Developing a Framework for Understanding and Measuring E-commerce Losses in Retailing

Table of Contents:

Languages :

Shopping online is now a big and ever-growing part of our retail world, and certainly a trend that was massively accelerated by the recent COVID pandemic, which saw shoppers having little choice but to get products they wish to purchase delivered to their homes. While not for everyone, the convenience it brings to many people is readily apparent – browse, select, and pay for products from the comfort of your home and then have the option to have them delivered to your doorstep, sometimes within an hour – what’s not to like?

For many retailers it has driven a dramatic shift in the way in which they need to operate if they are to succeed, not least providing shoppers with much greater flexibility and choice in how they access products and services. However, giving customers more flexibility inevitably creates greater retail complexity, which in turn can increase the risk of retail losses occurring. While we have become all too familiar with the way in which these losses can happen in physical retail stores, the same cannot be said for the losses happening in the ‘virtual’ world of E-commerce. For many retailers, this is the ‘new frontier’ of loss prevention – getting to grips with the risks associated with their online businesses.

This research, therefore, is focussed upon developing a better understanding of how retail businesses are affected by losses in the E-commerce space. In particular, it develops a definition of E-commerce loss that differentiates between outcomes and events considered to be the ‘costs’ of doing business, and those which can be regarded as ‘losses’; identifies, categorises, and defines the range of losses associated with an E-commerce Loss Typology, ensuring that they are manageably measurable and meaningful to as broad a range of retail environments as possible; and establishes a framework for how the financial cost of retail losses stemming from E-commerce activities can be calculated, taking account of the often-different retail formats in operation.

Taken together, this study will enable the retail sector to develop a more comprehensive and overarching appreciation of how business profitability is impacted by loss and how to establish more sustainable preventative strategies in the E-commerce space.

Foreword

Shopping online is now a big and ever-growing part of our retail world, and certainly a trend that was massively accelerated by the recent COVID pandemic, which saw shoppers having little choice but to get products they wish to purchase delivered to their homes. While not for everyone, the convenience it brings to many people is readily apparent – browse, select, and pay for products from the comfort of your home and then have the option to have them delivered to your doorstep, sometimes within an hour – what’s not to like?

For many retailers it has driven a dramatic shift in the way in which they need to operate if they are to succeed, not least providing shoppers with much greater flexibility and choice in how they access products and services. However, giving customers more flexibility inevitably creates greater retail complexity, which in turn can increase the risk of retail losses occurring. While we have become all too familiar with the way in which these losses can happen in physical retail stores, the same cannot be said for the losses happening in the ‘virtual’ world of E-commerce. For many retailers, this is the ‘new frontier’ of loss prevention – getting to grips with the risks associated with their online businesses.

It is for that reason that ECR Retail Loss commissioned Professor Beck to undertake research focussed upon developing a better understanding of how retail businesses are affected by losses in the E-commerce space. This included developing a typology of E-commerce losses that the industry can use to help identify, categorise, and measure the various losses occurring in this form of retailing. Like his work on Total Retail Loss, we hope this study will enable the retail sector to begin to develop a more comprehensive and overarching appreciation of how business profitability is impacted by loss and help to develop and establish more sustainable preventative strategies in the E-commerce space.

As ever, we are very grateful to Professor Beck for carrying out this research and to the numerous retailers who agreed to participate in his research – your time and knowledge is much appreciated.

Finally, can I encourage you to not only read and share this study, but also take part in the work of ECR Retail Loss – further details can be found at: www.ecrloss.com.

John Fonteijn

Chair of the ECR Retail Loss Group

Background and Context

Rise of E-commerce

It is no exaggeration to say that one of the most significant changes in the world of retailing in the past 50 years is the rise of online shopping/E-commerce – the capability for consumers to use a computer with a connection to the Internet to browse, select, pay for, and have delivered to their homes almost any product they want, sometimes within an hour1 . It seems not that long ago that the act of shopping was intrinsically bounded by physical proximity to Bricks and Mortar stores, with product availability limited to what a retailer in any given geographic area wanted to provide2 . Now, many shoppers have access to a global market – they can ‘move’ between retailers (often registered in different countries) at the click of a button, searching out ‘better’ deals for products and services.

For many retailers this has had at least two profound effects: 1) dramatically increased competition; and 2) significantly increased operating complexity. This is perhaps epitomised by the growth of ‘Omni-channel’ retailing – businesses giving their customers multiple shopping pathways to obtain the products they want/ need, such as By Online Pick-up in Store (BOPIS); and Buy in Store Deliver to Home (BSDH)3 . This is super convenient for the shopper and may encourage them to be more loyal to the provider, but, in terms of retail operations, a step change in complexity compared with the traditional ‘Mono-channel’ form of retailing.

Given the convenience of E-commerce retailing, it is perhaps unsurprising that the percentage of retail sales it accounts for has grown over time, especially in some countries with favourable geography (large population centres and small travel distances between them) and highly competitive retail sectors (such as Grocery in the UK). For instance, in Western Europe, E-commerce sales have grown by 116% from 2015 to 20225 . As a proportion of all retail sales, E-commerce now accounts for 15% in Western Europe, with the UK having the highest proportion – 26.5%. In the US, E-commerce sales accounted for 19% of total retail sales in 2022, a 100% increase since 2012. Globally, the E-commerce market is considerable, $5.7 trillion in 2022 and estimated to grow to over $8 trillion by 2026 .

As is now well documented, the global COVID Pandemic further turbo-charged the growth of E-commerce retailing because of the forced closure of large swathes of retailing and the imposition of movement restrictions upon populations7 . For many shoppers, the only option to purchase retail products was via online platforms and have them delivered to residential properties. This had three significant outcomes: 1) a tremendous surge in the volume of e-commerce orders (at one point in the UK E-commerce sales reached 35%)8 ; 2) an acceleration in the number of retailers offering E-commerce platforms, often established very quickly with little understanding of how associated risks should be controlled; and 3) the dislocation of existing controls and processes, such as verifying deliveries and checking returns.

While the end of the Pandemic has seen rates of growth in E-commerce in many countries drop back to pre-Pandemic levels9 , it is evident that this is now a major form of retailing across very many countries, with the success and failure of a significant proportion of retailers intrinsically connected with their capability to manage and control their Omni-channel operating environment.

Emerging E-commerce Risk Landscape

The growth of E-commerce has also brought about the emergence of a new range of risks that can negatively impact upon retail profitability – a broadening of the retail landscape of loss, requiring those tasked with its management to develop new knowledge, skills, and methods of control. While there is certainly some overlap with the types of risks found in Bricks and Mortar stores, it is also becoming evident that E-commerce presents some unique challenges and indeed opportunities when it comes to managing those risks.

For instance, the scale of E-commerce and the number of potential bad actors is profoundly different compared with traditional forms of retailing – limitations imposed by geographical proximity and store ‘opening times’ no longer apply – offenders can ‘access’ a retail business both nationally and increasingly internationally, 24/7, significantly increasing the size of the potential offender ‘pool’. In addition, the nature of the Internet environment and capacity to share information quickly and widely can expose retail businesses – knowledge about scams and loopholes can spread fast, generating significant financial vulnerabilities10. For instance, while one or two local thieves may share knowledge about the temporary absence of say a security guard in a local store, offering opportunities for shop theft, the E-commerce equivalent could be the disclosure of a pricing loophole/mistake via social media, which is then read and acted upon by tens, possibly hundreds of thousands of people.

More positively, E-commerce retailing is proving to be a comparatively data rich operating environment – consumers/thieves/opportunists frequently leave detailed data trails that can offer powerful insights into the nature and scale of the problem, and the effectiveness, or not, of interventions used to try and control associated risks. Indeed, it is difficult to achieve the levels of anonymity offenders enjoy in Bricks and Mortar stores when operating online – electronic footprints are usually left behind, offering those tasked with detection and prevention valuable data points to act upon.

Current Estimates of E-commerce Losses

To date, the majority of available data on the extent to which retailers are being impacted by E-commerce related losses is largely limited to issues associated with malicious forms of loss, such as incidents of fraud, and the costs relating to Chargebacks11. For instance the Merchant Risk Council (MRC) regularly publishes the results from their Global Fraud and Payments Survey12. This data includes retailing along with other sectors, covering major markets across the globe. The 2022 survey estimated that globally, survey participants had lost 3.6% of revenue to payment fraud (up from 3.1% in 2021), with 3.1% of orders becoming a Chargeback issue.

Another study suggests that E-commerce losses globally due to online payment fraud will exceed $48 billion in 2023, up 16% from the previous year13. As will be described later in this report, the proposed E-commerce Loss Typology covers a much broader range of losses than just payment fraud, including the issue of Returns, for which there are also some data sources available14. For instance, the National Retail Federation (NRF) in the US publishes annual surveys on the cost of retail returns, including those from online sales. In their 2022 survey they estimated that of the $1.29 trillion of online sales, 16.5% will generate a return ($212 billion), of which $22.8 billion (10.7% of returns) will be considered fraudulent.

Establishing a More Comprehensive E-commerce ROI

We are all familiar with the partial/selective use of statistics to support a particular outlook or business proposition, especially when relevant data sets can be hard to collect, collate, and analyse. Self-checkout systems (SCO) in retailing are a good example17. If their introduction is measured simply in terms of labour saving, especially in Grocery retailing, then it is hard not to conclude that it is a brilliant business choice with a profoundly positive ROI. However, when hard to get loss data associated with SCO systems is put into the ROI mix (as well as other measurable costs), then the picture becomes much more nuanced, with some retailers withdrawing certain types of SCO system because they do not make financial sense – they are either losing more than they are saving or at the very least, not achieving the returns first envisaged.

Developing the capability to achieve this more rounded ROI, especially when it comes to accounting for the negative outcomes of a retail business decision – the losses that may be generated/profits and margin not realised – requires a much more developed understanding of, and capability to measure, these outcomes. This is where the need for a detailed typology of loss19 becomes important – what are the various ways in which a business is incurring all forms of loss (stock, margin, and sales) and how should they be measured to capture the value? This can then enable a retail business to properly evaluate the efficacy of any given business choice – when all things are considered, does it make a sufficiently positive contribution to business profitability, for instance how does the Internal Rate of Return compare with other initiatives?

The Challenge of Measuring E-commerce Losses

The evolution of E-commerce retailing represents a significant new challenge to the retail loss prevention industry, not only because it typically adds organisational complexity, which in turn can provide new opportunities for loss to occur, but also because it generates new forms of risk in new settings as well, such as cyber space, or even more mundanely, outside a consumer’s house. Whereas ‘traditional’ forms of loss experienced in retail stores have been thoroughly defined and understood, not least in the various iterations of the Total Retail Loss Typology, the same cannot be said for the E-commerce environment.

In some respects, this is understandable; it takes time for new risks to emerge and methods to be established to define and measure them. But, without this taking place, those tasked with responding to, and controlling these new risks, will remain in the dark. Just as ‘traditional’ loss prevention teams moved from what was once regarded as myopically operating in a data desert with little understanding of the organisation-wide impact of loss, those tasked with getting to grips with the negative outcomes of E-commerce retailing now need to go on a similar journey.

Research Objectives

- The research presented in this report had four main objectives:

- Review the way in which retailers currently define and measure losses associated with their E-commerce activities.

- Develop a definition of E-commerce Loss that enables the industry to better understand the difference between outcomes and events considered to be the ‘costs’ of doing business, and those which can be regarded as ‘losses’.

- Identify, categorise, and define the range of losses associated with an E-commerce Loss Typology, ensuring that they are manageably measurable and meaningful to as broad a range of retail environments as possible.

- Establish a framework for how the financial cost of retail losses stemming from E-commerce activities can be calculated, taking account of the often-different retail formats in operation.

It is important to note that this report is not looking at nor evaluating the various ways in which retailers are controlling their E-commerce-related losses – it is not a review of preventative best practice. Its purpose is to provide the industry with a rationale and framework for how it can begin to categorise and value losses associated with E-commerce-related activities. No doubt future ECR Retail Loss research will focus upon how E-commerce losses can best be managed and controlled.

Methodology

Given the overarching aims and objectives of this study, it seemed appropriate to utilise qualitative research methods. Initially, a literature review was undertaken to understand how retailers and industry bodies were currently describing E-commerce-related losses and especially issues relating to the definition, management and control of fraud and the associated issue of Chargebacks, which have largely dominated the E-commerce loss agenda thus far.

The research then proceeded using detailed interviews with retail representatives who had responsibility for E-commerce-related activities and/or controlling losses. These were secured through links provided by ECR Retail Loss, a representative body of global retailers and product suppliers, and the Retail Industry Leaders Association (RILA) in the US. Prior to starting the project, ECR Retail Loss had established a specific working group on E-commerce, which holds regular online meetings to discuss relevant issues. This group was especially useful in gaining access and permission to interview retail representatives. In addition, the project was publicised via the social media site Linked-in, inviting interested retailers to participate.

In total, 14 companies agreed to take part and offer interviews – eight in the US and six in Europe. The businesses varied considerably in terms of size, mode of operation, and experience of controlling E-commerce operations – some had invested heavily in E-commerce-related loss control teams while others had only just begun to establish any form of strategic plan.

All the interviews were carried out online - some were one-to-one while others were done in small groups, with the average interview time being approximately 55 minutes. Respondents were sent a list of questions in advance, and these were used to guide the interviews although opportunities were provided throughout for them to explore issues of E-commerce-related loss as they understood the term from their perspective and business function. All interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed for analysis. To preserve the anonymity of those taking part in the research, any direct quotes from interviews will only be identified with a Research Response number (RR**) rather than the name of the company and the respondent.

Because of the researcher’s experience of working on the Total Retail Loss Typology, a similar approach was adopted, focused upon using a set of rigorous research procedures that allowed the conceptual categories of E-commerce loss to emerge as the research progressed. Initially, respondents were given the opportunity to describe their main areas of ‘loss’ and how they defined and measured them, and then as common themes were identified, follow-up meetings were carried out to ‘test’ the efficacy of the emerging framework.

Notes of Caution

Whenever a research project employs qualitative methods questions arise about the representativeness of the information that has been collected. By using both ECR Retail Loss and RILA, the choice of participating retailers was largely limited to those who were members of these groups. These are typically large retailers and, in the case of ECR Retail Loss, predominately Grocers. Therefore, the views of smaller retailers are largely absent from this research as are the views of some specialist retail companies and businesses not operating in the US and Europe. As with any research on commercial organisations, access is always problematic for researchers – they are wholly reliant upon those companies that are willing to participate, and their views will inevitably feature prominently in the final analysis. However, by utilising retailers from across both the US and Europe, it is hoped that the results are largely representative of a reasonable range of retailers that are operating E-commerce retailing.

Establishing an e-commerce loss framework

This section of the report maps out the key findings from the study, focussing upon the following areas:

- How to define E-commerce-related losses.

- The various sources of data typically available to retailers.

- Identifying the ‘location’ of E-commerce losses within the business.

- Categorising E-commerce losses: Known and Unknown, and Malicious and Non-malicious.

- Putting a value on E-commerce losses.

Defining E-commerce Losses

Within the realm of retail loss prevention and control, there has been much debate about the nature and scope of its work and how it should be defined. This is perhaps best exemplified by the ongoing reliance by many retail businesses on the term ‘shrinkage’ to measure their losses and define their scope of activity. But, as detailed in the various reports on the development and use of ‘Total Retail Loss’ (TRL), the term ‘shrinkage’ has never enjoyed an agreed and clearly articulated definition – it has been used as a generalised catch-all word, differing in nature and scope from one retailer to another.

For some it is only a measure of unaccounted for stock, while for others it can include a myriad of profit eroding events, such as price mark downs, damaged goods, and incorrect pricing to name but a few. As such, ongoing industry benchmarking exercises using this term have always been fraught with ambiguity, especially when markedly different types of retailing are combined. It is an important part of this research, therefore, to provide a framework for thinking about what can be defined as E-commerce losses.

There are two areas for consideration: the first is deciding what is covered by the term ‘E-commerce’ and the second is what is meant when using the word ‘Losses’.

The Scope of E-commerce

The term ‘E-commerce’ is now regularly used throughout retailing to describe the sale of goods and services via a computer interface utilising the Internet. Other terms are also routinely used, such as Digital Retailing, and Online Retailing, which typically refer to the same concept, which is shoppers being able, using computers networked via the Internet, to browse, select, pay for, and receive retail products.

There are also two related terms which are often discussed when considering E-commerce – Omni-channel or Multi-channel retailing. It is important to understand that these are a different concept, often incorporating E-commerce, but not acting necessarily as an alternative descriptor. Both Omni-channel and Multi-channel retailing typically refers to a form of retailing whereby consumers are given a range of sometimes interconnected ways in which they can browse, select, pay, and then receive goods they wish to purchase (including returning products as well). For instance, customers could choose to buy a product via an online portal provided by a retailer but elect to pick up that item at a physical store. Alternatively, they could do the same but complete all the steps exclusively while in a retail store. Equally, they could choose a channel of shopping whereby they select and pay for their items online and the retailer arranges for the goods to be delivered to their home or a third-party location. In other words, Omni-channel/Multi-channel describes the provision of consumer choice in how to shop while E-commerce relates specifically to the utilisation of an online shopping portal by consumers.

For the purposes of this report and its associated typology, the term E-commerce is used to describe when a shopper has elected to purchase products via an online portal and then receive those items either by direct delivery to a chosen address or an agreed third-party location, or arrange a pick up at a retail store.

Defining E-commerce Loss

The current research is premised upon the theoretical developments concerning defining retail loss drawn up as part of the work on Total Retail Loss (TRL)23. This work created a useful distinction between what is a retail ‘loss’ and what can be regarded as a legitimate retail ‘cost’. This enables a much more defined approach to both categorising various forms of retail loss and how they can be valued. Below is an adapted version for the purposes of this report:

Costs: Expenditure on activities and investments that are considered to make some form of recognisable contribution to generating current or future retail income via an E-commerce platform.

Losses: E-commerce-related events and outcomes that negatively impact retail profitability and make no positive, identifiable, and intrinsic contribution to generating income.

Using these definitions, various types of E-commerce-related events and activities can begin to be categorised accordingly. For example, incidents of customer fraud (e.g., goods received using a stolen credit card) can clearly be seen to be a loss – the event and outcome plays no intrinsic role in generating retail profits – it makes no identifiable contribution whatsoever and were it not to happen, the business would only benefit.

Alternatively, incidents of customers returning a perfectly resalable item is a cost – managing returns is an accepted part of the costs of a retail business, especially one operating online. Another example of a loss would be an order not being physically received by a customer – the items have gone missing in the process of delivery. This action has no intrinsic value to the retail business whatsoever and is therefore a loss as it will undoubtedly negatively impact upon business profitability (e.g., duplicate items will have to be reshipped to the customer).

Customer Appeasement: Cost or Loss?

Based upon this definition of loss, it is possible to begin to identify a series of E-commerce-related causes of losses and to exclude others that can be viewed as a cost of doing business. However, there is another category of events/outcomes that negatively impact upon business profitability that could straddle both costs and losses as defined above. These are the planned and unplanned activities and behaviours, often by customer service teams and others in the business which, strictly speaking, negatively impact upon overall retail profitability, but nevertheless, can be seen as having a beneficial role to play in helping the business generate current and future profits, and hence can be seen as a cost.

For instance, offering a customer who is unhappy with the quality of a product they have received a discount on the price paid or a voucher to reduce the cost of a future purchase. Another could be replacing an unavailable item with a similar one that might cost more (e.g., one variety of cooking oil with another). These can be viewed as Cost-related Appeasements – these business ‘choices’ can be regarded as investments in goodwill, to try and ensure that recipients continue to be customers in the future and so can be defined as a cost.

However, the current research has also identified Loss-related Appeasements, especially by customer service teams, where the Appeasement is carried out as a direct result of a loss event. If the loss had not occurred, then the associated Appeasement would not have been necessary. For instance, a Goods Lost in Transit event occurs and in addition to agreeing to replace the lost items, the customer is also given a percentage discount on the items being purchased. In this instance, the value of margin loss caused by the discounting practice would be considered a Loss-related Appeasement and should therefore be included in the overall loss value.

Sources of E-commerce Loss Data

It is important to recognise that the typology of loss offered in this report is not meant to be an exhaustive list of all the various ways in which E-commerce activities can generate losses – it is not being put forward as a comprehensive catalogue of causes. The typology is much more focussed upon developing a series of causes of loss that are most likely to be manageably measurable within different types of retail businesses offering E-commerce retailing25. This is based upon the interviews carried out as part of this research and previous ECR Retail Loss online events and feedback sessions26. As with the TRL typology, retail businesses will be at different stages of maturity in the way in which they are able to define and measure their E-commerce-related losses – some will only be able to measure a small number of identified causes of loss, while others may be much more established in their data collecting processes.

In addition, the way in which a retailer organises its E-commerce activities will also affect its capability to collect, collate and analyse data relating to losses. For instance, retailers utilising their existing estate of physical retail stores to act as mini-fulfilment centres may well find it much more difficult to track outbound and returning products than a retailer with a single E-commerce-focussed fulfilment centre.

It may also be further complicated by the distribution of E-commerce-related responsibilities within a business, for instance, the Supply Chain function may take responsibility for managing returns, Finance may receive details of the costs of Chargebacks, while Loss Prevention could be leading on fraud management and Chargeback dispute resolution. This web of responsibility and fragmentation of data sources can make populating an E-commerce Loss Typology less than straightforward for some businesses. As such, the current Typology should be viewed as an initial and evolving methodology that can be adapted and tailored to the needs of any given retailer – to be used as a tool to better understand their own landscape of E-commerce-related losses and how it might compare with other channels of activity such as Bricks and Mortar retailing.

Key Sources of E-commerce Data

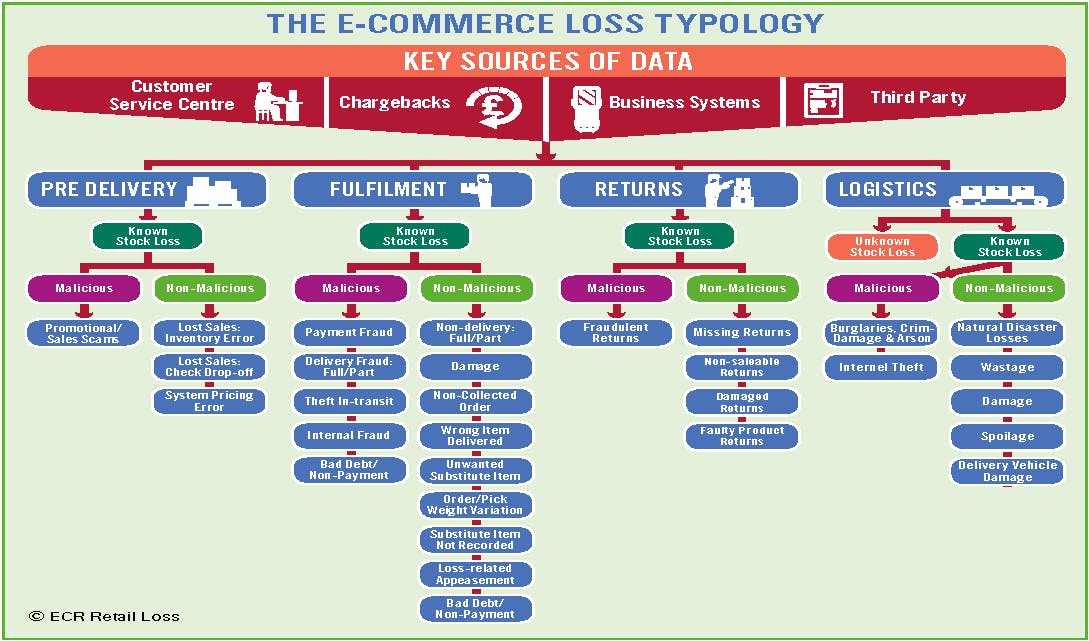

The research has identified four main sources of data for understanding E-commerce losses: Chargebacks; Customer Service Centres; E-commerce Business Systems; Third-party Organisations.

Chargebacks

Currently, this is probably the most dominant source of data for many retailers when it comes to measuring their E-commerce losses. Indeed, for some respondents to this research it was almost the equivalent uni-dimensional measure of loss as ‘shrinkage’ is in the world of Bricks and Mortar retailing. As one retailer put it: ‘[we] only use chargebacks as a measure of loss for E-commerce at the moment – everything else is scattered around the business’RR12. It is easy to see why this might be the case – Chargeback data is usually clearly identifiable within a business as an E-commerce related loss – the value of the transaction is taken back from the retailer and a service charge is applied by the issuing bank/financial institution. However, the value of the loss may well vary depending upon whether the retailer records the associated products at cost or retail prices and whether shipping costs are included in the transaction value (see below). In addition, retailers will also be offered a ‘reason’ code for the Chargeback which can be used to further categorise the types of loss experienced.

Customer Service Centres

A second key source of E-commerce-related loss data can be from a Customer Service Centre. Some retailers employ teams of staff (internal and external) to respond to customer queries about their E-commerce orders and experience. Indeed, for some respondents to this research, this service was an important mechanism for minimising the number of Chargebacks they incurred: ‘keeping customers informed and getting missing orders reshipped stops some Chargebacks from happening’RR7. Various types of losses can be recorded in these Centres, not least missing orders and products, wrong item deliveries etc. As detailed above, Customer Service Centres can also generate cost and loss-related Appeasements, which may take the form of discounting, refunding and voucher issuing.

E-commerce Business Systems

The third source of data are the various business systems that may well record aspects of the E-commerce journey, not least at the point of order (such as pricing errors and customer drop off rates), the fulfilment process (such as internal fraud), the returns process (such as identifying damaged returns); and the management of the logistics operation (such as recording damage and spoilage in fulfilment centres). One respondent neatly summarised this issue: ‘There are a lot more moving parts in E-commerce that can generate losses – we need to access multiple data points to understand what’s going on’RR10. The extent to which these systems will identify E-commerce-related losses will vary tremendously between retailers depending upon how they have been established and the extent to which E-commercespecific activities can be distinguished from other retail channels. For instance, where existing retail supply chain centres provide stock to both retail stores and fulfil online orders, it is highly unlikely that any losses incurred will be able to be associated with a given type of retailing.

Third-party Organisations

The final potential source of E-commerce-related data are third-party agencies and organisations that might be used to identify and categorise various types of losses. There are now very many organisations operating to help retailers manage their E-commerce sales and risks – some proffer risk assessment tools, others help mitigate Chargebacks issues, while some will work with retailers to try and reclaim disputed claims, such as through Civil Recovery, Chargebacks dispute resolution and Arbitration services. In addition, shipping companies may also be able to provide data, particularly relating to problems with customer delivery claims. While most of these organisations focus upon prevention and loss recovery, they can also provide data on actual losses and how they can be categorised within the proposed typology.

‘Locating’ E-commerce Losses

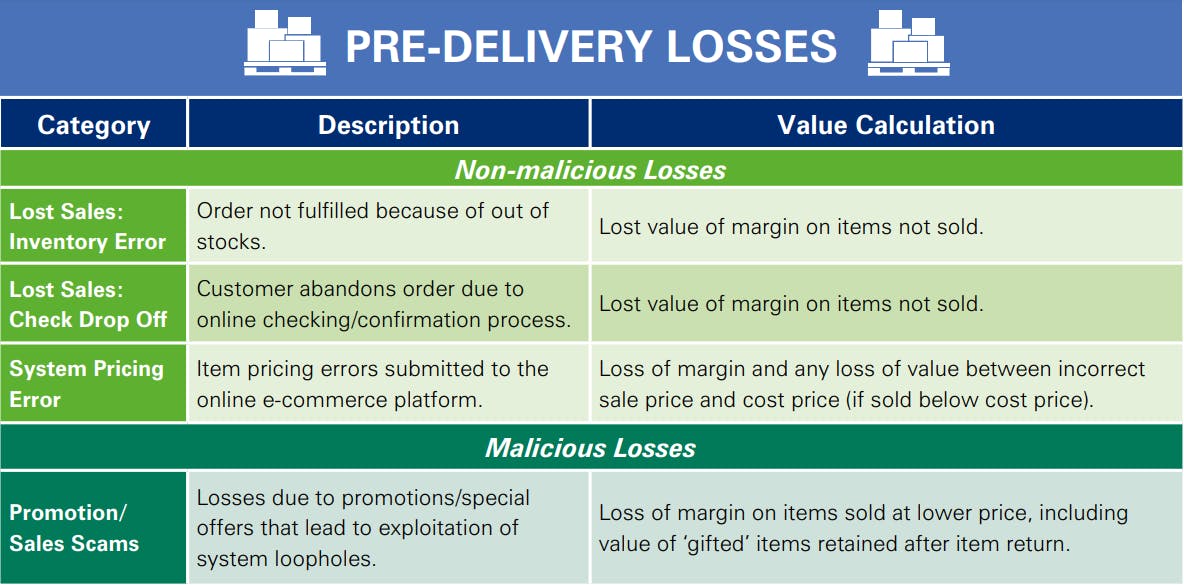

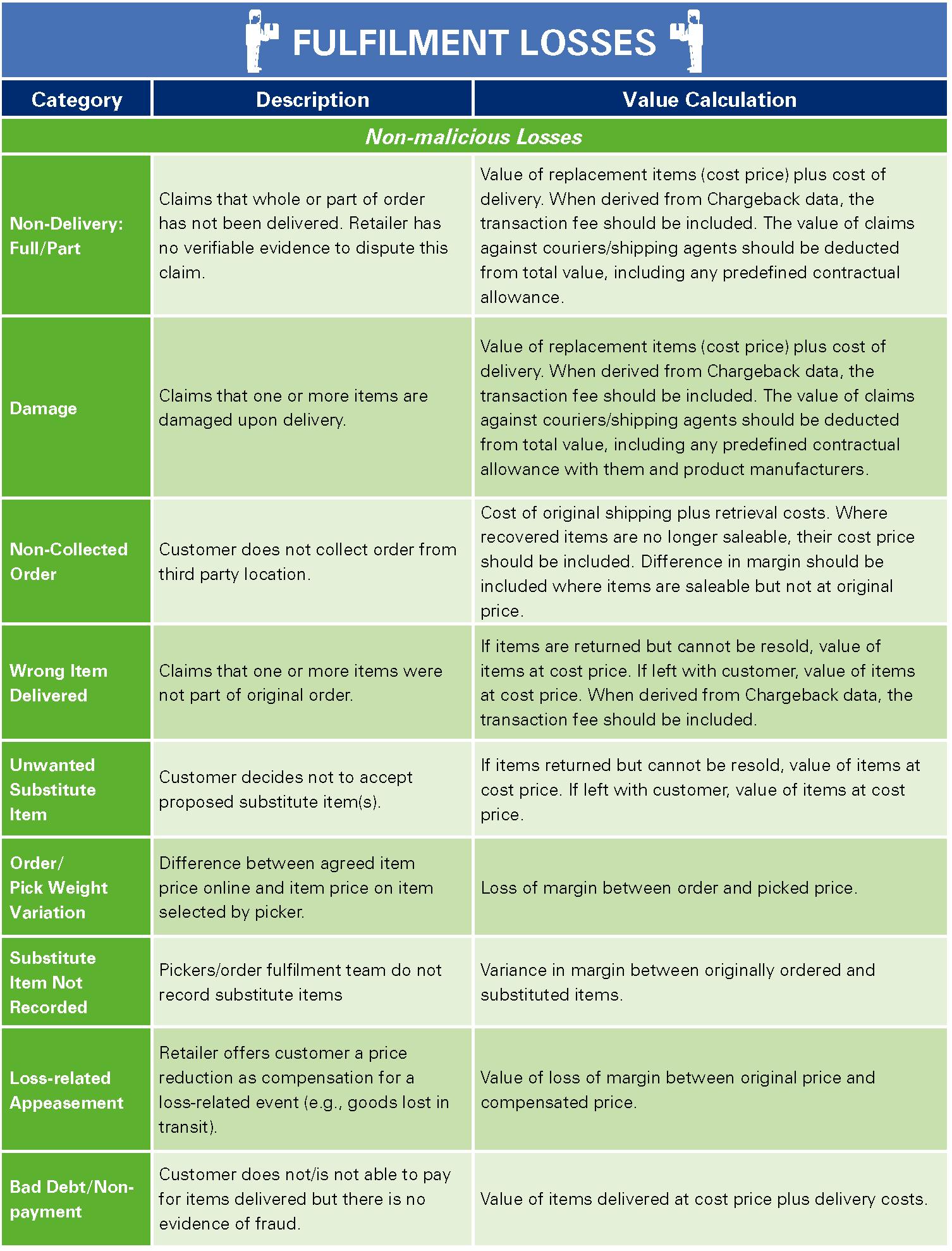

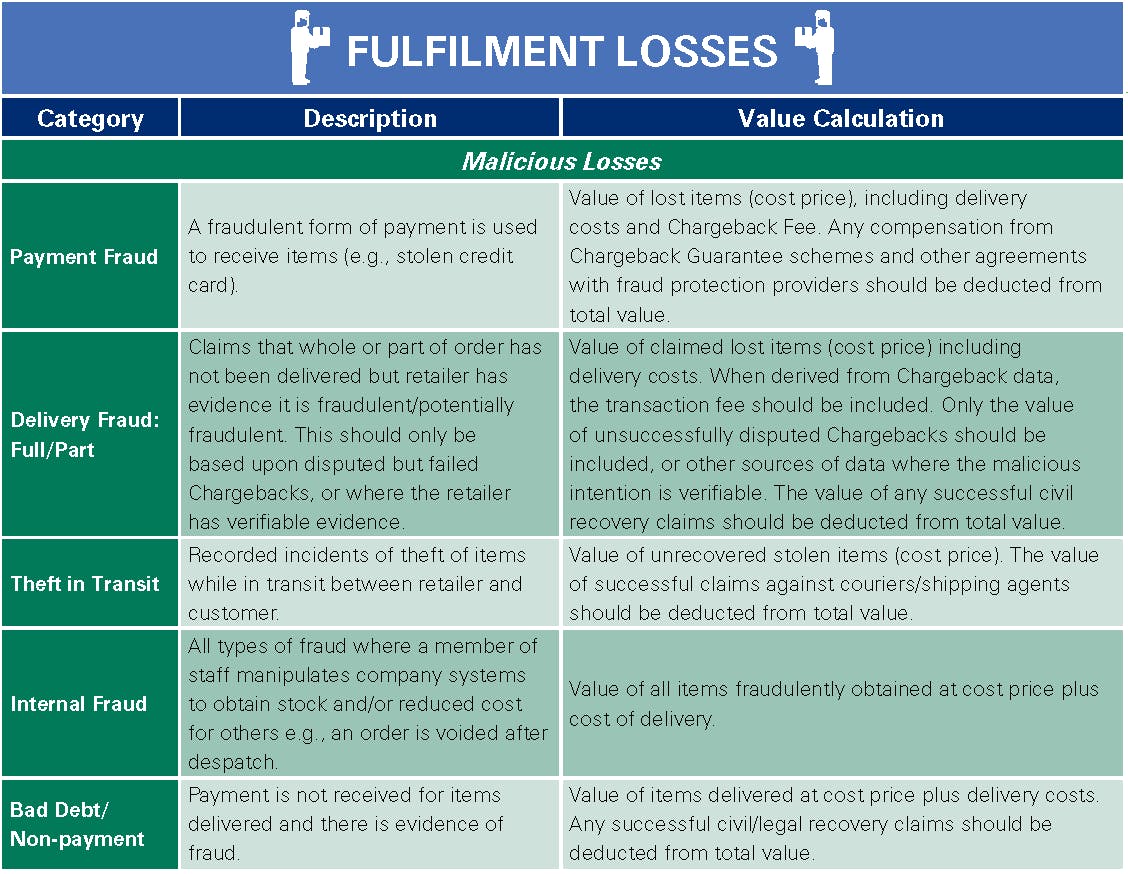

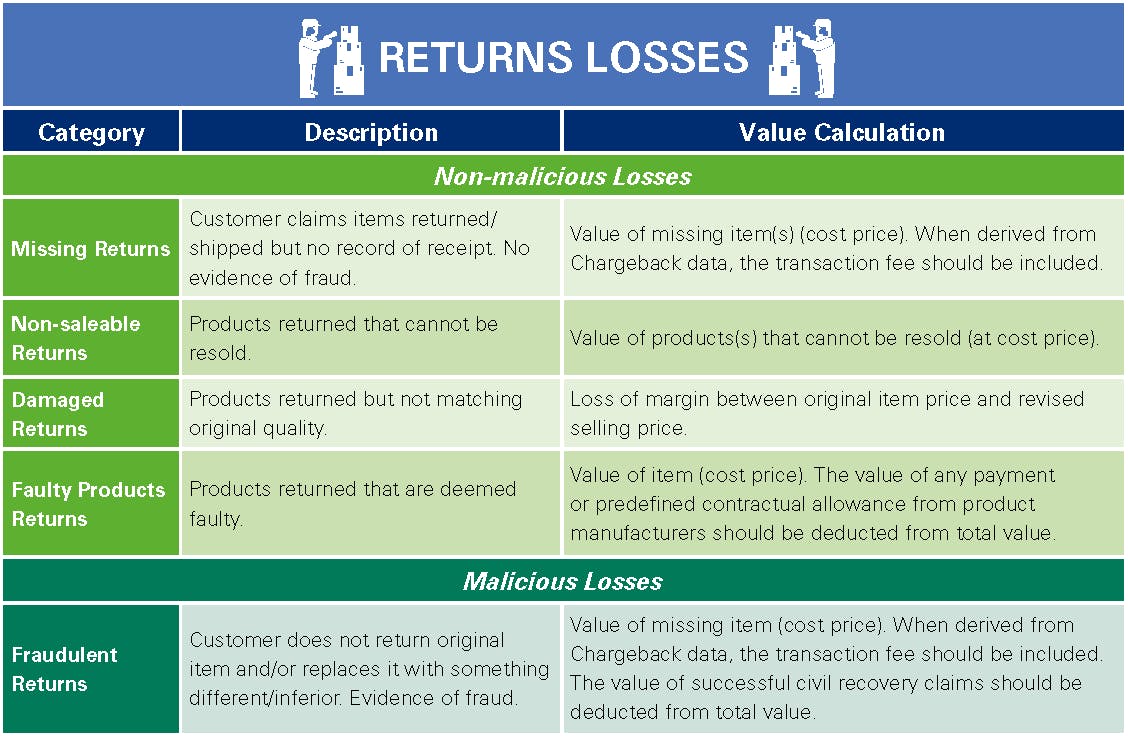

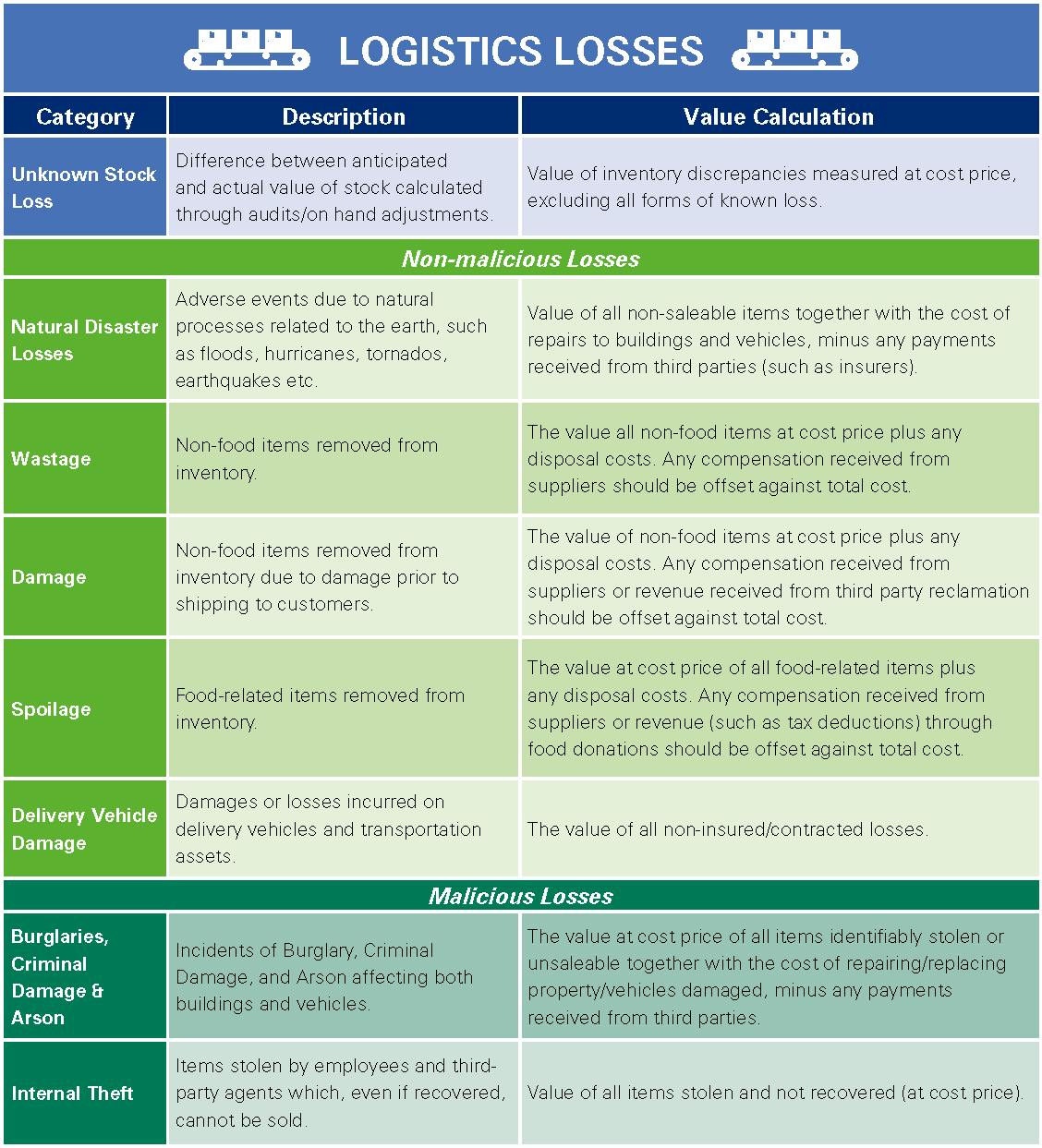

As will be described below, the proposed E-commerce loss typology has identified 30 potential categories of loss, and these have been organised in to 4 discrete areas of retail activity: Pre-delivery; Fulfilment; Returns; and Logistics.

Pre-delivery refers to losses that are generated before or regardless of whether items are sent out of a retail business.

An example would be the value of orders that are lost due to customers not successfully completing a 3D Secure step (Check Drop Offs) or where there has been a pricing error and stock has been offered for sale at a lower price than originally planned.

The second category of retail activity is Fulfilment, which accounts for 43% of all the current categories of loss. This primarily covers the range of losses that relate to loss of stock, such as customer fraud (identified after items being shipped), items lost/stolen in transit, and issues relating to the items shipped (wrong item sent, substitute item not wanted or not recorded etc.).

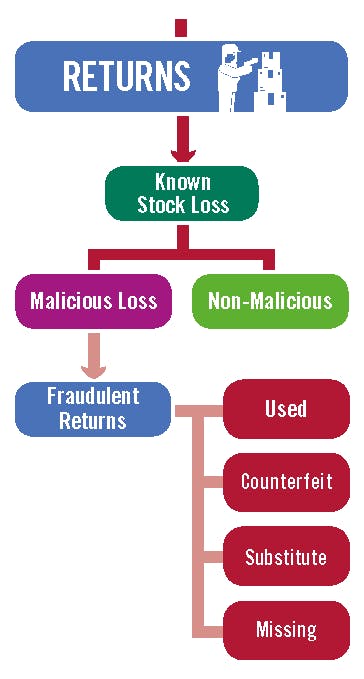

The third area is focussed specifically upon the issue of Returns and how some of these can generate various forms of loss, such as damaged items (reduced margin), non-saleable items, and fraudulent returns.

The final area is focussed upon the issue of retail Logistics and refers to the types of losses that could be recorded in E-commerce-specific fulfilment/supply centres, such as damages, wastage, and internal theft.

Categorising E-commerce Losses

The typology also provides two further levels of differentiation that warrant explanation: known and unknown losses; and malicious and non-malicious losses.

Known and Unknown Losses

One of the differences between typologies developed to categorise losses retailers experience in Bricks and Mortar stores compared with E-commerce, is the extent to which the potential causes of the loss are likely to be known or unknown. One of the significant challenges associated with the traditional ‘shrinkage’ number is that it is largely a measure of stock losses where the cause is unknown, not least because the source of the data is often infrequent stock takes. The auditing process rarely if ever generates data that might give a sense of where, when, or indeed how losses occurred. As such, they are best recorded as Unknown Stock Loss.

However, the E-commerce environment is quite different in the way that transactions and product movements are recorded, and the sources of losses identified. Issues such as customer frauds, products not being delivered, and items being returned damaged are not only brought to the attention of the retailer relatively quickly, but also the transaction data is readily available to enable a value to be calculated. Compared with a Bricks and Mortar environment, E-commerce retailing is extremely data rich, offering far more opportunities for the causes of loss to be known rather than unknown. Indeed, within the proposed E-commerce typology below, the issue of unknown stock loss is only regarded as a relevant category within the Logistics area of retail activity, where traditional stock audits are more likely to be utilised.

Malicious and Non-malicious Losses

Within the category of known retail losses, it is possible to subdivide them into two groups: malicious and non-malicious forms of loss. ‘Malicious’ refers to those activities that are carried out to intentionally divest an organisation of goods, cash, services and ultimately profit, while ‘non malicious’ relates to events that occur that unintentionally cause loss. The importance of understanding the intentionality of a loss occurrence is the impact it has upon the approach adopted to address it and the expected longevity of the results of an intervention. Malicious losses are intentional and occur deliberately with a degree of forethought. To a certain extent such losses occur when existing systems have been found to be vulnerable – sometimes by accident, often by ‘probing’ – and are duly ‘defeated’ by the offender. For example, anti-fraud systems can be defeated with new forms of algorithmic attack, which in turn will need IT/Security Specialists to address them, often at short notice to reduce the impact.

On the other hand, unintentional or non-malicious loss is usually less dynamic and more responsive to lasting ameliorative actions. For example, errors in picking orders can be addressed through various systems changes and interventions (such as scanning outbound packages where RFID is used). Such an intervention is much more likely to have a lasting effect than interventions where a malicious actor is constantly probing for weakness and opportunity. It is therefore considered useful to categorise known losses into malicious and non-malicious to help retail businesses build more responsive and relevant control strategies.

Friendly Fraud?

While most forms of loss can be readily coded into Malicious v Non-malicious, the E-commerce environment has generated an area of loss where the intentionality is sometimes much more ambiguous and certainly open to interpretation. This is the area of claimed/actual non-delivery of some, or all the goods and services requested from a retailer. Very many retailers rely upon third-party delivery companies and product suppliers to ship their orders to the homes of customers or some other agreed pick-up location (such as a local store or secure locker). This process can and does generate numerous problems: items stolen by courier employees; thieves targeting delivery vehicles; items left on doorsteps and in porches being stolen28; items getting damaged; goods delivered to the wrong address; items missing from orders at the point of picking; customers claiming non-delivery when it has been delivered, deliveries not happening on an agreed date; orders being split across several deliveries, customers not recognising a transaction on their billing statement disputing receiving an order etc. As discussed earlier, many of these outcomes can lead to Chargeback claims and calls to customer service, which in turn can generate retail losses.

The issue of customers claiming an item/order has not been delivered is a particular problem identified by this research: ‘in value terms, this [non-delivery claims] is by far our biggest problem – dwarfs everything else’RR2. In theory, the differentiation between malicious non-delivery (fraud) and non-malicious non-delivery/assumed non-delivery (process error/customer mistake – item/order not shipped from retail fulfilment centre or order not arriving in agreed timeframe) should be possible, but it can be extremely hard to know when a customer may be making a malicious claim – can the retailer and courier ‘prove’ through data that the claiming consumer did receive their order?

In addition, for the malicious customer, this sort of claim can be a relatively risk-free endeavour as we are all increasingly familiar with the vagaries of home delivery – receiving wrong or damaged products is a relatively common event29. This type of ‘ambiguous’ outcome has led some in the retail and fraud prevention industry to describe it as ‘friendly fraud’ or ‘first part fraud’30. It is difficult to understand why any form of fraud can be regarded as ‘friendly’ and it is not a term that will appear in the typology proposed in this research, but it does highlight an issue which is vexing retailers in terms of not only categorising a type of loss, but also getting to grips with developing methods to effectively control it31.

As is detailed below, this issue is addressed in the typology by offering a way to categorise non delivery issues as either non-malicious (no available evidence to suggest it was malicious despite retailer concerns) and Delivery Fraud (sufficient evidence available to draw this conclusion about any given event but not able to recover the loss). In this respect, it errs on the side of caution – it is non-malicious unless there is verifiable evidence to conclude otherwise. In the short to medium term, future industry benchmarking exercises may deal with this issue by simply combining the two categories together – Non-delivery Related Losses – and/or, instead of having only two categories of loss – Malicious and Non-malicious, develop a third, perhaps called ‘Ambiguous’.

Putting a Value on E-commerce Losses

As with the term ‘shrinkage’, there is little agreement within retailing as to how the value of losses should be calculated – should lost products be valued at cost price or at retail prices for instance? Should the costs associated with managing losses be included in this calculation, such as utilising a third-party fraud management system or teams to dispute Chargebacks claims? How should the issue of delivery/shipping costs be handled – are they regarded as part of losses or simply a cost of doing business? In addition, should the costs of customer services also be included in the loss calculation?

In essence, there are three main types of loss that a retail business can experience: the loss associated with products going missing or being unaccounted for (such as being stolen), losses generated by intended transactions not occurring (such as due to a product being out of stock), and losses due to retail margin being negatively impacted (such as a damaged returned product being sold at a lower price than originally envisaged).

In the detailed descriptions below for each of the proposed causes of retail loss included in the typology, a recommendation is made about how the value for any given cause should be calculated based upon the likely source of the data, the importance of not double counting, and ensuring that any compensatory mechanisms are recognised, and their value offset against any given loss.

For the most part, it is recommended that lost items are valued at cost price while issues relating to lost sales and margin take account of the sales price at the time of the event. However, it is recognised that for many retailers operating E-commerce platforms, establishing cost pricing to calculate losses may not be straightforward. For instance, very often, the data derived from Chargebacks is likely to be in the form of transaction values (based upon what the consumer paid) and transforming this data back to cost pricing may not be easy. In this situation, especially if any form of industry benchmarking is to take place, an average item margin value may be required to convert these types of losses to an equivalent cost price.

Dealing With Delivery Costs When Calculating Losses

Another confounding factor in developing an industrywide approach to measuring and understanding E-commerce-related losses is how the issue of allocating and accounting for the costs associated with delivering products to customers is dealt with by a typology. As will be seen below, it is proposed that for some types of E-commerce-related loss, additional shipping costs are incurred which should be included in a loss event calculation. For instance, if a customer makes a claim that an order has not been delivered and the retailer decides to reship the order, the loss ought to be calculated as the cost price of the order items re-shipped plus the additional delivery costs incurred – both are legitimate elements to be considered as a loss to the retail business as neither would have been incurred had the loss event not happened.

However, how E-commerce retailers account for delivery costs in their businesses varies considerably. For some, the above calculation would be possible as they allocate shipping costs to each transaction: ‘we have a pretty good system to track our delivery costs and work it out for customer orders’RR14. For others, they have a centralised and generalised delivery contract where costs are not associated with any given transaction: ‘it would be really difficult at the moment – we just have a courier fee account’RR1. Moreover, for some companies the Chargeback transaction value will combine both the item price and any associated delivery costs making it difficult to dissociate these numbers. Further still, some companies offer ‘free’ delivery for transactions over an agreed value – how might this be accounted for when calculating loss?

Currently, there are no easy routes to navigate this complexity – the proposed typology below works on the assumption that discrete delivery charges can be calculated, and this is done partly to encourage the industry to begin to move towards such as approach, but also to offer companies that may be starting out in E-commerce a more nuanced data collection framework for capturing their losses.

In the short term, any industry benchmarking work on E-commerce losses will have to address this issue in perhaps one of two ways: agree to calculate E-commerce losses excluding delivery costs (or only including them where Chargeback data makes their exclusion overly difficult, or, develop an average delivery cost multiplier for those businesses not able to identify them from their current data. Either way, any E-commerce benchmarking will need to take account of this issue, especially if comparisons are to be accurately drawn across several of the categories of loss outlined below.

Taking Account of E-commerce Loss Compensation Pathways

To avoid the issue of overstating the overall value of E-commerce-related losses, particularly when some of the value of the loss may be covered elsewhere in the business, the research has identified a series of ways in which retailers are able to offset their E-commerce related losses. These are the following:

- Ad Hoc Courier Claims: Claims for the value of goods not delivered against contracted shipping agents where the retailer is confident it has verifiable data showing orders were passed on from their supply chain to the courier, but not subsequently received by a customer.

- Supplier Agreements (Couriers): Agree a percentage discount on contract value to cover a specified number/percentage of non-delivery incidents.

- Supplier Agreements (Manufacturers): Agree a price discount to cover the potential return of defective damaged goods.

- Supplier Agreements (Financial Partners): Establish agreements with partner payment providers (e.g., sponsored/branded credit card) where a proportion of Chargeback costs can be offset to a third party.

- Chargeback Disputes/Arbitration32: Make a successful counter claim against a Chargeback issuer and recover withdrawn funds from customer.

- Chargeback Guarantees: Take out a form of insurance with a fraud monitoring third party provider to cover the cost of some Chargebacks. Typically, this only covers where the Chargeback issuing institution believes it is a fraudulent transaction and so will not cover issues such as non-delivery claims.

- Civil Recovery Claims: Make claims directly on customers suspected of committing fraud, such as claiming orders have not been delivered when a retailer is confident that they have. These are often administered by a third party and will include a handling fee in addition to the disputed transaction costs.

As with the issue of delivery costs, this research has found that retailers vary considerably not only in terms of the number of compensatory pathways they employ, but also their capacity to take account of them when calculating their overall losses from various types of E-commerce-related losses. Once again, future industry benchmarking exercises will need to ensure that ‘comparative’ data is properly calculated. For instance, it would not be appropriate to compare retailers on their payment fraud rates (derived from Chargeback data) where one has a Chargeback guarantee in place and excludes this data from their calculation, and another has not.

THE E-COMMERCE LOSS TYPOLOGY

Context

Outlined below is the proposed typology of E-commerce Losses, organised around the four areas of retail activity, dividing them primarily into malicious and non-malicious forms of known loss (except for Logistics where unknown losses could be calculated).

It is important to note that the typology is designed to enable the ‘value’ of losses to be calculated and not the number of loss events – where an associated ‘value’ cannot be calculated or there is no loss of value associated with an incident, this should not be included. For instance, if a customer makes a non-delivery claim and the retail business successfully disputes this claim (via a Chargeback dispute or Civil Recovery), then this value should not be included as a loss. That is not to say that the retailer may still want to record the fact that it has successfully recovered the funds, but that it would not be recorded in the E-commerce Loss Typology33. In this respect the typology is recording the value of actual losses and not their prevalence (how often they happen). However, if in the above example the Chargeback dispute or Civil Recovery route was unsuccessful, then the cost price of the items plus the original delivery costs would be recorded as a Delivery Fraud.

The Typology

Outlined below is a breakdown of the various categories of E-commerce loss, including a short description and a proposed method for calculating the associated loss.

Categorising E-commerce Losses: A Summary

The various categories of E-commerce-related loss utilised in the typology are a product of discussions with a wide range of respondents to this research based upon their experiences of loss. Different types of retailers offering E-commerce platforms inevitably experience losses in a variety of ways, driven in part by the nature of the products they are offering for sale, and the types of systems and operating protocols they have in place. For instance, Grocery retailing experience particular types of loss, such as Order Pick Weight Variation losses, that are unlikely to be seen in other forms of retailing. It is important, therefore, to view the typology as a template and not a comprehensive review of all the possible causes of E-commerce losses. It is derived from detailed interviews with a range of retail organisations operating E-commerce platforms and as such is an amalgam of the most common, and critically, most likely causes of loss that can be manageably measured.

There are of course a multitude of root causes that make up many of the proposed core categories of loss. These will vary depending upon the retailer, but it is hoped that those selected provide sufficient macro analytical capacity to provide value when it comes to understanding the broad landscape of loss within a business. For instance (see Figure opposite), the category of Fraudulent Returns has numerous root causes, not least, items being returned that have clearly been used/worn by the customer (Wardrobing34), counterfeit copies of items returned, substitute items returned (e.g., bricks for mobile phones) and items deliberately not returned at all, but a refund requested/claimed.

The purpose of the Typology at this stage is not to offer micro-level identification of all causes of loss but more to act as an organisational tool to compare the distribution of core categories of loss across a business, which in turn could then stimulate deeper analysis of any given category warranting further investigation. It also offers a stepping stone towards enabling the retail industry to begin to agree a more uniform terminology, ways to identify the true costs of E-commerce losses, and potential categories of loss that can be used to carry out industry-wide benchmarking.

Summary

Understanding the Landscape of E-commerce Losses

In many respects, loss prevention practitioners tasked with managing E-commerce-related losses are in a much more advantageous position than their counterparts working in a Bricks and Mortar retailing environment36. Certainly in the past, the operating landscape for the latter was best characterised as a ‘data desert’, bereft of but the most basic and generalised indicators to help them answer the following key questions: what has gone missing, where, when, how and by whom? Without definitive answers to these questions, the development of preventative strategies always ends up being based upon the shifting sands of guesswork, prejudice, and mythology.

However, within the world of E-commerce, certainly in terms of data, the opposite is often the case. It is frequently characterised as a data rich environment where bad actors are hard pressed not to leave some semblance of a digital fingerprint, and every stage of the customer journey can be analysed and assessed – customers are in effect ‘data slugs’ leaving an indelible trail wherever they shop!

However, this picture is complicated by the way in which E-commerce has evolved for many retailers, particularly those with a Bricks and Mortar heritage. Their E-commerce development journey has often been piecemeal, disjointed, and opportunistic, frequently being bolted on to existing and well-established retail operational structures designed more for the physical than virtual retail world. In addition, the growth of Omnichannel retailing, which, in effect interweaves layers of complexity across both E-commerce and Bricks and Mortar platforms, has made understanding and identifying the emerging risk landscape from this data much more challenging.

As has been found in the realm of Bricks and Mortar-based retail loss prevention, unless a more overarching, inclusive, cross-functional, and cross-organisational definition of retail loss is adopted, which truly maps out its overall impact upon business profitability, approaches to its control and management will likely remain myopic, reactive, one dimensional, and limited. As the work on Total Retail Loss has begun to show, when the definition of loss becomes more inclusive, the opportunities for making a genuinely positive impact upon business profitability become more profound – loss prevention teams really can become ‘agents of change’, viewed more as business partners than a sales prevention function.

Using the E-commerce Loss Typology

This report sets out a potential E-commerce loss typology for the retail industry based upon the current experiences of a range of retailers operating an E-commerce platform. It seeks to offer a framework that recognises the potential sources of data available to retailers and how the various key causes of loss can be organised, defined, and critically, calculated. As with the work on the Total Retail Loss Typology, the devil is often in the detail, especially when the industry wants to undertake some form of benchmarking exercise. Retailing is riven with variance in the way in which types of loss are defined and calculated – just look at the myriad ways in which the word ‘shrinkage’ is used around the world – few retailers adopt the same definition. This report, therefore, offers 30 categories of loss that can be used by businesses to understand their landscape of E-commerce-related losses – it is doubtful, however, that any one retailer would use all of them – the typology should therefore be seen more as a menu than a template.

While the proposed typology could certainly be used in the future for benchmarking across the industry, it is unlikely that many companies would be prepared to share this level of granularity of detail with others, although some of the broader categories of loss, such as Chargeback rates and Non-delivery losses may work, particularly when shared as a percentage of sales/transactions. Its primary utility, at least initially, could be more as a tool for individual organisations to better understand their own landscape of E-commerce-related loss and how it compares against their losses in other forms of retailing, such as Brick and Mortar.

It should certainly be possible to begin to develop a company-specific Total E-commerce Loss number based upon a sum of the value of the various categories of loss calculated, perhaps presented as a percentage of the overall turnover of the business or as a proportion of the overall profit generated. In addition, the typology may well be able to offer real value through businesses developing a better understanding how the various categories of loss compare with each other – what are the main drivers of loss? This can then be used to begin to inform strategy and the allocation of resources.

Identifying Business Responsibilities

As detailed earlier, the proposed typology combines data from across a range of business functions – Loss Prevention, Finance, Customer Service, Supply Chain, and Finance, to name but a few. In this respect there is currently no obvious single ‘owner’ of all the elements of loss that make up the typology – it transcends functional boundaries. However, it is evident from some of the companies taking part in this study that they have begun to create a more overarching E-commerce Team that brings together the responsibilities for many of the categories outlined in this study. It is hoped that the proposed typology will help to guide retail businesses in terms of not only what categories of loss they should consider measuring (and how), but also how this data can drive thinking around an appropriate organisational structure to enable them to be effectively managed. As one respondent bluntly summarised: ‘we need to move managing E-commerce losses away from being a cottage industry’RR1.

For those with existing responsibility for ‘loss prevention’ it may well be the case that they can act as facilitators of this process – bringing together representatives from across the business with an interest in E-commerce to create something like an E-commerce Loss Control Oversight Group. Its task would be to agree how the various types of E-commerce-related losses will be measured, valued, collated, and analysed, and to then use this information to effectively identify priorities, allocate resources and responsibilities, and monitor outcomes.

Next Steps

Current trends suggest that E-commerce retailing will continue to grow both in terms of the number of companies offering it but also its overall value as a proportion of global retail sales. Like other forms of retailing, the risks associated with this type of endeavour will continue to emerge and change over time – like retailing itself, loss prevention is an ever-evolving topic requiring constant adaptation. For many established loss prevention practitioners, particularly those largely schooled in the world of Bricks and Mortar retailing, E-commerce presents a new and challenging environment within which to operate – catching and deterring criminals, and minimising retail loss in a virtual world is often a very different proposition to that found in the physical world.

It is hoped that this report and its associated typology will help the industry to begin to better understand and define the landscape of loss that needs to be controlled. Like the associated TRL typology, it is currently based upon largely theoretical work requiring real world validation. It is therefore proposed that the industry could consider following these next steps:

- Raise awareness across the industry of the proposed E-commerce Loss Typology.

- Encourage a broad range of retailers to ‘try out’ the typology by populating the current categories of loss with available data.

- Undertake a review exercise with a sample of willing companies that have used the typology to understand its applicability.

- Based upon this review, where necessary amend the current typology.

- Identify whether some of the more generic categories of loss can be used for a limited industry benchmarking exercise.

Through this process of engagement, testing and refinement, it is hoped that the E-commerce Loss Typology will begin to add value to retail companies, enabling them to better understand how various forms of loss are having an impact on their businesses so that they can build more effective systemic prevention strategies. This is important because as one sagely respondent to this research succinctly put it: ‘you’re never going to catch your way to profitability!’ RR13.

NOTES

- There are numerous definitions of E-commerce, such as: the trading goods or services using computer networks such as the Internet: Shahriari, S., Shahriari, M. and Ggheiji, S. (2015) ‘E-commerce and it impacts on global trend and market’, International Journal of Research-Granthaalayah, 3(4), 49-55. Others offer a slightly broader definition but essentially refer to the same thing: ‘electronic trading is the advertisement and procurement of goods and services over the Internet’: Wakid, S., Barkley, J. and Skall, M. (1999) ‘Object retrieval and access management in electronic commerce’, IEEE Communication Magazine, 37(9), 74–77.

- Bricks and Mortar is a term often used to describe physical retail stores where customers can go to browse, select, pay and return products.

- There are various terms used to describe the process of buying retail products away from traditional Bricks and Mortar stores as well as the increasing trend to blend the two together. In this report the term E-commerce will be used to describe retail transactions that are initiated by customers via a computer-interface that can lead to products being delivered to their home, a third-party location or be picked up from a retail store. The term Omni-channel will be discussed later in this report. For a thorough review of the development of E-commerce see: Rosario, A. and Raimundo, R. (2021) ‘Consumer Marketing Strategy and E-Commerce in the Last Decade: A Literature Review’, Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 16: 3003-3024, Article Link.

- Depending upon the fulfilment model adopted, it increasingly requires retailers to have a much detailed and accurate understanding of their business-wide inventory – particularly when you are offering customers a ‘guarantee’ that a product will be available for pick up at any given location. It also requires a greater range of customer services (responding to lost and damaged orders) and the capacity to deal with a greater volume of returns, particularly for Apparel retailers.

- Centre for Retail Research (2022), Link to Webpage.

- Centre for Retail Research (2022), Ibid; Statista (2022), Link to Webpage.

- International Trade Administration (No Date), Link to Website.

- One of the respondents to this research graphically illustrated this trend: ‘before COVID, E-commerce was 2% of sales, now it is 20% of sales!’RR5.

- International Monetary Fund (2022), Link to Webpage.

- One respondent described their experience of this: ‘The evolution of online fraud is super-fast and if you do not have the capacity to react quickly, the MO [Modus Operandi] will have been used, exploited, and then moved on before a fix can prevent all the losses’RR7.

- The term Chargeback refers to a demand by a card provider for a retailer to make good the loss on a fraudulent or disputed transaction. For instance, a thief may use a stolen credit card to fraudulently obtain goods and services from a retailer and when the fraud is uncovered by the paying financial institution, it takes the cost of that transaction back from the retailer, including a transaction fee. Chargebacks can also be initiated by retail customers who are not happy with the goods and services they have purchased from a retailer. They can contact their Credit/Debit Card provider and request that they take the value back from the retailer (again, charging an additional transaction fee). As things stand, retailers have little or no control over this process – the reimbursement is instigated by the financial institution, and it cannot be blocked by the retailer. Retailers can dispute the Chargeback – make a counter claim against the consumer and there is also an Arbitration process in place as well. In the view of many retailers, the Chargeback process makes them overly exposed to customers making false claims, such as non-delivery of items when they have arrived – often referred to as ‘friendly fraud’ or ‘first-party fraud’. One respondent was very frank in their assessment of this situation: ‘the banks are so inconsistent/pathetically useless in how they deal with this issue, even when we have rock solid evidence that their customer is a fraudster. The banks are more inclined to find in favour of the customer – it is the least point of resistance for them’RR1.

- The Merchant Risk Council (2022) Global Fraud and Payments Report 2022, Link to Webpage.

- Only limited data is available from this report as most of the results are behind a very expensive paywall: Link to Webpage.

- See Zhang et al (2023) for a review of the different types of fraudulent returns.

- The survey is based upon responses from 70 retailers and was carried out in late 2022. The study also looks at rates of return to Bricks and Mortar stores as well, which, somewhat surprisingly, are estimated to be at the same rate of sales as online orders (16.5%): Link to the Webpage.

- Return on Investment (ROI).

- See the various Self-checkout reports freely available on the ECR Retail Loss website, Link to Webpage.

- There are some examples of retailers removing some or all of their variants of SCO systems, such as Walmart in 2018 (article link) and Wegmans in 2022 (article link) because of heightened concerns about levels of loss associated with them.

- The word ‘typology’ is used throughout this report to describe a way of systematically categorising events, activities, and/or outcomes based upon some form of constructed logic.

- There are two Total Retail Loss reports freely available from the RILA website. The first was published in 2016, which mapped out the rationale and concept of Total Retail Loss: Link to Webpage. The second, published in 2019, provided an update on the evolution of the Total Retail Loss Typology and summary research on the way in which the retail industry was reacting to, and engaging with, the concept: Link to Webpage.

- See Beck (2016) Link to Webpage

- Beck (2016) ibid.

- Beck (2016) ibid.

- It is worth noting that the work on TRL identified a category called ‘Margin Eroders’ which were defined as costs rather than losses – they did make an identifiable contribution to business profitability although many in the industry considered them to be a loss as they often reduced margin. This included product mark downs and end of shelf-life discounting. It also included what is being described here – Customer Appeasements – discounts and ‘free stock’ to maintain customer loyalty and increase the likelihood of future sales. In this report, the term Loss-related Appeasements is being used to describe a subset of Margin Eroders.

- The term ‘Manageably Measurable’ was used in the TRL work to act as a filter to identify those causes of loss that most retailers taking part in the research suggested they could measure in a way that was largely routine and often automated. There are potentially hundreds of causes of retail loss, but many would be extremely difficult to accurately measure, such the impact of the sale of counterfeit goods or losses directly attributable to reputational damage. This research, therefore, focussed upon identifying the core causes of loss that most respondents felt able to measure with existing business systems and data collection structures.

- Many of these sessions have been recorded and can be accessed at: Link to Webpage.

- Here is a useful summary describing the concept of Chargebacks: Link to Webpage.

- Some have begun try and put an estimate on this number: Stickle, B. Hicks, M. Stickle, A. and Hutchinson, Z. (2019) ‘Porch pirates: examining unattended package theft through crime script analysis’, Criminal Justice Studies, Link to article.

- Some have begun try and put an estimate on this number: Stickle, B. Hicks, M. Stickle, A. and Hutchinson, Z. (2019) ‘Porch pirates: examining unattended package theft through crime script analysis’, Criminal Justice Studies, Link to article.

- See this link for a detailed description of the term ‘friendly’ fraud: Link to Webpage.

- Another way to describe some forms of ‘friendly fraud’ is ‘unintentional claims’ – the claimant genuinely believes that an order has not been properly fulfilled when it has, or will be in the very near future. An example of this would be problems with a split delivery directly from a manufacturer. If the consumer believes that part of their order is missing (it did not arrive with the other parts of the order), and there is no obvious communication to this effect, then this can generate a non-malicious claim for the missing piece of the order.

- While many retailers have complained about the ease with which consumers can instigate a Chargeback and the willingness of card issuers to act on their behalf, companies like Visa are bringing in new guidance on what [Compelling] Evidence retailers can submit to dispute a claim, partly in recognition of the growing concern about the number of claims where a retailer strongly believes they are the victim of fraud. This is called CE 3.0 and will come into effect in April 2023.

- This type of data could be an important Key Performance Indicator for those tasked with managing and controlling E-commerce losses.

- This is a common term used in the industry to describe customers using a product before returning it, such as wearing an item of clothing for a special event. At the moment, few retailers routinely categorise their returns to enable them to understand the extent of this issue. See Speights and Hilinski (2005) for one estimate: Link to Website.

- See Zhang et al for research identifying the range of possible ways in which retailers can suffer from returns fraud.

- One respondent to this research summarised it very neatly: ‘The thing I like about online is that I have more data – I can react faster; I [only] get a score card once a year from Bricks and Mortar (the shrink number)’RR14. Another described how E-commerce enabled them to control losses effectively: ‘It’s much easier to control shrink and damages in E-commerce. The reality is that if we have a high-risk customer, we can put enough road blocks in place to eliminate them from shopping in e-com without them ever knowing. I can’t do that in a bricks and mortar store. It’s so much easier in e-com than bricks and mortar, much easierRR8.

Main office

ECR Community a.s.b.l

Upcoming Meetings

Join Our Mailing List

Subscribe© 2023 ECR Retails Loss. All Rights Reserved|Privacy Policy