either way, understanding how an intervention will trigger mechanisms that will in turn deliver changes in KPIs is vitally important to understand if they are to be designed and managed effectively.

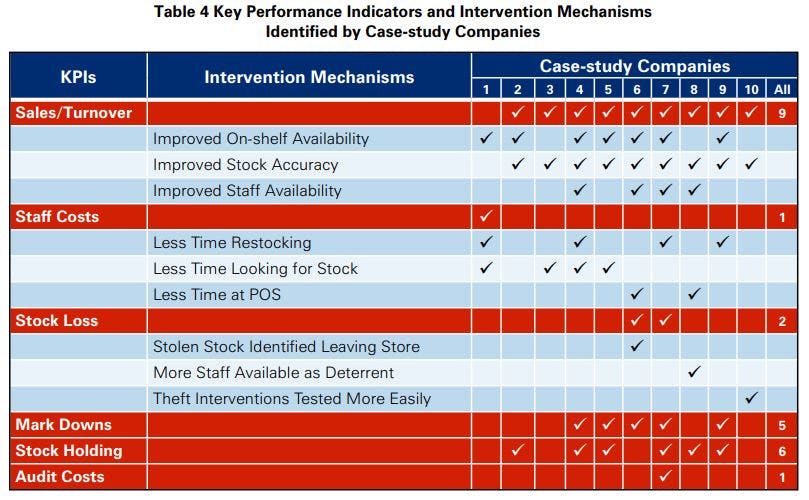

Outlined below in Table 2 is a summary of the KPIs and associated Intervention Mechanisms and Intervention Measures that could be identified across the 10 case studies taking part in this research. It is important to stress that it is an aggregation of all the companies – none made use of all the KPIs detailed nor described all the associated Intervention Mechanisms and some are based upon the researcher extrapolating from the comments made by those interviewed. It is also not intended to be an exhaustive list of all the possible KPIs, Mechanisms and Measures that could be associated with the use of an RFID system.

"understanding how various interventions trigger mechanisms that will deliver changes in KPIs is vitally important to understand"

Key Performance Indicators

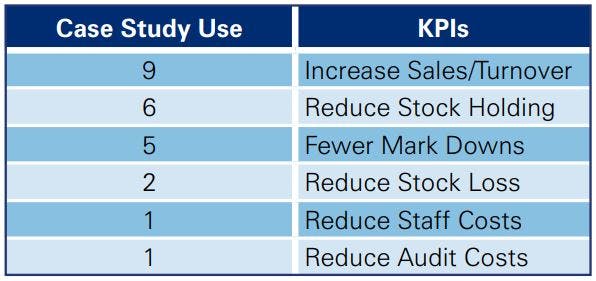

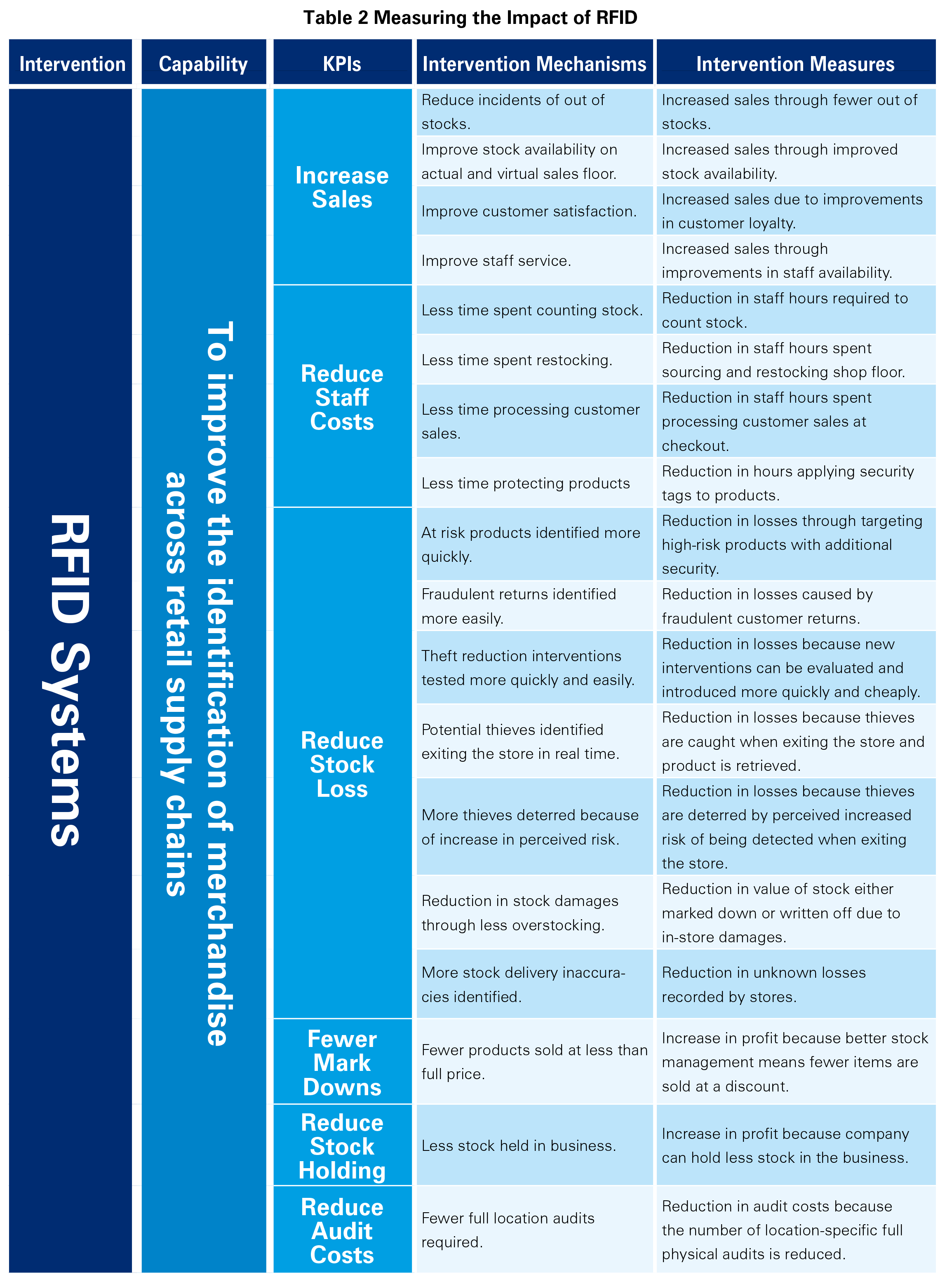

The research identified six key metrics used by the participating companies to measure the impact of using RFID systems:

By far and away the most popular measure used by the case-study companies was the impact upon sales/turnover – 9 of the 10 companies explicitly measured the impact on this metric. For some it was the only metric that was used and as will be seen below, a relatively modest improvement was more than sufficient to generate a satisfactory ROI: ‘for us, only one KPI: increased sales … which is driven by stock integrity, generating accurate replenishment’[R4] . The second most popular measure was the capacity for RFID to enable businesses to reduce their stock holding without have any adverse impact upon their operations. The biggest cost to a retailer is the purchase of stock and so developing the capacity to reduce the amount of merchandise within a business clearly has the potential to produce significant financial benefits.

The third most used KPI related to the extent to which RFID could reduce the amount of stock that was sold at a discount. One of the great challenges of retailing is ensuring that the right stock is in the right place at the right time because this significantly increases the opportunity to achieve the desired price. When this does not happen, particularly with highly seasonal and/or promotional products, inevitably price discounting has to take place to ensure some value for the stock is achieved. Because RFID can significantly help to minimise this margin-erosion problem, it is understandable why this was a KPI for many of the companies taking part in this research.

The remaining three KPIs: reducing stock loss, staffing costs and audit costs were much less frequently used by the case-study companies – only two had some form of measure for stock loss and only one had a KPI for staff saving and audit costs. In terms of stock loss, as will be discussed later in this report, most companies did not believe that their RFID system, as currently configured, had much prospect for dealing with most forms of malicious stock loss – the tags were too easy to remove and the exit reader technology was either absent or deemed to be too unreliable.

While only one company actively sought to measure the value of introducing RFID to reduce staff costs, a number of other companies recognised its ability to do this in the future and as can be seen in Table 4 below, a significant number had ‘banked’ RFIDenabled staff time to help deliver improved sales through better customer service and engagement. Finally, only one company had reached the point where they were able to measure the impact of using RFID on reducing the cost of physical stock audit. However, a number of other companies suggested that this was certainly something that would accrue to them over time as their RFID systems bedded down and accounting and auditing practices began to understand and accept the use of data derived from these systems.

Intervention Mechanisms

As detailed above, RFID in and of itself cannot deliver KPIs – it is merely a technology that generates data that can then be used to enable changes or mechanisms to be triggered, in this respect, it is a facilitator technology. It is also worth noting that Intervention Mechanisms can be both positive and spaces can lead to the displacement of crime – crime is not reduced, it is simply moved to another location.

The case-study companies also varied in their ability to measure these mechanisms – some are inevitably much more tangible and amenable to measurement than others, such as levels of out of stocks compared with improved customer satisfaction (Table 4 below lists those that were measured). It is also worth noting that while the overarching KPI associated with one or more Intervention Mechanisms was not actively measured by a company, some still considered the underlying mechanisms as being part of their RFID programme. For instance, while most did not have a KPI for a reduction in staff costs, some recognised that RFID delivered a staff time benefit that could be utilised to enable another KPI such as an improvement in sales or a reduction in stock loss.

As can be seen in Table 2, it was possible to begin to identify, for each of the KPIs used, the Intervention Mechanisms that can be associated with the case-study companies taking part in this research. It is important to note that this list of Intervention Mechanisms is not necessarily complete – it is merely those that were gleaned from the data collection process for this research.

"RFID in and of itself cannot deliver KPIs – it is merely a technology that generates data that can enable change"

Increase Sales

Four Intervention Mechanisms were associated with this KPI: reduced out of stocks, improved stock availability, improved staff service and increased customer satisfaction. The link to improved sales for the first two is relatively straightforward – if the right stock is not available on the shelves for customers to buy then clearly sales will be impacted. As detailed below, some companies were able to share data on the way these mechanisms were affected by the introduction of RFID. The latter two mechanisms are rather more tangentially linked to increased sales: by reducing the amount of time staff had to spend auditing merchandise and restocking, RFID had enabled staff to potentially spend more time on the shop floor assisting customers and encouraging sales.

It was also the case that by ensuring more customers were able to purchase the products they wanted at the right time and place (because RFID had enabled better stock accuracy both in stores and online), then they may be more inclined to shop with that retailer in the future and hence increase sales.

Reduce Stock Holding and Fewer Mark Downs

For both these KPIs, only one Intervention Mechanism was apparent for each of them – the reduction in the amount of merchandise held by the business, either overall or in particular locations, and the amount of stock sold at a discounted price. While the former measure was thought to be relatively easy to calculate, the latter often required fairly detailed analytics to extract the value added offered by RFID.

Reduce Stock

Loss While as a KPI it was used by only two companies, the complexity of the issue generates the most number of Intervention Mechanisms of all the KPIs found in this research. In terms of shop theft (assuming the tag remains on the product and can be read by a reader), two mechanisms can be triggered: thieves leaving the store can be identified and stolen product recovered (assuming there is a human response available); and thieves are more likely to be deterred from trying to steal because they become aware of the potential of the system to facilitate their detention. In addition, fraudulent returns are potentially easier to identify (assuming the original tag is still attached to the product) because the EPC associated with the returning product is capable of establishing whether it has been purchased in the first place.

Case-study companies also identified other potential Intervention Mechanisms associated with reducing stock loss, including better identifying those products more prone to theft (which could then be better protected with other forms of security) and being able to test loss prevention interventions more quickly and easily. Historically, testing the impact of loss prevention interventions has been notoriously difficult, principally because getting reliable and verifiable stock data before, during and after the intervention has been introduced has been neither easy nor cheap.

With the introduction of RFID and associated regular, frequently weekly stock counts, loss prevention managers can now potentially test loss prevention interventions much more quickly and have access to much better data to understand their impact.

Two Intervention Mechanisms were associated with having an impact on non-malicious forms of loss: a reduction in damaged products that are either not possible to sell or must be sold at a reduced price (because of an associated KPI – Reduced Stock Holding), and greater visibility of stock delivery errors. For the former, typically, if retail stores have less stock, then they are much less likely to damage it – store rooms are easier to manage, product is sold through more quickly and so on. For the latter, gaining greater visibility of actual stock deliveries to stores can positively impact upon levels of unknown stock loss (shrinkage), particularly where stock can be shown to have not been delivered or the wrong stock has been sent.

Reduce Staff Costs

While only one company used this KPI, a number of companies pointed to the use of some of the associated Intervention Mechanisms as valuable outcomes of using RFID, and which enabled other KPIs to be delivered. Most common was the saving associated with the amount to time staff had to spend restocking as a consequence of RFID – it enabled staff to have much better visibility about not only what needed to be restocked but also where it was located in the backroom area. Similarly, a number of companies pointed to the significant time savings they had accrued because staff could now count stock so much more quickly, mainly using the hand-held scanners provided.

Two other mechanisms were identified – less time required to process customers at the point of sale and less time required to apply security tags. In terms of the former, one company in particular had undertaken detailed analysis to understand the value of this saving, while for the latter, this was obviously only the case where RFID was seen as a replacement to an existing security technology such as EAS, or had enabled a more nuanced and selective approach to the number of products having an EAS tag attached to them.

Intervention Measures

While Intervention Mechanisms provide stepping stones between an intervention’s capability and its associated KPIs, there is also a need to understand the way in which potential Intervention Mechanisms should be measured to enable the KPI to be achieved. Table 3 provides an illustration of how each of the identified Mechanisms have a related Measure. For the most part, these are relatively straightforward.

What is important is to identify how any given Intervention Mechanism may be measured, although it is recognised that for some this may prove challenging and/or impractical to achieve as part of an RFID programme. In this respect, as found in this research, while companies may elect to identify only those Intervention Mechanisms and associated Measures that are possible to measure when building a business case, it may well be worth thinking through what some of the other more intangible outcomes of introducing RFID might be as these could be used as part of the overall business case.

Table 4 below summarises how the case-study companies varied in the ways in which they actively recognised the use of both KPI metrics and some of the underlying Intervention Mechanisms outlined in Table 2 above.

Measuring the Impact of RFID

While the case-study companies that agreed to participate in this research were prepared to share their experiences and detailed knowledge of using RFID-based systems, only some were willing to offer an indication of the actual results they had garnered from their use. This is not surprising given the sensitivity of some of the data and the growing view that successfully delivering RFID can be seen as part of maintaining a competitive edge in an increasingly challenging economic environment, particularly as omni-channel retail becomes more prevalent and important.