Video Technologies in Retailing

New insights on the use of video and video analytics in retail

Table of Contents:

- Foreword

- Executive Summary

- Introduction, Objectives and Methodology

- Current Utilisation of Video Technologies in Retailing

- - Delivering Deterrence

- - Undertaking Reviews

- - Carrying out Monitoring

- - Ensuring Compliance

- - Generating a Response

- - Providing Reassurance

- - Informing and Enabling the Business

- - Identifying, Detecting and Alerting: Video Analytics

- Assessing the Use of Video Analytics in Retailing

- - Defining Video Analytics

- - Promises and Current Realities

- - Examples of Video Analytics in Use

- - Challenges of Managing Video Analytics

- - Impact of Clarity of Purpose and Contextual Complexity on Video Analytics

- Strategic Trends in the Use of Video Technologies in Retailing

- - Ensuring Organisational Strategic Oversight

- - Delivering Cross Functional Use of Video

- - Growing Utilisation of Centralised Video Command Centres

- - Building Greater Capacity Through Data Integration

- - Business Requirements Driving System Design

- Summary of Findings

- Appendix 1: Methodology

- Appendix 2: Example Video Analytic Checklist

Languages :

This report, published in 2020, focuses upon providing a detailed and objective assessment of how and why video technologies are currently being used within the retail sector. In addition, it provides a critical review of both the potential and the challenges of utilising video analytics and the key strategic trends that can be seen in the retail industry.

It draws upon in-depth interviews with representatives from 22 retailers based in the US and Europe, with collective sales of nearly €1 trillion, equivalent to approximately 12% of their retail market, and operating in over 57,000 retail outlets. In addition, interviews were carried out with representatives from five major video technology providers.

The research summarises the way in which retailers currently use video technologies, grouping them into 8 use cases: Delivering Deterrence; Providing Reassurance; Ensuring Compliance; Undertaking Reviews; Informing and Enabling Business Decisions; Carrying out Monitoring; Generating a Response; and Identifying, Detecting and Alerting. It also describes some of the current ways in which video analytics are being used, focussed upon security and safety, and business intelligence applications. It offers a comprehensive review of some of the challenges of using video analytics in a retail environment, including issues around data accuracy, managing scalability, addressing bandwidth and processing concerns, difficulties of measuring and proving the ROI, and recognising the impact of contextual complexity and degree of clarity of purpose on video analytic performance.

The research concludes by bringing together some key strategic trends, including: the importance of developing organisational leadership in retailing on video technologies; ensuring that businesses focus upon delivering cross functional use, build greater capacity through data integration, and build video systems that meet organizational requirements.

Retailing is a constantly evolving and dynamic industry, hard wired into the economies of most countries. It is also an increasingly competitive and complex environment, demanding businesses to not only be agile and responsive to the needs of their customers, but also make use of a growing array of technologies. While video systems have been used by retailers for some time, primarily to deliver security and safety, this report provides a stimulus to think more creatively now, and in the future, about how its role can be further developed to enable retailers to meet their core goals of satisfying customers and returning a profit.

Foreword

The ECR Retail Loss Group is delighted to have had the opportunity to support this important and ground-breaking study. As a technology, CCTV has been a part of the retail environment for very many years – we are all very familiar with seeing it in retail stores and increasingly in many other settings as well.

However, longevity and ubiquity do not always translate into rationality – as an industry, we have not always been good at developing a clear understanding of what this technology is actually supposed to deliver – why do we invest in it and what do we want it to do? We are also hearing that AI and Machine Learning technologies will ‘transform’ retailing, bringing significant new opportunities to further satisfy customers and protect retail profits, although what this will look like in practice is still to be determined.

This new report on the use of video technologies the retail industry by Professor Beck is therefore very timely indeed. As with all his work, he focusses a critical lens on the subject, offering a detailed analysis of not only how and why the retail industry utilises a range of video technologies, but also what the prospects, problems and practicalities are of employing video analytics in a retail setting.

We very much hope that this work will help you to develop your own CCTV strategy, enabling you to maximise your investment in this often used and constantly evolving technology.

We would very much like to thank both Professor Beck for undertaking this study and all the retailers and technology providers who so willingly agreed to help him with his research. As always, the ECR Group very much appreciates your commitment to contributing to the development of new thinking and ideas.

John Fonteijn

Chair of the ECR Retail Loss Group

Executive Summary

Background

This research focuses upon providing a detailed and objective assessment of how and why video technologies are currently being used within the retail sector. In addition, it provides a critical review of both the potential and the challenges of utilising video analytics.

It draws upon in-depth interviews with representatives from 22 retailers based in the US and Europe, with collective sales of nearly €1 trillion, equivalent to approximately 12% of their retail market, and operating in over 57,000 retail outlets. In addition, interviews were carried out with representatives from five major video technology providers.

Current Utilisation of Video Technologies in Retailing

For the most part, retailers invest in video technologies to address issues of security and safety although there is a growing realisation that future business cases will need to embrace a more cross functional model, ensuring greater value is realised from the investment.

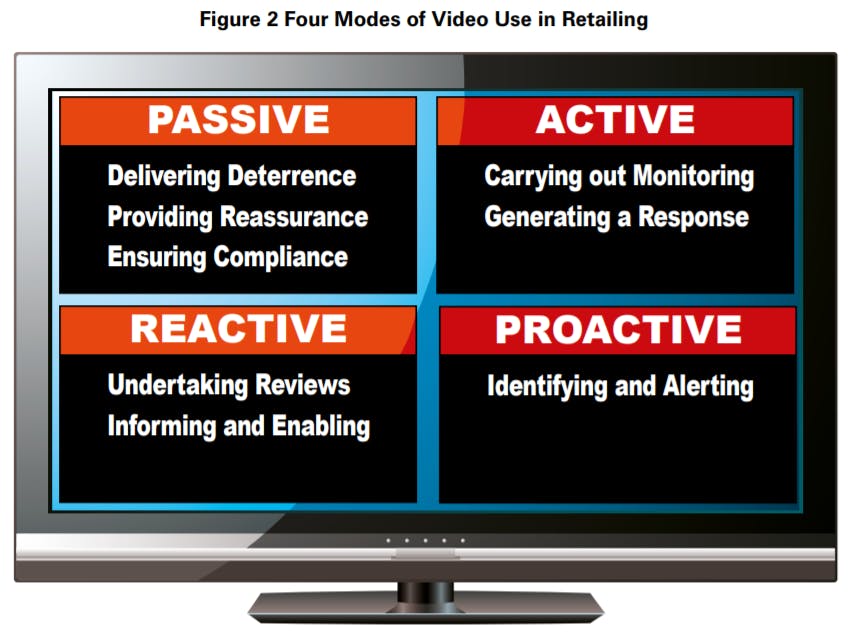

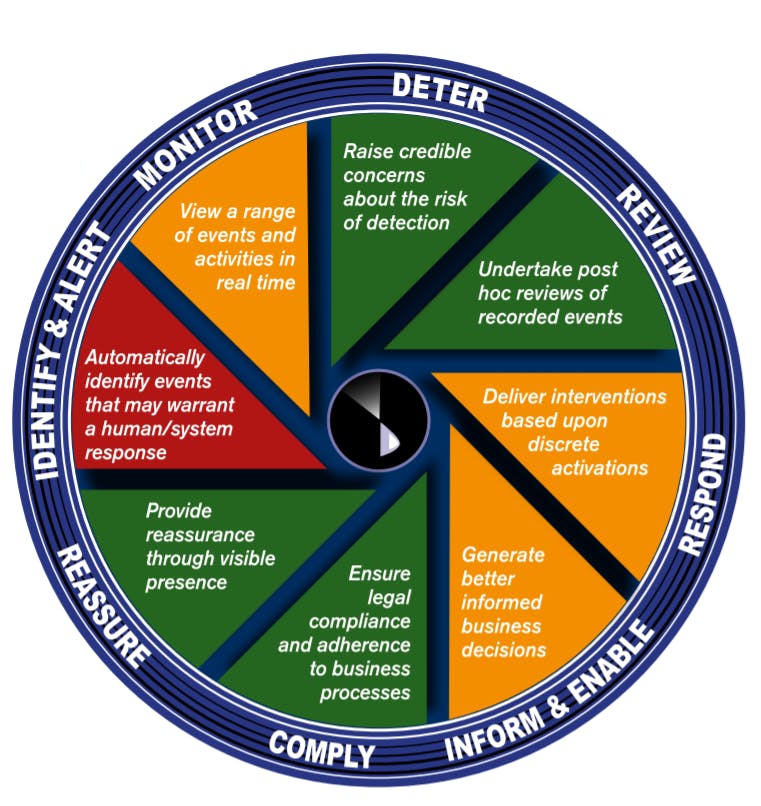

Video Technology Utilisation Model

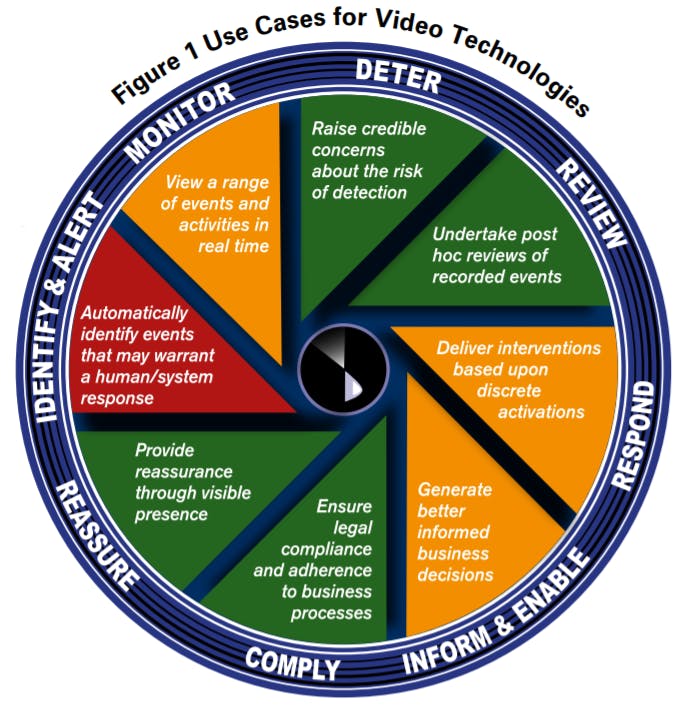

Retail use of video technologies can be grouped into four modes with eight areas of focus:

Passive Utilisation

- Delivering Deterrence: Raising credible concerns about the risk of detection should errant behaviour be considered. There is a growing focus upon ‘personalising’ video-based deterrence, such as using Body Worn Cameras, Face Boxing and Self-scan Personal Displays.

- Providing Reassurance: Generating a sense of safety and reassurance to both staff and customers through its visible presence.

- Ensuring Compliance: Enabling businesses to comply with legal requirements and encouraging employees to follow procedures.

Reactive Utilisation

- Undertaking Reviews: Carrying out post hoc reviews of recorded events for a range of purposes, including: collating evidence to support the prosecution of persistent offenders; scrutinising exception reports generated from PoS and Refund transactions; and reviewing incidents relating to Health and Safety.

- Informing and Enabling: Helping to generate better informed business decisions, such as through understanding customer behaviours and reviewing store designs.

Active Utilisation

- Carrying out Monitoring: Viewing a range of activities in real time, either centrally or at the store level, including random store audits and the monitoring of staff.

- Generating a Response: Delivering interventions based upon discrete activations. Some respondents were offering a centralised service where store staff, activating a panic alarm, received support to help deal with incidents of violence.

Proactive Utilisation

- Identifying, Detecting and Alerting: Automatically identifying events, through video analytics, that may warrant a human/system response, focussed upon security and safety, and business intelligence applications.

Assessing the Use of Video Analytics in Retailing

There is growing interest in the potential of video analytics to contribute to the profitability of retail businesses. However, some respondents had concerns about the extent to which the claims being made about its potential could be translated into reality.

Examples of Video Analytics in Use

Security and Safety Applications

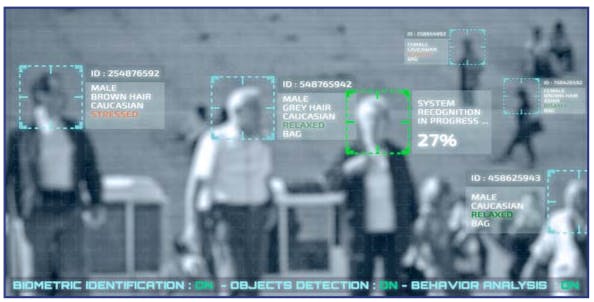

Motion triggers were by far the most common, particularly relating to building perimeters, and areas with limited access authorisation. In addition, some were developing analytics to identify the movement of objects, such as high-risk products. There was also the use of analytics to address losses associated with self-scan checkouts, and some respondents were reviewing the use of facial recognition. Pre-emptively recognising violent incidents is an area of experimental development but thus far, is regarded as fraught with operational difficulties.

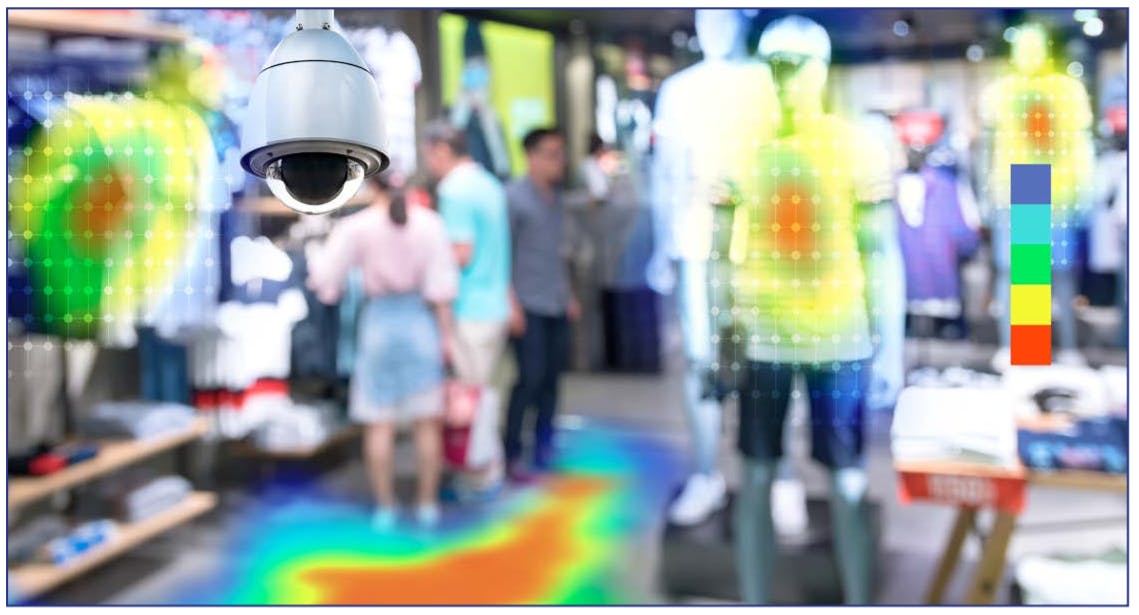

Business Intelligence Applications

Five areas were identified as being the focus of use cases: improving customer service through better staff response times and product availability; generating heat maps and customer dwell times; people counting and queue monitoring; delivery alerts; and improving pick accuracy. Concerns were raised about developing a viable ROI for many of these analytics.

Challenges of Managing Video Analytics

Identifying the Vital Few

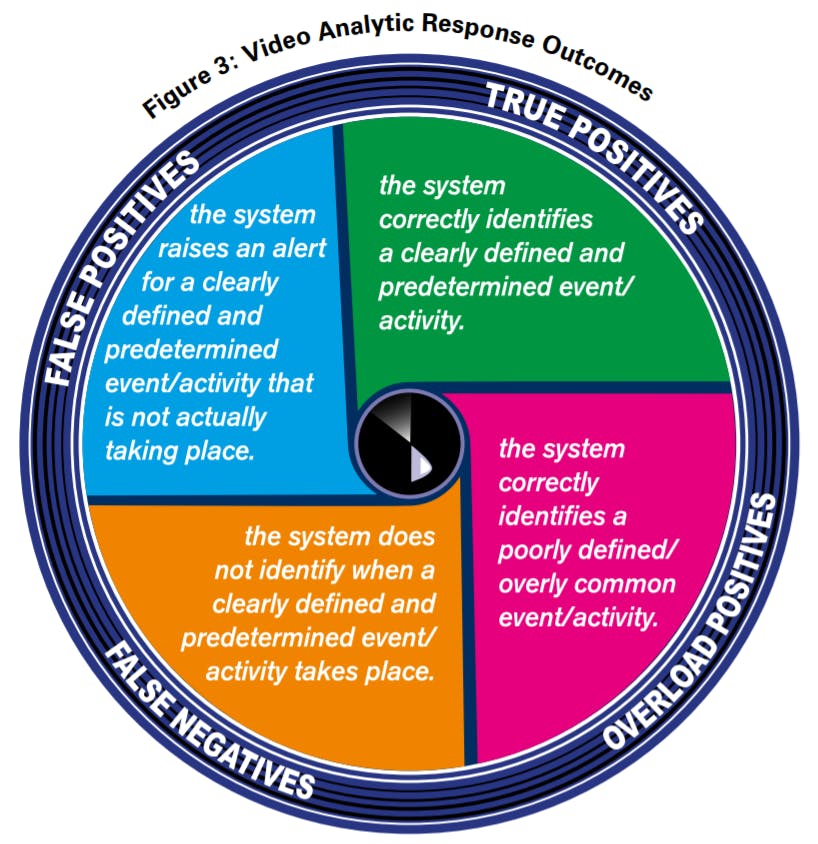

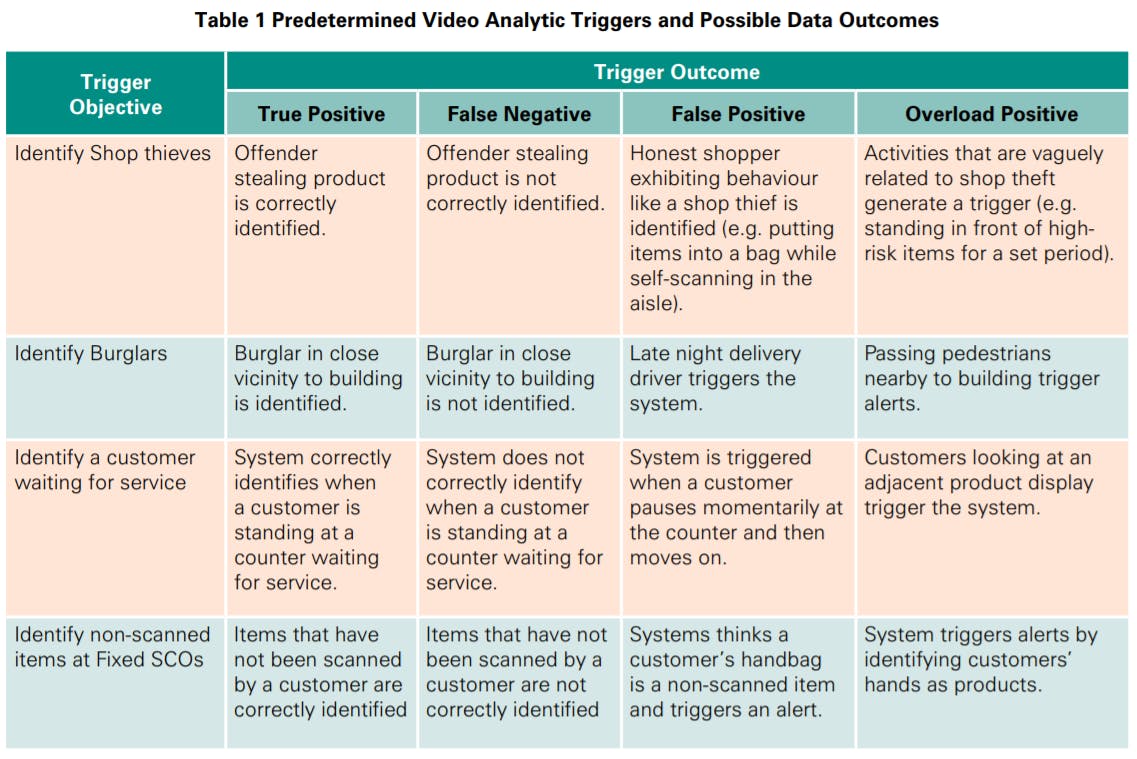

Users of video analytics pointed to the challenges of managing outputs from these systems, in particular the number of False and Overload Positives – the former being where the system has incorrectly identified a predetermined event, and the latter where the system correctly identifies events that are poorly defined and/or are overly common.

The key is developing sufficiently nuanced systems that are capable of accurately and consistently filtering the vital few events from the trivial many. If this does not happen, then there is a danger of them becoming the next deliverer of the ‘Crying Wolf Syndrome’, creating a presumption of error and ultimately alarm fatigue in those tasked with responding.

Managing Scalability Issues

The second major challenge relates to difficulties in applying video analytics at scale, not least because of the significant impact of context on their efficacy. Even subtle differences in the environment within which they operate can drastically affect their capacity to work consistently, requiring detailed contextual tuning. For some this extended process of fine tuning ended up becoming a major distraction to resolving the original underlying problem.

Addressing Bandwidth Issues and Processing

While the cost of computer processing decreases in real terms and many countries are rolling out improved Communications Networks, this research identified concerns about how bandwidth and computing power can impact upon the use of video analytics. This needs to be considered when deciding upon which analytics to employ and the extent to which they are going to be scaled.

Difficulties of Measuring and Proving the ROI

As with many other interventions designed to positively address retail losses and profitability, getting to grips with measuring their impact is a recurring concern. Indeed, this has been a perennial problem for many video-based interventions, particularly where outcomes are often intangible and yet desirable, such as staff safety. But, it is important to develop a co-ordinated and considered approach to measuring how and why video analytics impact upon a retail business, especially when their use cuts across a range of retail operations.

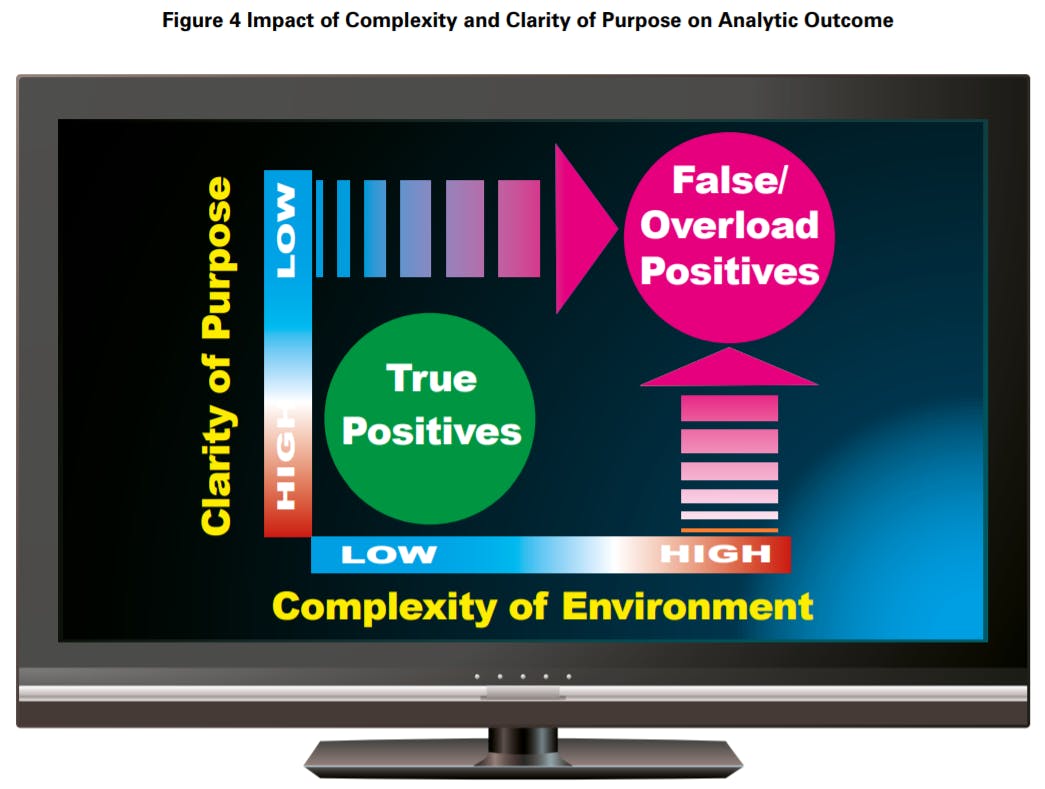

Impact of Clarity of Purpose and Contextual Complexity on Video Analytics

The efficacy of video analytics is undermined by two intertwined factors – clarity of defined objective and degree of operational retail complexity. As the retail environment becomes more complex, both in terms of process and shopper environment, and the link between stated objective and outcome trigger becomes less clear, then the likelihood of False and Overload Positives increases considerably.

Utilising Video in Retailing: A Call to Action

While video technologies have been utilised in some form or other in retailing for over 40 years, the research found few examples of retailers where its role, purpose and capability to contribute to business success was clearly articulated. As detailed already, it is a technology with a broad ranging and rapidly evolving capability, but what seems clear from this research is the need for explicit leadership, greater application across retail functions, improved integration of video technologies with existing systems, and better alignment of video system design with organisational objectives.

Developing Organisational Leadership

As the potential for video technologies to impact upon retail businesses increase, it becomes ever more important that an overarching and cross-organisational approach to developing and managing its use is established. Retail organisations should appoint a ‘video technology tsar’ to positively and proactively lead on the current and future use of these systems. Their role should be to ensure:

- there is a clear and co-ordinated strategy for a pan-organisational utilisation of video technologies;

- the business speaks with ‘one voice’ to avoid duplication of effort and investment;

- that all parts of the business not only understand the potential of what video systems may offer, but also actively facilitate their access to them;

- the establishment clear parameters and methodologies for how the value of investing in video technologies can be measured and understood.

While the Loss Prevention function has traditionally played a dominant role in the use of video systems, it does not necessarily follow that they should take on this leadership role. The move towards greater use of IP-based video systems and the value and importance of system integration, may mean that the IT function increasingly takes on this responsibility. Either way, what is key is that the role of Video Tsar is established, recognised and empowered.

Delivering Cross Functional Use of Video

Making the case for any investment in retailing is increasingly subject to its applicability across an organisation – how might multiple business functions benefit? The application and use of video systems is no different – business cases need to show how they can provide value beyond the traditional confines of the Loss Prevention department.

Building Greater Capacity Through Data Integration

Video systems are increasingly but one of several data sources that can be used to improve operations and business profitability. Technology providers need to work with their retail partners to ensure that, wherever possible, video data is fully integrated into the broader organisational information web to maximise impact and value.

Business Requirements Driving System Design

Unless retailers understand how they want to benefit from investments in video technologies, system designs will continue to be piecemeal, partial and poorly configured. While future-proofing is hard, developing a clear strategy for how it will be used to improve profitability will be a key first step in ensuring that any proposed system design is fit for purpose.

Optimising the Potential of Video Technologies in Retailing

Retailing is a constantly evolving and dynamic industry, hard wired into the economies of most countries. It is also an increasingly competitive and complex environment, demanding businesses to not only be agile and responsive to the needs of their customers, but also make use of a growing array of technologies. While video systems have been used by retailers for some time, primarily to deliver security and safety, it is hoped that this report will provide a stimulus to think more creatively now, and in the future, about how its role can be further developed to enable retailers to meet their core goals of satisfying customers and returning a profit.

Introduction, Objectives and Methodology

Background and Context

It is hard to overestimate the extent to which video technologies are now becoming embedded in societies around the world, although estimates on the scale of the market are often difficult to ascertain, particularly for the retail sector. One technology provider has suggested that the global market for video hardware and software used in retailing in 2020 could be as much as $1.7 billion, rising to perhaps as much as $2.2 billion by 2023 (2) .

This is perhaps not surprising – the use of video technologies is not only longstanding, but also increasingly ubiquitous in this sector – it is hard these days to find a segment of retail space that is not under the gaze of some form of video system (3) . Indeed, retailing has been at the forefront of the use of what are often called Closed Circuit Television (CCTV) systems since the 1970s and 1980s (4) . Primarily deployed as a crime prevention and detection tool, and initially based upon analogue technologies, it is now going through a period of considerable and remarkable change (5) .

This is being driven by a rapidly changing technological and social context, including: major developments in digitisation and associated analytical capabilities; significant reductions in capital costs; advancements in miniaturisation and networking capabilities; and growing societal acceptance of the routine surveillance of public spaces (6) . This has led to the potential role and capability of video technologies in retailing beginning to expand beyond its traditional role as merely a facilitator of safety and security – an insurance safety net should anything untoward happen.

Indeed, what can now be seen is the growing capability of video technologies to be used for a wide range of retail activities, including managing the retail environment, such as controlling access and store functionality, and playing a role in enhancing business profitability, such as enabling customer counting, monitoring queuing, shopper dwell times and stock levels (7) .

However, capability does not always translate into actual use – just because a technology can do something does not always mean that it will be used or operationalised as originally intended, or indeed deliver on initial expectations. For instance, in the early days of the use of CCTV systems in public spaces in the UK, grandiose claims were frequently made about its capacity to significantly reduce crime, which were seldom found to have much veracity (8) .

Similarly, within retail spaces, early studies found little evidence that these systems had much of a lasting impact on levels of retail loss and invariably it was almost impossible to achieve a favourable Return on Investment (ROI) on purely retail loss reductions alone (9) . Equally, it is not clear the extent to which those tasked with using these systems have the capacity and working practices to fully utilise the functionality available – the difference between initial specification and practical application can sometimes be profound (10).

Moreover, the recent rapid growth in the development of video systems that can potentially provide an ‘analytic’ capability – in effect building some form of automation into the viewing, reviewing and responding process, has further heightened interest in utilising these systems more broadly across retail environments, although ensuring that this brings a genuine ‘benefit’ is also the subject of much speculation at the moment.

Talk of video-based Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) technologies being the next ‘big’ transformative change in retailing is currently dominating many trade shows and future gazing deliberations. But whether their introduction and use currently makes sense or are indeed the most appropriate interventions to address the pressing and varied concerns of retailing, is certainly open to debate and critical review.

Purpose of Research

Given this, the ECR Retail Loss Group considered it important to commission research to look carefully at: how current and future video systems can/might contribute to the retail environment; the benefits they can bring; the lessons that can be learnt from those currently using them; and the ways in which this investment can be maximised to have the greatest effect.

As many retailers around the world begin to consider, and in many respects, embrace the transition from analogue to digital video systems, key questions are now arising about how this technology can be utilised to the greatest effect in the retail environment – how can this investment be maximised to benefit retail organisations the most, to create a much more cross-functional and multi-dimensional engagement with the technology?

To date, it has been a technology closely associated with, and focused upon, the delivery of safety and security in retail spaces. However, as this research will show, new use cases are emerging that are beginning to not only significantly enhance its capacity to deliver these objectives, but also enable it to contribute more broadly across retail organisations. This research, therefore, focuses upon providing a detailed and objective review of how video technologies are currently being used, particularly focusing upon the growing area of video analytics and the opportunities and challenges that they present

It should be noted that this research was undertaken prior to the COVID-19 Pandemic that swept around the world in early 2020. At the time of publication, it continues to have a profound impact upon the world of retailing, although how long-lasting its effect will be is impossible to predict. It is also hard to know at this stage how it may influence the use of video technologies by retailers, although early reactions suggest it could play some role in helping to manage customer counting and social distancing (11).

Research Methodology

This study is based upon in-depth interviews with representatives from 22 retailers based in the US and Europe (12). They represent some of the largest retail businesses in the world with collective sales in 2019 of nearly €1 trillion, equivalent to approximately 12% of the total US and European retail market (13). In 2018/19, these companies operated in over 57,000 retail outlets as well as the majority having extensive online operations. In addition, interviews were carried out with representatives from five video technology providers. In total, the research is based upon nearly 30 hours of interviews. Where possible, visits were made to some of the retailers to get first-hand experience of their video systems in operation.

Those retailers that took part in the research were self-selecting – the researcher conducted an online survey, distributed widely through existing contacts, representative trade associations and social media platforms, asking respondents to describe their use of video technologies. Those completing this survey were then asked whether they would be prepared to take part in more detailed research interviews. In addition, through contacts made via the ECR Retail Loss Group and the Retail Industry Leaders Association’s Asset Protection Leaders Council in the US, additional retail companies were approached for interview.

While this study is primarily interested in the views and experiences of retail users of video systems, some technology providers were also approached for their thoughts on aspects of the research. These were selected through existing contacts, size of operation and types of technology being developed. As with the retailers selected for inclusion, this research does not claim to be based upon a detailed and representative sample of the retail industry nor the companies offering video technologies. As such, the results from this research need to be treated with caution – they are only based upon what some companies are using and developing and it is recognised that, given the dynamic nature of this sector, there is likely to be wide range of other video technologies and use cases in existence that are not included.

The companies that agreed to contribute to this research and have their name disclosed are: Abercrombie and Fitch; Adidas; Axis; Big Y; Boots UK; Carrefour; Co-op; Five Below; Genetec; JD Sports; John Lewis & Partners; Lowes; Marks & Spencer; Meijer; Morrisons; Next; Primark; Sainsbury’s; Tesco; Travis Perkins Group; Walmart; and Zebra.

Throughout this report the terms ‘video technologies’, ‘CCTV’, and ‘video systems’ will be used interchangeably to refer to any system designed to observe, collect, collate and analyse both analogue and digital images derived from various types of video cameras. For the sake of brevity, the term ‘Loss Prevention’ will be used to describe the retail function tasked with the management of retail losses.

The topic of video technologies potentially covers an extremely wide range of issues: from technical aspects such as system design and capability right through to why they are used and how. Inevitably, therefore, this study had to focus upon just some of these issues. The report is broken down into three substantive sections. The first is focussed upon developing a more detailed understanding of how retail companies are using video systems. The second section then goes on to look in some detail at the topic of ‘video analytics’, firstly understanding for what purposes they are being used by retailers and secondly, what their experiences of using them have been. The third part of the report then goes on to capture some of the strategic trends in the use of video systems in retailing identified by this research.

Current Utilisation of Video Technologies in Retailing

Introduction

Because retailers have been utilising various forms of video technologies since the mid 1970s – 45 years or more – it may seem odd to begin this research by asking the deceptively simple questions of why do retailers invest in them and for what purposes are they used? However, evidence of ubiquity does not always translate into uniformity of purpose nor understanding of rationale. This section of the report, therefore, focusses upon providing a detailed review of not only why respondents to this research made the decision to invest in video technologies, but also the main ways in which they were currently using them.

The Decision to Invest in Video Technologies

Purpose

Respondents had very mixed views on what the overall purpose of their video systems was although most erred towards what might be regarded as a more established ‘security’ orientation: ‘The main purpose is about the prevention and detection of crime – provide evidence to see what is happening to try and stop it’[RR17]; ‘It [video] protects assets and staff; it’s to deter internal and external theft and identify offenders’[RR9]; ‘Historically it’s been used primarily to catch/identify bad guys…deterring and detecting thieves and investigating crime’[RR13].

"Historically it’s been used primarily to catch/identify bad guys… deterring and detecting thieves and investigating crime."

But for others, the purpose had become much more blurred and unfocussed: ‘What’s the primary objective of CCTV in our business, to be honest, I’m not really sure what it’s for – from a theft perspective it’s pretty limited’[RR6]; ‘We need to figure out our strategy to understand what do we want video to do; if we are not careful we will not have a joined up approach’[RR17]. There was certainly a growing realisation from some respondents that for the investment in video technologies to make sense, then its purpose had to be increasingly more than just delivering a form of securitised comfort blanket:

Business intelligence is where the opportunity is right now; making the argument for spending a lot of money on cameras and surveillance equipment just for the benefit of security is beginning to be a very difficult argument to make [RR3].

As will be seen below, this lack of an overarching common view of the purpose of video technologies in retailing is well reflected in the breadth of use cases to which is it now being used, and while security and crime prevention undoubtedly remain a dominant driver of purpose, other functionality is increasingly being drawn into the broader rationale for using video systems.

Making the Business Case

Since its early introduction into the retail environment, video systems have presented a challenge in terms of advocates showing a clearly identifiable Return on Investment (ROI), particularly relating to the tangible components of retail loss. For instance, installing CCTV has rarely translated into a measurable and sustainable reduction in shrinkage (14). But, in many cases, its role has often been seen as delivering much more intangible benefits that are less easy to capture in a businesses’ P&L, such as staff and customer safety and protecting organisational reputation: ‘Our ROI is much more subjective and intangible but we know that store management are more likely to leave if violent incidents are not resolved’[RR1].

"There is a growing expectation from the police that every store will be connected and so we need to make that happen."

Indeed, video systems are often a form of ‘insurance policy’ – retailers showing due diligence when things go wrong in their spheres of influence and responsibility – was a common response to questions relating to how a business case was developed. This was particularly the case when it came to law enforcement: ‘There is a growing expectation from the police that every store will be connected and so we need to make that happen’[RR5].

As will be discussed below in more detail, there appears to be a broad range of use cases for utilising video technologies in retail, but the challenge has often been collating evidence to either make or confirm a persuasive business case – the data can be hard or practically impossible to gather unless systems have been actively put in place to collect it.

For example, multiple respondents to this research highlighted the positive role they believed their video systems play in managing the issue of false Health and Safety claims made by customers and staff, reducing their insurance premiums by showing due diligence, and meeting requirements set by governmental licencing authorities for the sale of alcohol. All of these clearly make a difference to the profitability of a retail business and yet too often, the ‘value’ of video systems in these types of examples is not actively measured, understood and collated into an overarching business case for their use.

No doubt the ‘intangible’ benefits of ensuring safety and security will prevail at a macro level for justifying the continuing use of some forms of video technologies, but if retail businesses want to expand its use and begin to take advantage of developments in its capability, then they will need to adopt more cross-functional and inclusive business models that more accurately capture the full value they are capable of offering.

Making Use of Video Technologies

Respondents to this research provided a rich tapestry of use cases and applications for video technologies in their businesses and so it was important to try and begin to categorise them into discrete areas of use. As can be seen in Figure 1, respondents’ uses can be broadly grouped into eight areas:

- Delivering Deterrence: Raising credible concerns about the risk of detection should errant behaviour be considered.

- Undertaking Reviews: Carrying out post hoc reviews of recorded events for a range of purposes.

- Carrying out Monitoring: Viewing a range of events and activities in real time.

- Ensuring Compliance: Enabling businesses to comply with legal requirements and encouraging employees to follow procedures.

- Generating a Response: Delivering interventions based upon discrete activations.

- Informing and Enabling: Helping to generate better informed business decisions.

- Providing Reassurance: Generating a sense of safety and reassurance through its visible presence.

- Identifying, Detecting and Alerting: Automatically identifying events that may warrant a human/ system response.

Delivering Deterrence

Since its introduction specifically into retail environments and more broadly in public spaces, a key tenet of video technologies has been their supposed ability to create a deterrent effect – to put off would-be offenders because they are concerned about an elevated risk of being caught. This typically works in two ways: first, creating an increased sense of risk that a security response will be triggered which will lead to a higher chance of being caught in the act; and secondly, an elevated sense of risk that offenders will be identified and subsequently caught and prosecuted (15).

In both scenarios the would-be miscreant needs to not only be aware of the presence of the video system but also believe it delivers a credible risk – either somebody is watching in real time and can respond, and/or the recorded images will be capable of being reviewed and used at a later date for identification and possible punishment (16).

Both in retail spaces and across a wider range of environments within which video systems are now employed, proving this deterrent effect has been difficult – the complexity of measuring deterrence is well known – how can you prove that something didn’t happen that might have happened had the video system not been present? Certainly, studies have been undertaken to try and measure changes in key indicators such as the number and types of crimes and levels of loss before and after the introduction of video systems, but there is often a plethora of confounding factors that undermine the reliability of the results (17).

Of particular concern is the extent to which the growing ubiquity of video systems throughout many societies can and is undermining any form of deterrent impact they might be able to deliver – are the general public and offenders alike simply becoming oblivious to the technological ‘wallpaper’ that adorns many modern urban environments? This is certainly a sentiment that was expressed by many of the respondents to this research.

Fading Impact on Public Perceptions?

A number of respondents were resigned to the view that their video systems no longer deliver a generalised deterrent effect upon would-be offenders: ‘I don’t think people care anymore if there is a cameras system in a store’[RR9]; ‘So we know we don’t see the deter value in having CCTV anymore – that’s gone now’[RR15].

"So we know we don’t see the deter value in having CCTV anymore – that’s gone now. "

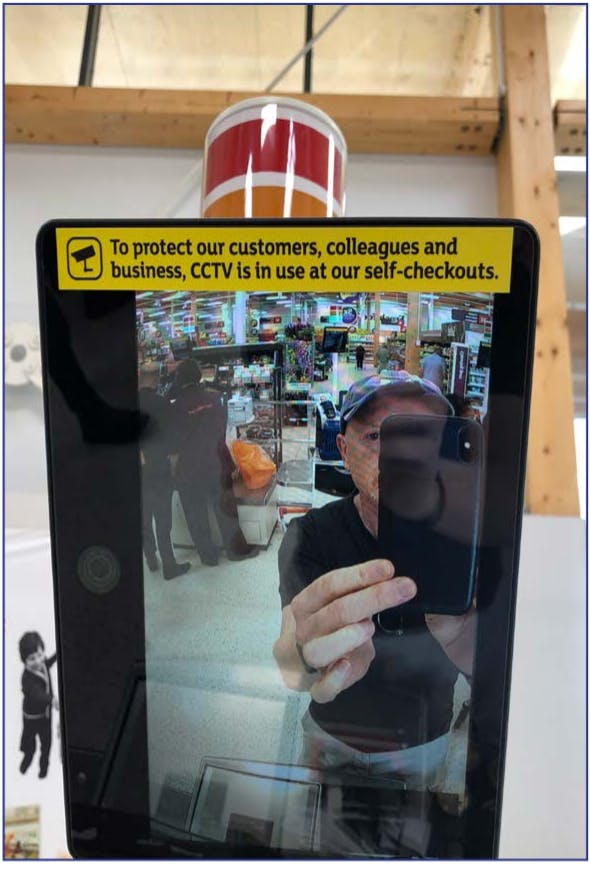

Perhaps one of the most overt ways in which this deterrent potential has been utilised in retail stores is through the use of Public Video Monitors (PVMs), which typically show consumers, via a large display, an image of themselves (and others) entering or visiting particular parts of the store. While some limited research (18) has suggested they do have some impact on rates of loss, one respondent to this research was summarily dismissive of their value: ‘We have stopped fitting PVMs – because they are as effective as a bell box [external burglar alarm box]; everybody has them and nobody needs to be reminded that you have a camera system because everybody’s got one’[RR9].

Delivering Personalised Deterrence

While the generalised deterrent capacity of video systems was regarded by some as waning, there was evidence that the focus of generating video-based deterrence was shifting away from the general towards the specific – making it much more oriented towards the individual miscreant rather than consumers in general. This trend of ‘personalising’ video deterrence was evident in several different technologies being utilised, not least Body Worn Cameras (BWCs), Face Boxing technologies, Selfscan Personal Display Monitors (SCO PDMs) and to some extent patrolling CCTV Vans.

Body Worn Cameras (BWCs)

While the use of BWCs is now relatively common within the law enforcement community in many countries, their use in the retail environment is still a recent development, with several companies in the UK, championing their use. Of the 22 companies taking part in this research, nearly two-thirds (60%) were either using or trialling some form of BWC. The technology, while varying in design and functionality depending upon the supplier and the retailer requirement, was found to be employed for five reasons:

- Generate Deterrence: Show the offender – usually using a body-mounted screen – that their behaviour (including what they say) is being recorded, with a view to this encouraging them to desist from what they are doing.

- Support Prosecution/Punishment: Provide video evidence of miscreant behaviour which can then be used as part of a prosecution/banning order/disciplinary action (19). In addition, some retailers used them to provide video evidence of banning orders being served upon known shop thieves.

- Moderate Staff Responses: Act as a control on staff behaviour when dealing with miscreant behaviour – deter wearers from stepping outside agreed boundaries of acceptable behaviour, such as using inappropriate language, using excessive force or pursuing offenders beyond agreed zones of engagement. This in turn can reduce the likelihood that the business may be subject to legal redress later.

- Offer Reassurance: Provide reassurance to wearers and other staff in their proximity through increasing their perception that there is an increased likelihood miscreants will be identified and prosecuted/banned.

- Inform Staff Training: Enable video images to be captured, which can then be used for training purposes, to improve the way in which retail employees recognise, avoid and respond to challenging customers and incidents.

Of the 13 companies using or had tried using BWCs, the majority employed them only on in-store security guards (70%) while just two retailers had taken the decision to offer them to retail staff, although a third company was contemplating doing this. A further four companies were using them for different types of staff and settings: one was employing them on employees responsible for home delivery, another had provided them to security guards operating in distribution centres and at the Company’s Headquarters; a third had given them to security staff patrolling vacant properties; and a fourth utilised them on security staff issuing banning notices to known shop thieves.

Several respondents expressed their reluctance to deploy BWCs on retail staff, concerned about the type of image it might portray:

… there is that ‘military’ effect on how staff look – do we want our staff to look like the military? There is a nervousness about whether we want this in all our stores. Is it brutalising the retail space? For some it reassures, for others it’s a barrier [RR18].

Others were also concerned about the way in which they may be perceived when used by retail staff: ‘There are concerns from some pockets of the business about its impact on customer perceptions of the retail space – is it not safe?’ [RR16].

Whilst it was not possible to get extensive and definitive data on the extent to which the use of BWCs had impacted upon levels of violent incidents in retail stores, seven of the 13 companies had carried out some form of evaluation/review, often based upon small trials in a few stores looking at their impact on the number of recorded incidents. In addition, some had surveyed the wearers of BWCs to ascertain their views on using the technology.

For all those that had carried out a trial, they found that the use of BWCs was associated with a reduction in the number of incidents of violence and verbal abuse: the lowest reduction was recorded at 30% while the highest was an 80% reduction in these types of incidents. Overall, when averaging across this data, the use of BWCs was associated with a reduction in the number of violent and verbal abuse incidents by about 45%.

For the most part, staff attitudes to the use of this technology was very positive: ‘It’s been a very positive story for us; feedback is really good’[RR2]; ‘Staff absolutely love them’[RR6]. None had found any negative feedback from customers and indeed some argued that they viewed them as an indication of the extent to which the business was taking safety and security seriously.

A small minority of respondents did identify some issues from users – one suggested that their feedback had been more mixed with some staff concerned about being filmed and having their actions scrutinised. Another staff survey found that while one-third of users had felt safer wearing the BWCs, the same proportion did not feel any safer. For one company their trial use was brought to an end because of concerns about how they were being used in retail stores: ‘the problem was with compliance – being used when they shouldn’t have been; until we can get this right, nobody is going to be using them in retail’[RR15]. Notwithstanding these views, most of the feedback from the 13 companies employing this technology was very positive indeed.

"It’s been a very positive story for us; feedback is really good."

In terms of next steps, respondents suggested several ways that they might move forward with this technology:

- Roll out the use of BWCs to more stores and staff.

- Look at ways to connect the BWC unit to a Security Operations Centre (SOC) via a panic button.

- Consider less overt, more discrete forms of the technology for retail staff.

- Encourage users to trigger recording before an incident escalates, such as capturing images as they approach a situation and the surrounding scene.

- Track the location of BWCs to ensure users are not going beyond agreed zones of engagement.

- Possible use on home delivery staff although there were concerns around privacy and data protection issues (20).

- Monitor staff usage to avoid deployment slippage.

- Consider live viewing via a SOC although concerns about the number of false positives was deterring many from trying this idea.

Face Boxing

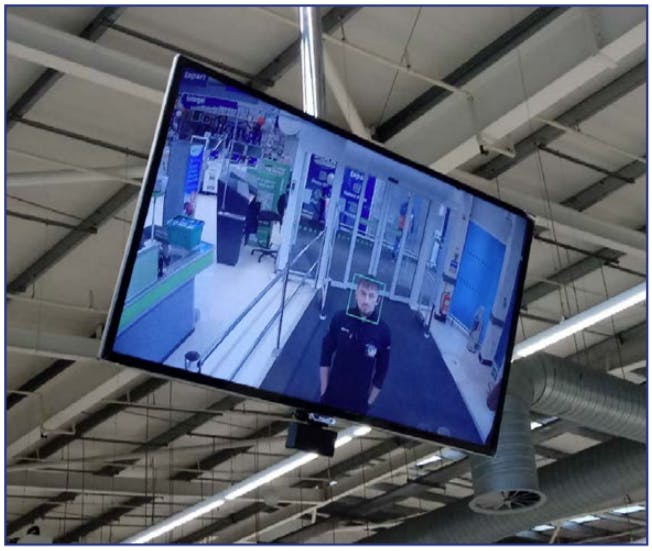

While certainly less prevalent than BWCs, the use of ‘Face Boxing’ on Public View Monitors (PVMs) is another example of how retailers are beginning to try and ‘personalise’ the deterrent component of their video systems. This is a relatively simple technology that digitally ‘draws a box’ (some companies used a green box, while others a red box) around the head/ face of all those entering a retail store.

The general idea is that it gives the impression that the company may be using some form of facial recognition (even though this technology was not actually in use) or it simply catches the attention of the consumer: ‘We use Face Boxing on PVMs – nothing being stored; it is a relatively crude technology to give the impression we have FR [Facial Recognition] in operation’[RR20]. For another it was felt that this technology better drew the consumer’s attention to the presence of video systems in the store:

We have put in 40” monitors in stores that puts a green box around customer faces as they walk in – you can’t but notice that you are on the monitor – hung very low down at the entrances. We are trying to make it more obvious that the customer is on CCTV [RR2].

As with many other video systems, it is very difficult to know the extent to which this type of technology has an impact on levels of loss or incidents of violence and verbal abuse, although one respondent claimed that it had had an effect: ‘in the stores where it has been used we have seen a drop in losses and a drop in incidents of violence’[RR5].

Self-checkout Personal Display Monitors

A third technology which highlighted this drive towards generating a more personalised video-based deterrent was the increasingly widespread use of video screens attached to Fixed Self-checkout (SCO) terminals showing an image of the person using it and, in some cases, the products being scanned. As other ECR research has shown, the risk of errant behaviour at SCO terminals is a growing concern, particularly from users either not scanning items at all or mispresenting items to secure a lower price (21).

Because of the relatively un-supervised nature of this type of checkout and the elevated risks associated with it, retailers have been introducing a range of approaches (such as video-based technologies, revised store processes, changes to store design, and improvements in staffing levels and training) to try and address their losses.

Emerging research suggests that much of this loss may well be due to a group of shoppers who would not normally engage in overt shop theft behaviour now taking advantage of the perceived low-risk opportunities these systems offer – previously ‘honest’ shoppers now engaging in relatively small-scale, hard to prove theft.

While this is a disturbing outcome from the introduction of SCO technologies, it is also the case that this new group of miscreant opportunistic shoppers is also highly likely to be very risk averse – they are relatively easily deterred or ‘nudged’ back to honesty. For the most part, they would rarely view themselves as shop thieves or have entered the retail store with an explicit agenda to steal at scale.

Therefore, any ‘amplification’ of the risk of getting caught is likely to drive them back to honesty. In this respect, the use of SCO PDMs is an example of retailers further personalising the risk amplification process: ‘look, we are recording what YOU are doing at this SCO machine’. Respondents to this research echoed this: ‘SCO is a big risk for us, we need to show the shopper that they will get caught and we think PDMs help to do this’[RR20].

It is still early days in terms of understanding the effectiveness of any of the various ways in which retailers are trying to moderate SCO-related losses, but one major UK Grocer has shared some of their findings relating to the use of SCO PDMs. In a trial based upon measuring the change in store shrinkage in 10 stores before and after the introduction of SCO PDMs, they found that losses were significantly lower in nine of these stores (22). While encouraging, more research is required to understand the extent to which these systems impact upon store losses and whether their ‘potency’ is eroded over time as has been found with other forms of video-based deterrent (23).

CCTV Vans

While not as strictly ‘personalised’ as the examples above, one of the respondents to this research shared their experience of trying to generate a more credible and focussed deterrence to counter criminality around their stores. This was done using highly overt vehicles equipped with video and audio technologies that could be targeted on high risk areas/stores:

They patrol in car parks and have a guard inside; they are a good deterrent; the guard will respond if something is happening. It looks like a police van, has a mast that goes up and also has a PA system [RR14].

Other companies had also explored the use of overt semi-mobile video systems deployed in car parks focussed on both deterring crime and, in some instances, helping to collect evidence. As with the other interventions described above, it was not possible to collect any verifiable data on their impact over time beyond anecdotal evidence provided through these research interviews.

Deterrence and Impact of Video Systems on Staff Theft

The final area relating to deterrence that was discussed by respondents was the impact the introduction of video systems can have upon levels of internal theft and process-related losses. Very often the focus of attention is upon the threat from external actors, namely shop thieves, but numerous research studies have highlighted the threat that can come from within, from the people retailers’ employ in their businesses (24).

Video systems can be installed to try and manage this issue in various ways, such as locating cameras above Points of Sale (PoS) to deter staff from stealing cash and/or giving stock away to family and friends (sweethearting), positioning cameras in backroom areas to deter the pilfering/ eating of stock, and within secure spaces, such as cash offices, to again deter the theft of cash. For one respondent to this research, the introduction of video systems into their stores was primarily focussed upon driving down internal losses:

I believe that the reason this is happening [lower losses] is because of the reduction in the risk of internal theft. People act differently when they believe they are being monitored. Also has helped to improve store execution – stores begin to tidy up the backrooms, hallways, store floor areas. Appears to have significant deterrent value for staff in particular [RR7].

This company had measured the impact of this investment and argued that every store installation thus far had received a positive ROI within one year based upon a reduction in recorded store shrinkage: ‘When we invest in CCTV, the shrink reduction pays for the cost of the installation in the first year’[RR7]. Further data from this company showed how the shrink savings continued for a further 2 years after installation before levelling out – this was compared against a sample of control stores where they had yet to install CCTV.

These are certainly impressive findings indicating a good result in stores where a video system is installed where nothing was previously present. For most retailers, however, few will be in a position where they have not already introduced some form of CCTV into their stores and therefore, they are unlikely to be able to observe similar levels of success.

"When we invest in CCTV, the shrink reduction pays for the cost of the installation in the first year."

Undertaking Reviews

While deterrence was a widely articulated passive use case for video systems in retailing, using them more actively to undertake reviews of recorded images was almost as prevalent in the companies taking part in this research. Globally, retailers are probably one of the largest non-governmental routine collectors of video images: ‘A several hundred store chain with 10 lanes of checkout will probably have 1,000 years of video stored at any point in time!’ [RR15]. This enormous library of images represents both a challenge and an opportunity to retailers – a challenge in terms of how to retain and access this information, and an opportunity to review activities that may be of value to the business.

It is important to recognise that this form of video review is not generally regarded as video analytics – the selection of images to review is rarely automated or driven by algorithms but done simply by other data triggers or manual interventions. At the moment, most of this reviewing activity is focussed upon events that are, or may, pose a risk to a retail organisation, and is therefore typically undertaken by loss prevention-focussed staff.

Most respondents to this research identified three main areas where post hoc review of video images was taking place on a regular basis: collecting evidence on persistent offenders; scrutinising exception reports from PoS systems; and reviewing incidents relating to health and safety. In addition, several respondents also described some of the other ways in which they were using their video systems to review events and activities, but these were much less common and are therefore described together at the end of this section.

Collating Evidence to Support Prosecutions and Alerting Store Teams

For numerous retailers their post incident video reviewing process was focussed upon trying to collate sufficient evidence on persistent offenders to facilitate either their prosecution by the criminal justice system or the imposition of company-specific banning orders: ‘We build dossiers on repeat offenders and then give them to the police’[RR5]. Others echoed this use and the value video images brought to this work: ‘We create a folder with all the available evidence including CCTV and then give this to the police – without video they won’t do anything’[RR10].

“ We build dossiers on repeat offenders and then give them to the police."

For those retailers that had developed a centralised security hub, this was one of their core activities although for businesses with many physical stores, delivering this at scale was at best challenging. In addition to building evidence files on persistent offenders, some respondents used the review of shop theft incidents to alert store staff of potential criminal gangs that may be heading in their direction: ‘We send reports out to stores warning them of potential gangs in the area – what they look like and what they might target’[RR10].

Only a very small minority of the respondents to this research who were undertaking this type of activity were able to put a monetary value on the ROI – not least because it is very hard to maintain an accurate flow of data once a persistent offender case file is shared with the police or store staff are given advanced warning of a criminal gang operating in their area. Given all the myriad other factors that impact upon shrinkage in a retail store, it is almost impossible to show any causation between changes in levels of loss and the post hoc review and collation of images of persistent shop thieves. That is not to say that this type of work has no value, but more a reflection on the challenges of justifying the business case for investing in video for this purpose.

Scrutinising Exception Reports on PoS and Refund Transactions

A second area of video review related to assisting in the assessment of retail transactions deemed to be ‘unusual’ or exceptional. This is an example of where video played a confirmatory role when connected with other systems, such as data mining software utilised to analyse PoS and Refund data: ‘The [PoS] data is always the instigator and the video the verifier’[RR17].

“ The [PoS] data is always the instigator and the video the verifier. ”

Numerous systems exist that ‘mine’ PoS data for unusual or exceptional activity, such as staff members who perform well above the average number of refunds or voids or carry them out at unusual times such as when the store is officially closed to customers. It is then the task of loss prevention investigators to determine the veracity (or not) of these ‘exceptional’ transactions and, where appropriate, build a case to act against a member of staff deemed to be behaving inappropriately. Without the capability to review video images of these transactions and events, it would inevitably be a time-consuming and challenging process.

Respondents using their video systems for this purpose highlighted the value and importance of having them synchronised with their PoS systems/Data Analytic software: ‘We have the CCTV system connected to PoS – we can review video at the same time as the transaction – the key is having time synchronisation between cameras and PoS system otherwise searching can be time consuming’[RR7]. Another illustrated the value of doing this:

We use an exception reporting system called [name of provider], connected to CCTV and they are synchronised in terms of time – this probably saves 15 minutes per event, 50 events per week adds up to a considerable amount of time – allows us to review a lot more exceptions and so increases the chance of finding incidents [RR1].

While some had begun to look at ways in which the video data could offer more of an analytic capability, especially when trying to identify fraudulent behaviour amongst the very large volume of customer refunds most retailers have to deal with, none felt they had adequately addressed the high volume of false positives that are generated at the moment, something which will be discussed in more detail later in this report.

Assessing Health and Safety Incidents

Where the post hoc review of video images was deemed to be of particular value was in relation to ‘accidents’ occurring in retail premises, such as customers and employees tripping and falling: ‘If somebody has an accident, there will be a review and then if the injured person files a claim then the video would be reviewed’[RR17]. Depending upon the part of the world in which a business operates, this is probably one of the most expensive areas of liability a retailer faces on a regular basis. In the UK for example, over 11,000 retailer employees a year are involved in slips and trips resulting in a serious incident and it has been estimated that health and safety related incidents were costing in the region of £5.2 billion a year (25).

While most health and safety incidents are probably genuine, respondents to this research highlighted the value video data can play in checking the veracity of any given claim: ‘In a depot there have been 4 or 5 claims which have been proven to be false – historically we would have just paid out to protect the brand but now there has been a cultural change as a consequence of putting in the cameras’[RR17].

This was echoed by other respondents who pointed towards a pre-video corporate culture of presumption of liability and payment of claims due to a lack of easily accessible counter evidence. Several respondents were able to offer, albeit rather anecdotally, evidence of the positive impact of now using video systems to review the degree to which their businesses were genuinely liable for health and safety-related incidents.

“ After the first year we had the same number of claims but we paid out 15 times more on the claims prior to putting those cameras in – they literally paid for themselves within the 2nd quarter. ”

For example: ‘After the first year [of installing the video system] we had the same number of claims but we paid out 15 times more on the claims prior to putting those cameras in – they [the cameras] literally paid for themselves within the 2nd quarter’[RR4]; ‘I reckon we have saved over half a million in false claims in the DC – such as showing staff messing about on forklift trucks before they got injured’[RR5].

For another respondent who was in the process of updating their video system, part of the rationale was based upon reducing the corporate liability bill:

The Risk Department is exceptionally excited by the prospect [of having access to the video system] and Customer Service are now looking at the video to see whether the company should pay out, and how much – I think half of the claims we currently get are false [RR18].

Two respondents also highlighted a related financial benefit of having a video system capable of effectively monitoring and limiting a businesses’ exposure to false claims, namely a reduction in the cost of insurance premiums: ‘At the moment we pay out on nearly 90% of claims against us due to no CCTV … we believe we can reduce our insurance premium by 50% by showing them the processes we [now] have in place’[RR18]. Another respondent was prepared to put a value on now having an IP networked video system and its impact on reducing their insurance premiums:

… I would probably say between 2-5%. Our premiums are experience rated, meaning that the insurer looks at our claims experience and provides premium rates from that. CCTV has probably reduced the value of many claims and entirely defended others, therefore I would be confident that our claims experience is much better for having the CCTV [RR23].

“ At the moment we pay out on nearly 90% of claims against us due to no CCTV … we believe we can reduce our insurance premium by 50%.”

Other respondents also pointed to the way in which having incidents recorded reduced their liabilities through having the capacity to show due diligence when a case went to court: ‘We have seen certain types of claim – mainly acts of violence – reduced because we can now show due diligence on the part of the company in their efforts to try and prevent the incident from occurring’[RR11]

Finally, two companies described how they used their video systems to proactively manage their exposure to the risks of health and safety claims. The first tasked SOC staff in quiet periods to carry out random spot checks on stores looking for breaches, such as blocked fire escapes. The second used their networked video system to prioritise training and maximise the use of limited resources:

Our safety manager will, rather than travel to 80 stores and spend all his time behind a steering wheel, he will do a video audit to identify which stores he should go to and do training – the video helps to decide where to go to first [RR4].

As with the other areas where video was being used to review incidents and events, there was a general lack of attention to try and accurately measure the financial value it was bringing to the business. However, in many respects, this is more a case of a lack of prioritisation than a challenge of data collection – the methodology to understand the value video systems can bring to the management of health and safety-related incidents is relatively straightforward to envisage (26).

As will be discussed later in this report, if retailers wish to reap the benefits from the use of their video system in this area, then they will need to design it accordingly – as one respondent put it: ‘Prior to its installation it was always the case that a slip and fall happened where we didn’t have a camera’[RR4].

Other Review Activities

In addition to the three main areas described above, several respondents also described some of the other ways in which they were reviewing their recorded images although these were far less common.

Conducting Store Audits

Some respondents shared how they used their video systems to remotely undertake routine store audits based upon recorded data. This was done primarily to give constructive feedback to a sample of stores, such as those that had recently opened or were experiencing unusual levels of loss. One respondent described their process:

We do CCTV observations or snapshots – take a period of time when a member of the team will take one hour to look at previously recorded information – such as review engagement with customers at PoS, then share the results with the rest of the organisation [RR7].

Another described how they utilised this type of audit process to: ‘… create an illusion of centralised watching and checking’[RR19], in effect try to generate a Foucauldian-style response in store managers (they are not sure whether they are being watched or not and so temper their behaviour accordingly) (27). This is an interesting idea but again, almost impossible to measure its impact.

Assessing In-store Violent Incidents

One respondent described how they used their recordings of in-store violent incidents to review how staff had responded to them, with a view to improving their employee training. In this respect, it was an interesting example of video review enabling the business to understand mistakes being made by their staff: ‘we found that in 24% of incidents staff were “overly” involved, in other words not doing what we had told them to do’[RR5]. No doubt including these images in future training sessions would be a very useful way of embedding better staff practices around the management of these types of incidents.

Checking Delivery Discrepancies

An innovative use case offered by another respondent related to using the review of recorded images to investigate discrepancies in deliveries from third-party suppliers. In this example, a retailer received direct-to-store deliveries from suppliers and where a store manager subsequently queried the accuracy of any given delivery, video footage was reviewed by the SOC (28). It was recognised that this was only really possible where camera coverage was good enough and the discrepancy was of sufficient size to make its identification possible, such as missing pallets or roll cages, but it was viewed as another use of the review capability of both the video system and the SOC.

Reviewing Customer Claims

Finally, one respondent described how they used video review to ascertain the veracity or not of a certain type of customer claim via their online business. In this example, the retailer had positioned cameras over the area where customer orders were collated and packaged ready for despatch. When a customer made a claim that their delivered order was missing several items, these images could be reviewed to understand whether the claimed missing items had been included when the order was originally packed.

As with most video review activities, the retailer was not able to put a value on this capability, but they did suggest it was in use ‘extensively’. As with some of the other examples described above, it would not be difficult to begin to develop ways to measure this value, which could then be used to help build a more cogent and persuasive business case for the use of video in retailing. It would seem the challenge lies in businesses developing a more co-ordinated and cross organisational management of the utilisation of their video systems, something which will be discussed later in this report.

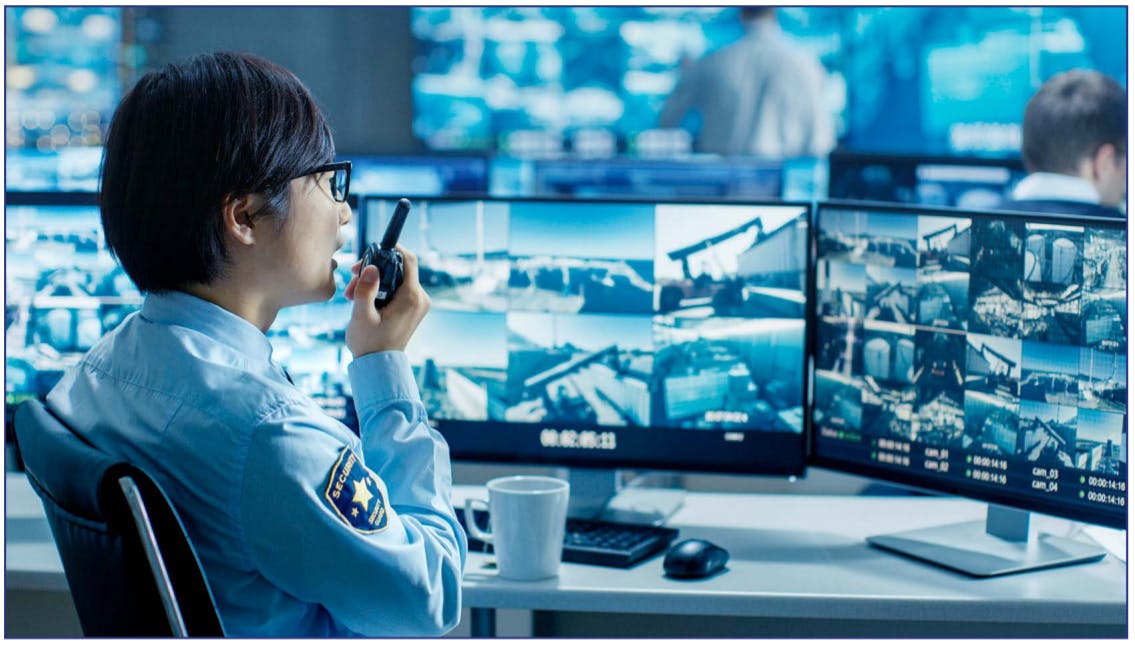

Carrying out Monitoring

The third way in which some respondents were utilising their video systems was to use them to enable real-time viewing. When CCTV was first introduced in a range of settings, this was considered to be the primary way in which it would be used – operators ‘watching’ over surveilled areas ready to react to any given incident or event (29). This is best characterised by the ‘wall of monitors’ often seen in some SOCs and other CCTV control centres (30).

However, the reality in most cases is that using humans to try and identify miscreant behaviours via video feeds from what can sometimes be tens of thousands of cameras often covering large, complex, crowded and rapidly changing environments, is at best ‘challenging’ (31). Many thefts in retail stores can be quick, discrete and covert events that are hard to identify at the best of times. When they happen in large crowded stores, the odds of most video operators watching the ‘right’ screen

at the ‘right’ time to witness the event is vanishingly small (32). This realisation has led many retailers to significantly curtail the extent to which they have staff actively monitoring real time video feeds – achieving a ROI is extremely difficult if not impossible in most cases.

However, several respondents to this research did identify some of the limited ways in which real time monitoring did take place within their organisations.

Centralised Monitoring

One company made use of a HQ-based security function to undertake real time monitoring of selected stores at night:

The HQ gatehouse will monitor in real time selected stores – every night they get a list of stores to review. If they see anything they will report it and every morning they then complete a report which is shared with the [reviewed] store and the LP team. Stores are chosen mainly on risk but also physical changes, a tip off, new stores etc [RR14].

Similarly, another company utilised video review at night to monitor the activities of replenishment staff: ‘We know the staff working night crew are aware that Big Brother is watching – the phone is ringing seconds later saying “hey why did you in the red coat walk out the door just now, you didn’t call me”’[RR4]. In both these cases, the much less dynamic and complex nature of the night-time store environment probably made the identification of ‘exceptional’ activities much more likely to be witnessed by those watching.

Another company provided real time monitoring when a store reported a particular type of incident, which would then be managed centrally with the SOC communicating with local loss prevention teams to deploy resources where necessary and collect evidence. Interestingly, one company described how their SOC used real time monitoring to provide reassurance to staff feeling concerned about their safety: ‘[Store] Staff can phone the SOC if they feel vulnerable entering and leaving a store so that they can keep an eye on them’[RR2].

“[Store] Staff can phone the SOC if they feel vulnerable entering and leaving a store so that they can keep an eye on them. ”

Finally, another respondent described how they used real time centralised monitoring to undertake ‘virtual’ store audits in some of their stores to check on process compliance. It was stressed that this was done in a ‘positive’ way – providing constructive advice and feedback – rather than as a draconian ‘big brother’ intervention, because of concerns about staff morale and accusations of HQ ‘spying’ on stores.

In-store Monitoring

In the not too distant past real time in-store monitoring was probably one of the biggest uses of video systems – a security guard either in a darkened room watching multiple screens, or at a CCTV podium situated near the entrance of the store. While the latter remains a relatively common sight in larger retail stores, the reality for some respondents was that this was as much about creating a deterrent effect as it was about actually enabling guards to identify miscreant behaviour in real time – part of the development of an illusionary ‘theatre of security’ to amplify a sense of risk (33).

In an effort to make video feeds more accessible as the role of the guard changes, one company was trying out new ways to do this: ‘We are going to try out “mobile podiums” – the guard will carry around a mobile device that will give them access to the CCTV store system’[RR14].

No doubt in certain locations and types of retail environment there may well continue to be a case for real time monitoring of multiple video feeds, but the reality of ever growing staffing costs, increasingly complex retail environments, and the rapidly developing capabilities of video analytics, may well mean that this use case becomes less evident in the retail environment of the future.

Ensuring Compliance

As the application of video systems in a wide range of environments expands around the world, some retailers have increasingly found that their use is no longer a business choice but rather a statutory requirement for them to be able to either operate in particular locations or trade certain types of goods (34). In addition, and as detailed earlier, some retailers have also pointed towards the way in which the use of video systems can encourage greater compliance on the part of employees. The issue of Compliance, therefore, is the fourth use case for video systems.

Meeting Legal Requirements

Like many advancements in technologies, the early use of video systems largely developed within a regulatory vacuum; users had little guidance or control over how and where they should or should not be used. Since then, many countries have developed laws and regulations covering the use of video systems in public and indeed private spaces, with some setting very strict limitations on who and what can be surveilled and for how long images can be retained (35).

However, in some countries, there are also statutory requirements for the use of video systems by retailers when operating in what are regarded as high crime/risk areas and when selling certain agerestricted products such as alcohol and cigarettes. While some respondents were not fully clear exactly why some local authorities tied the issuance of alcohol licences to the installation of CCTV: ‘we don’t know why they want us to have it…’[RR17, it was evident that this consideration was part of the rationale for its introduction. As with other use cases, it was not possible to identify the monetary value that this brought to any given retailer, although it can be imagined that for some grocers in particular, not having the opportunity to sell alcohol would create a major dent in sales and profits.

Influencing Staff Behaviour

One other issue relating to the way in which video systems were used to ensure compliance related to their impact upon staff behaviour. As was discussed earlier, one retailer who was introducing video into their stores felt that it had a positive effect upon staff compliance to company processes. For another respondent they thought it impacted not only in this respect (process compliance) but also in terms of the way in which video mitigated staff responses to incidents of customer theft: ‘… staff won’t go out on a limb and ignore company policy, such as tackling a shoplifter outside the store if they are going to be caught on cameras as well’[RR17].

“ … staff won’t go out on a limb and ignore company policy, such as tackling a shoplifter outside the store if they are going to be caught on cameras as well. ”

This is a similar moderator effect as described by some respondents to the use of Body Worn Cameras where the recorded evidence could be damning for both the offender and the wearer of the device. Of course, this type of effect (staff compliance) overlaps with the issue of deterrence as discussed earlier and requires staff to be not only aware of the presence of video systems but also believe they are effective and will invoke a reaction.

Generating a Response

Four of the participating companies had developed a particular use case for their video systems that utilised them to create a centralised response to incidents of violence against store staff.

Store Panic Alarms (36)

In all cases, some form of panic alarm device had been installed in retail stores which when triggered, would raise an alert at a Security Operations Centre (SOC). Staff in these centres would then begin viewing the live video feed from the store activating the alarm and take some type of action to try and encourage the offender to desist. This could take the form of a recorded audio message or a real time announcement addressing the offender directly. One respondent graphically described how they thought this worked:

Some call it the ‘voice of God’ effect – shocks offenders into changing their behaviour; it is also a real voice and not a recording – can make the message context specific: ‘you in the red jacket…’ [RR5].

Another respondent stressed the importance of having the capability to talk directly to the offender: ‘operators have the licence to decide what they broadcast given what they can see and what they think might put them off’[RR19]. They also stressed the importance of ensuring that those who do respond are given good training and support to deal with what could be stressful situations.

“they are more likely to respond if you have a visual verification of what is happening. ”

Another retailer using this type of system also highlighted the way in which it fostered a better relationship and response from the police: ‘they are more likely to respond if you have a visual verification of what is happening’[RR17].

Retailers offering this ‘service’ to their stores could only provide limited evidence on the extent to which it was impacting on levels of store violence although all thought it had been very effective in not only reducing the number of incidents but also acting as a form of reassurance to store staff: ‘they feel better that somebody is there; we get staff to point out the cameras to offenders’[RR19].

Undoubtedly, this is not a ‘cheap’ utilisation of a video system – it requires a centralised, adequately staffed and networked facility to enable it to work. But, as will be discussed below, if a retail business has taken the decision to invest in a SOC for other primary reasons, this could be a further application to bolster the business case, especially for those retailers that have stores in high risk areas and/or sell products that make them more prone to violent incidents occurring, such as pharmacy, alcohol and cigarettes.

Providing Reassurance

As discussed earlier, one of the challenges of measuring the ‘value’ of video systems is that it can be tasked with delivering outcomes that are often hard or impossible to quantify financially – the intangible benefits that are much discussed and appreciated, but rarely capable of being included on a business’ P&L. A good example of this is the sixth use case identified by respondents, which is Providing Reassurance.

Staff and Public Safety

As one industry sage has often put it: ‘a video camera won’t leap off the wall and stop a member of staff being attacked’, which is true, and yet frequent security surveys have shown that staff and members of the public are often reassured simply by the presence of CCTV (37). So how does this work? It could be that the video system provides a visual reminder of four things: security is being taken seriously by the business; somebody is looking out for me; somebody can send help if anything were to happen; and if something does happen, whoever did it is more likely to get caught and won’t be able to do it again. One of the respondents summarised how they viewed this:

From a colleague perspective, I feel reassured that if anything happens then there will be evidence available. Staff feel reassured because they think the cameras will generate a response. The reassurance comes from the fact that evidence will be available after the fact and that will increase the likelihood of the offender being arrested and prosecuted. As long as staff perceive it like that, then that’s good [RR17].

Of course, the reality for most staff who are operating in retail stores not offering the panic button-based system described above, is that their store video system is essentially just a symbol of organisational commitment and potentially a means to collect post-hoc evidence should violent incidents occur (38).

For customers, the presence of video systems in retail stores is now very much a given, perceived as an integral part of the fabric of modern retail environments and one part of a societal infrastructure of security technologies increasingly visible across many urban spaces.