Collaboration as an effective lever to food waste reduction

Utilising Collaboration to Tackle Food Waste in Retail Supply Chains

Table of Contents:

- Abstract

- Foreword

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Methodology

- Food Waste Collaboration

- - What is Collaboration and Why Collaborate?

- - The Role of (Better) Collaboration in Reducing Food Waste

- - Case Studies in Collaboration

- Understanding the Barriers to Collaboration

- The Strategic Foundation for Collaboration

- - Strategic Fit – Waste Collaboration Fit with Company Strategy

- - Capability Readiness for Waste Collaboration

- Introducing the Collaboration Readiness Self-Assessment Tool

- Pilot Results

- Key Findings

- - 1. Consistency in Results Between Retailers and Suppliers but Differences also Apparent

- - 2. Data Sharing Capability Remains a Key Barrier to Greater Collaboration

- - 3. Strong Correlation Between the Strategic Fit and Capability Readiness

- Indicated Actions and Future Research

- Appendix I: The Three Stages Overview

- Appendix II: Self-Assessment Questions

Languages :

This report, published in 2019, is focused on the way organisations can collaborate to reduce food waste in the supply chain. It highlights the benefits of working together, and the barriers to collaboration. The report introduces a new framework for effective collaboration and presents a self-assessment checklist for organisations to consider adopting when getting ready for a collaboration project. Finally, the report shares the self-assessment data on the readiness of a sample of retailers, presenting some benchmark data and highlighting how the sharing of, and availability data is the most significant barrier to more effective collaboration for this sample of organisations.

It draws upon in-depth interviews and focus groups from representatives of 13 retailers and producers, from UK, Germany, Netherlands, Belgium, Portugal, Czech Republic and Spain. The project team was assisted by the support of academics from Kuenhe Logistics University (KLU) and the Cardiff Business School.

The report highlights five major barriers to collaboration, namely; competing internal priorities, accessibility to data and transparency, food waste not identified in the joint business plan as a priority, failure to reach agreements on benefits sharing and finally, it came down to people, and the constant changes in key individuals central to any collaboration effort, and then the capacity and time to dedicate to a collaboration project.

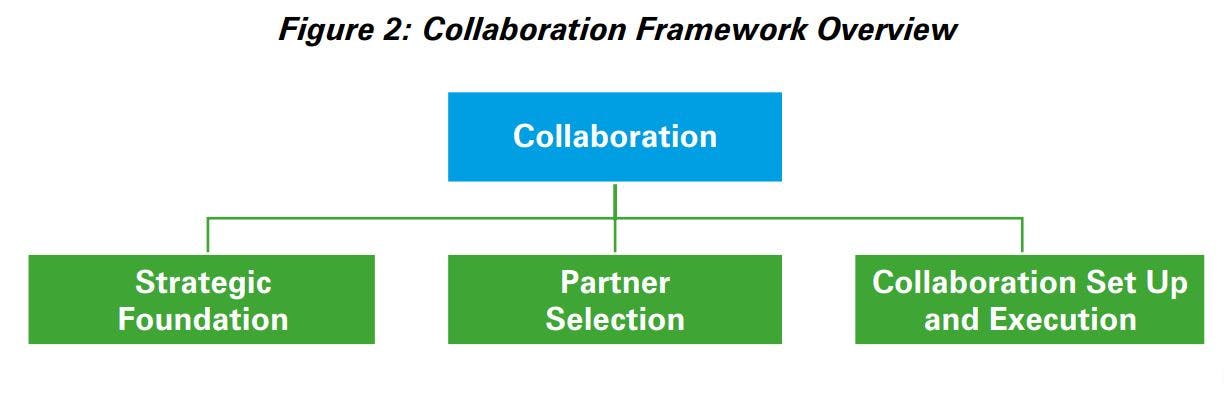

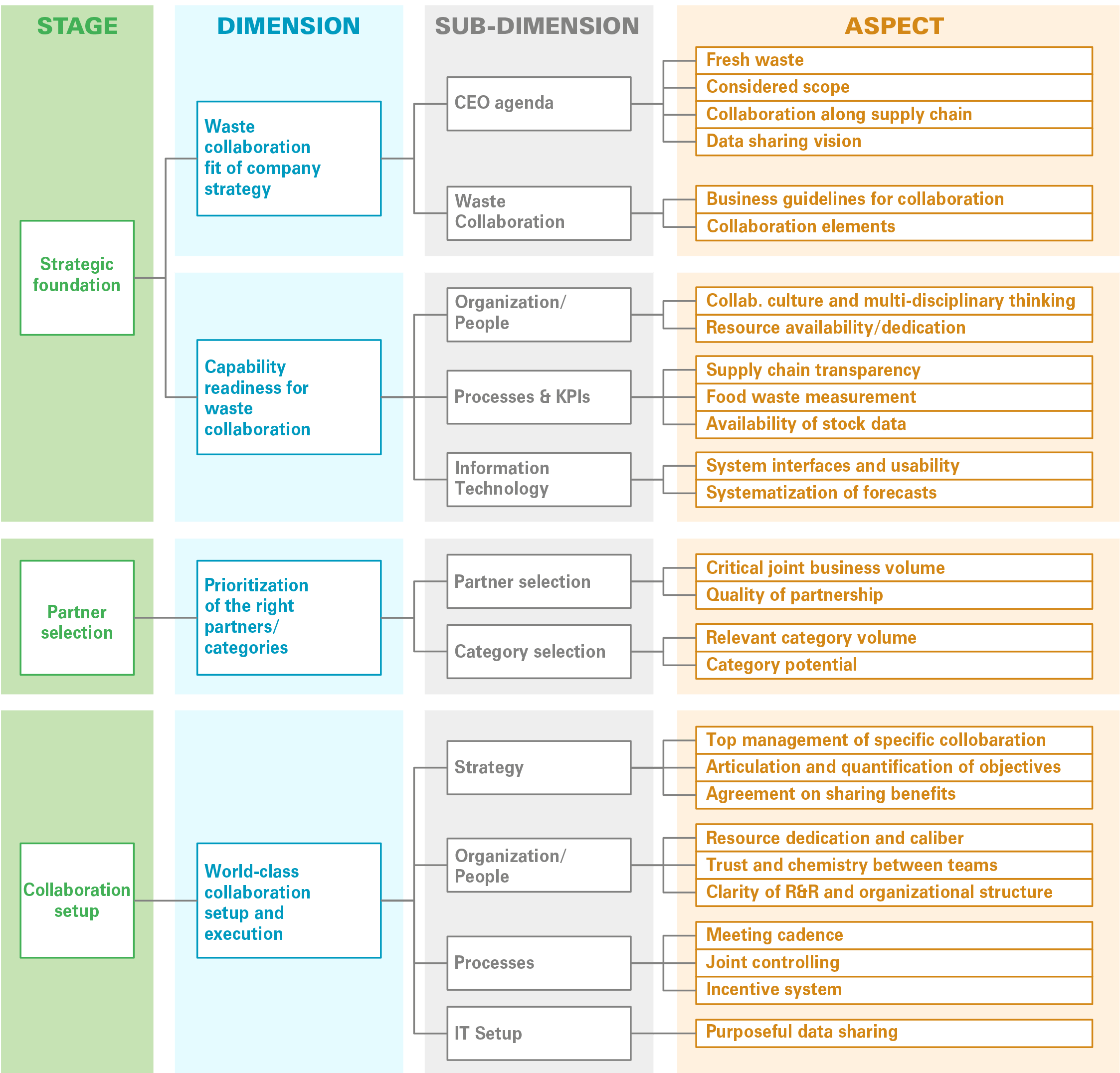

It then proposes organisations consider a new framework for collaboration that is made up of three stages; building a strategic foundation, selecting partners and finally, collaboration set up. The report then focused on the first stage, which broke down to two dimensions; the fit of collaboration on food waste on the company strategy, and the readiness and openness of the organisation to collaborative working. There were then five sub-dimensions, and then thirteen aspects.

The report then introduces a self-assessment questionnaire, that helps organisations assess the extent to which they believe that there is a strategic foundation in place to enable effective collaboration.

Finally, the report shares the aggregated data from 48 retailer and producers who completed the self-assessment form, which highlighted the strong relationship between the strategic intent from the head of the organisation for collaboration, and the organisation’s readiness, in short, organisation’s readiness follows strategic intent. The findings also highlighted that data availability and sharing are the most significant barriers to more effective collaboration on the opportunity to reduce food waste.

Abstract

This report, published in 2019, is focused on the way organisations can collaborate to reduce food waste in the supply chain. It highlights the benefits of working together, and the barriers to collaboration. The report introduces a new framework for effective collaboration and presents a self-assessment checklist for organisations to consider adopting when getting ready for a collaboration project. Finally, the report shares the self-assessment data on the readiness of a sample of retailers, presenting some benchmark data and highlighting how the sharing of, and availability data is the most significant barrier to more effective collaboration for this sample of organisations.

It draws upon in-depth interviews and focus groups from representatives of 13 retailers and producers, from UK, Germany, Netherlands, Belgium, Portugal, Czech Republic and Spain. The project team was assisted by the support of academics from Kuenhe Logistics University (KLU) and the Cardiff Business School.

The report highlights five major barriers to collaboration, namely; competing internal priorities, accessibility to data and transparency, food waste not identified in the joint business plan as a priority, failure to reach agreements on benefits sharing and finally, it came down to people, and the constant changes in key individuals central to any collaboration effort, and then the capacity and time to dedicate to a collaboration project.

It then proposes organisations consider a new framework for collaboration that is made up of three stages; building a strategic foundation, selecting partners and finally, collaboration set up. The report then focused on the first stage, which broke down to two dimensions; the fit of collaboration on food waste on the company strategy, and the readiness and openness of the organisation to collaborative working. There were then five sub-dimensions, and then thirteen aspects.

The report then introduces a self-assessment questionnaire, that helps organisations assess the extent to which they believe that there is a strategic foundation in place to enable effective collaboration.

Finally, the report shares the aggregated data from 48 retailer and producers who completed the self-assessment form, which highlighted the strong relationship between the strategic intent from the head of the organisation for collaboration, and the organisation’s readiness, in short, organisation’s readiness follows strategic intent. The findings also highlighted that data availability and sharing are the most significant barriers to more effective collaboration on the opportunity to reduce food waste.

Foreword

The ECR Community Shrinkage and On-shelf Availability Group is the flagship for collaboration on retail loss. Since 1999, we have delivered a constant stream of new thinking, tools and techniques that enable and prove the value of collaboration. However, there remains a huge opportunity for better collaboration to inspire new thinking and solutions, especially on food waste and markdowns prevention.

As one of our members bluntly shared: ‘we know that collaboration [to prevent food waste and markdowns] works, so why are we not doing more of it and really, what does it take to truly collaborate?’. To answer this challenge; we have undertaken a two-year study, with the help of academics and practitioners, to more deeply understand what is meant by collaboration, the benefits, the barriers and the critical aspects that define what is meant by sustainable collaboration.

Our findings conclude that there are three consecutive stages to collaboration, however, in this report we focus on the first stage – the strategic foundation that supports and enables effective collaboration. To help organisations take further advantage of this research, we have created an easy to use self-assessment tool which can be used internally and with possible partners to assess you and your partners readiness to collaborate. We hope you enjoy reading this report and using the self-assessment tool, and that it can help guide your organisation’s thinking on what it takes to collaborate with others.

Finally, I would like to thank the academics and all those companies that agreed to support this work – your contribution to helping the broader retailer and producer community to better understand this important issue is very much appreciated.

Executive Summary

Much has been said and written on the value of collaboration yet there remains a large gap between the vision and collaboration being a regular way of working for the industry. This research seeks to underline the value of collaboration while at the same time explaining why it is so hard to deliver in practice, examples could be the presence of competing internal incentives and the challenges of data sharing. More importantly, this research introduces a new framework that seeks to define what it takes to collaborate well.

This framework, developed by practitioners from retailer and producer organisations, plus academic and subject matter experts, is made up of three consecutive phases:

1: The Strategic Foundation – Are you ready to collaborate?

2: Partner Selection – Who do you want to collaborate with and on what product categories?

3: Collaboration Set Up and Execution – How should you organise and execute collaborative projects?

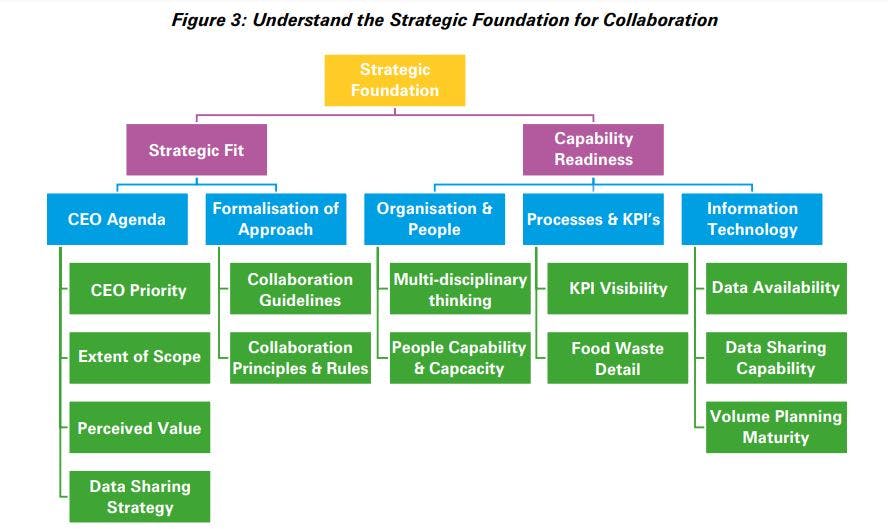

This report focuses primarily on the first stage, the Strategic Foundation, and is made up of 13 identified aspects of collaboration that the group concluded can explain the extent to which organisations are ready for collaboration. These aspects aggregate up to five sub-dimensions and in turn, to two higher level dimensions.

The first of these two higher level dimensions is the Strategic Fit of food waste and collaboration to the C-Suite agenda. The second is Capability Readiness, and the extent to which there is multi-disciplinary thinking, people with the right amount of dedication and the availability of and willingness to share data, at the right level of detail and granularity, between organisations, to inform decision making.

The report introduces a new self-assessment tool to help organisations, inspired by International Standard for Collaborative Working (ISO 44001 Collaborative Business Relationship Management Systems), it can help organisations assess their own and their potential partners readiness to collaborate.

The responses from 48 retailers and suppliers to the online self-assessment tool were analysed and the full results shared in this report. The two key conclusions from this analysis are that 1) Capability readiness does indeed follow strategic intent. Said another way, when the respondents reported that the C-Suite of their organisations had prioritised food waste & markdowns, embraced an end to end approach and saw collaboration as a lever for improvement, they were more likely to report a higher level of capability readiness. And 2) That the availability of data remains mostly topic or project specific and the ability to share data between organisations is mostly a manual process and only somewhat automated, potentially limiting the ability to collaborate with others.

Retailer and supplier organisations are encouraged to use the self-assessment Excel-based tool to initiate discussions on collaboration internally and with their partners, and to identify the extent to which their respective organisations have in place a strong strategic foundation for collaboration.

The tool is available from the following website. www.ecr-shrink-group.com

Introduction

Shoppers entering any supermarket in Europe today will expect to see a mouth-watering display of fresh food. The abundance and breadth of assortment reflects their desire for choice, quality and freshness. However, the excessive supply required to build these beautiful displays and to offer the shoppers such a wide choice of high quality, fresh products on the shelf comes at a cost, especially food waste.

ECR estimates the cost of food waste and markdowns1 for European retailers to be over €13 billion a year, which represents 1.64% of total retail sales. This includes both the cost of the last-minute discounts needed to sell the products before they expire and the cost of the products that need to be disposed of, either by being donated to charity, recycled, fed to animals, recycled or sent to land fill. Other academic research sponsored by ECR has also helped bring greater visibility to the financial implications of the trade-offs between availability and waste2 and identified 65 practical tools and techniques to enable retailers to sell more and waste less3.

However, many of these interventions require retailers and suppliers to work together more closely and to innovate. For example, to reduce case sizes, retail buyers and logistics teams need to work with their supplier’s supply chain and commercial leaders. The aim of this new research is to define what good collaboration looks like, and to directly address the question: what does it truly take for retailers and suppliers to collaborate effectively.

In the first section of this report, we explore the reasons to collaborate, the benefits and the current barriers. In the second section, we introduce the three-stage collaboration framework and detail the 13 aspects of the strategic foundation to collaboration. In the third section we introduce the self-assessment tool. In the fourth we share the results from an initial survey of 48 retailers and suppliers, to provide some benchmark data and initial conclusions. The final section proposes some practical recommendations for organisations reading this report.

Methodology

Initiated in February 2017, this co-productive research was undertaken in the form of a series of focus group sessions, pilot studies with three multi-national organisations and 48 responses to an online survey. The initiation of the project and the first focus group took place at the Kuehne Logistics University (KLU) in Hamburg on Feb 9th, 2017. The second was held at a Tesco store in Slough in the UK on June 20th, 2017, while the third was held at the University of Economics in Prague on November 30th, 2017. The final focus group session was undertaken back at KLU on June 7th, 2018. The online survey was issued in January 2019.

After each focus group, a sub-group met, shared their notes and appointed a single leader to create a draft report that captured and shaped the findings and insights. This process was then repeated after each focus group, through to the completion of this final report. The sub-group that oversaw the development of the model from the beginning to the end was made up of the following experts:

Sub-Group – Food Waste Collaboration

- Name - Mr Colin Peacock (Leader)

- Title - Group Strategy Coordinator

- Organisation - ECR Community

- Name - Mr John Fonteijn

- Title - Head of Global Asset Protection

- Organisation - AholdDelhaize

- Name - Prof. Dr. Sandra Transchel

- Title - Professor of Supply Chain and Operations Management

- Organisation - Kuehne Logistics University (KLU)

- Name - Dr Jane Lynch

- Title - Purchasing and Supply Management

- Organisation - Cardiff Business School

- Name - Mr Dustin Wisotzky

- Title - Principal, Retail & Consumer Goods

- Organisation - Oliver Wyman

The focus groups consisted of food waste prevention experts from the following companies:

- Albert Heijn, Netherlands

- Albert, Czech Republic

- Asda, United Kingdom

- Carrefour, Belgium

- Coop, United Kingdom

- Delhaize, Belgium

- Danone, Spain

- Lidl, Germany

- M&S, United Kingdom

- Ocado, United Kingdom

- Sonae, Portugal

- Tesco, United Kingdom

- Waitrose, United Kingdom

Food Waste Collaboration

What is Collaboration and Why Collaborate?

The word ‘collaboration’ teams up the Latin words, ‘com’ (with, together, jointly) and ‘laborare’ (to work) to form the word collaborate and to mean working together. In the context of food waste prevention, we define collaboration as retailers and suppliers working together to co-create new interventions that prevent waste, in ways that would otherwise not be possible or imagined.

The Chartered Institute of Collaborative Working (ICW) noted, “Collaborative business relationships have been shown to deliver a wide range of benefits, which enhance competitiveness and performance whilst adding value to organisations of all sizes”. The premise and underlying assumption of this research is the same, and that collaboration can be an effective way of discovering and delivering new and innovative interventions to the problem of food waste and markdowns. This assertion is underlined by public statements by most industry leaders, including Dave Lewis, the CEO of Tesco.

“At Tesco, we’re committed to tackling food waste not only in our own operations but also through strong and effective partnerships with our suppliers and by helping our customers reduce waste and save money.”

The Role of (Better) Collaboration in Reducing Food Waste

There is much that retailers and suppliers can do to reduce food waste on their own and without the need to work with others. There is also much that can be delivered by working more closely with others outside of your own organisation. Four examples of how food waste can be reduced via collaboration between retailers and suppliers are shared below.

- New Product Innovation: Retailers and suppliers can jointly develop new products that can appeal to consumers and at the same time reduce waste. Examples could be new products with an extended shelf life or new products that use ingredients that would otherwise be wasted.

- New Packaging and Case Sizes: Retailers and suppliers can jointly develop different packaging and case size configurations that could help reduce waste without dampening the consumer proposition or add cost to the operation. Examples could be new packaging that better protects product from risk of damage, allows the consumer to use just one portion or smaller case sizes to increase distribution.

- Joint Forecasting and Replenishment: Retailers and suppliers can jointly work together to produce more accurate volume demand forecasting that would minimise over-supply to the store while avoiding excessive levels of lost sales. An example could be retailers sharing a live feed of hourly EPOS sales data directly with their suppliers to help ensure supply and production can more closely match consumer demand.

- Joint Short-term Demand Generation: Retailers and suppliers can jointly work together to manage crop flushes and to re-purpose the parts of the crop that does not meet the cosmetic standards demanded by consumers.

Case Studies in Collaboration

To illustrate the benefits and results from collaboration, the research team have started to collect evidence from joint projects in the public domain, below are three case studies:

Case Study 1:

One manufacturer and retailer worked collaboratively to create a new product made up of unused raw materials, thus saving those materials from being wasted. This new line item is now being sold in the retailer’s stores.

Case Study 2:

A manufacturer and retailer collaborated to improve the percentage of every crop that was consumed by re-purposing and processing the off standard and odd shaped products into other products such as ready-made meals and frozen varieties of the product that would then be sold in the retailer’s stores. This collaboration prevented significant quantities of product being fed to animals or thrown away, while also improving profitability for both organisations.

Case Study 3:

To help avoid a possible high level of waste in the field caused by a bumper harvest of cauliflowers, and despite the risk of more food waste in the stores, one retailer responded to the cauliflower flush by introducing new in-store promotions (recipes, extra displays and price discounts) to increase sales and overall waste.

Despite these success stories in supply chain management, a greater adoption by more organisations of collaborative working, across more fresh categories, remains a significant opportunity. It is also the case that many organisations still report that their relationships with their retailer or producer partners are still adversarial; that data sharing is not smooth or regular, and that uncertainty in the relationship and a lack of trust remains high.

So, what is getting in the way?

‘Imagine a supermarket will say it wants 10,000 packets of strawberries. On Monday and Tuesday, the food is accepted. On Wednesday, the food is rejected. When produce is not selling well – perhaps it is raining, and nobody is buying the strawberries – the supermarket rejects the consignment, but there is no difference in the actual strawberries. Believe me, I have seen it happen time and time again….’

An anonymous European strawberry producer supplying UK supermarkets

Understanding the Barriers to Collaboration

The focus groups identified five key barriers to collaboration:

- Competing Internal Priorities

Competing internal priorities get in the way when interventions that for the total company may help the organisation improve waste can be blocked by any one function if it has a negative impact on their own objectives. An example could be case size reduction: For the store, a smaller case size can very often help to reduce waste by removing the risk that the product will not sell out before the shelf life expires. However, this adds cost to the supplier, leading to a higher cost of goods and a lower gross margin for the buyer, and increased logistics costs for the supply chain. If the priority is to lower logistics costs, then smaller case sizes may be de-prioritised.

As one retailer in the focus group stated: ‘we cannot collaborate internally, let alone hope to be able to collaborate well with external partners, which is a response that is not unusual for many managers executing collaborative ways of working. The practitioners and academics supporting this research underlined the challenges with internal collaboration with further examples, and that getting it right is an important prerequisite for effectively collaborating in the supply chain. - Data Sharing and Transparency

Accessibility and transparency to meaningful data was also called out as a significant barrier, explained sometimes simply because there is no data, or a means by which to share. However, for some organisations, the principle of data sharing with others has either been considered and deemed not to be appropriate or a policy has yet to be established. The fear of the data getting into the hands of competitors and foregoing potential revenue from data sharing were two specific examples of reasons why data sharing was off the table for many organisations. - Joint Business Plans

The focus group discussions revealed that food waste, and collaboration on waste was rarely included as a metric for consideration in joint business plans. Unless prioritised at the highest level, and documented, the focus groups concluded that collaboration is unlikely to grow and deliver benefits other than those that can be achieved by just good coordination. Said differently, collaboration can be perceived as a process that slows down progress while coordination is seen as a planned activity that delivered results in a controlled way. - Benefit Sharing

While there are case studies that demonstrate that collaboration can unlock huge value for all parties, Tesco and Branston being an example , the research found that often projects failed to get off the ground at the very start as organisations fail to reach agreements on how to split any benefits that may be realised or additional costs that could be incurred. - Consistency and Capacity

Collaboration is about long term thinking however suppliers’ category managers and buyers are often tasked to think short term; they are often not that long in any one category role, sometimes less than 18 months, and very practically, with sometimes more than 30 vendors for any one category, there may simply not be the time to be part of any collaboration projects.

The Strategic Foundation for Collaboration

To unlock the benefits of collaboration, the group identified three stages of collaboration (Figure 2).

The three stages are:

- The Strategic Foundation – Are you ready to collaborate?

This foundational stage is about whether collaboration as a strategy fits with the corporate priorities and the capability of the organisation. - Partner Selection – Who do you want to collaborate with and on what categories?

This second stage is about selecting the right categories and partners for collaboration projects. - Collaboration Set Up and Execution – How should you organise and execute collaborate projects?

The final stage is about how organisations should embed collaboration and joint projects into their ways of working to include project governance, resource allocation, project management disciplines and IT set up.

This research report and its outputs are focused on the Strategic Foundation stage, and a deep understanding of the two dimensions that define an organisation’s readiness to collaborate, namely, the fit with company strategy and capability readiness (Figure 3).

These two dimensions have then been broken down into five sub-dimensions, and then 13 aspects. The next sections provide detail on these sub-dimensions and aspects

Strategic Fit – Waste Collaboration Fit with Company Strategy

CEO Agenda

Food Waste Fit with CEO Priority

Strategic priorities are set by the executive management with the CEO held accountable for the delivery of these priorities. When food waste and markdowns are a corporate priority for the Board and the CEO, and where that priority is communicated in public statements, collaboration will be a more relevant proposition, and one that can command resources and a sense of urgency for results. Conversely, where there is no clear priority for food waste and markdowns, it follows that collaboration will be less relevant as a strategy.

Extent of Scope

Food waste occurs at all points in the supply chain journey, from the field all the way through to the consumer’s home. Organisations, perhaps especially those with scarce resources, may choose to tackle those aspects of food waste that occur just ‘within their own four walls’ to deliver immediate improvements without the need to involve or collaborate with others.

Others, may choose a fuller scope, embracing aspects of the supply chain beyond their own four walls. This more ambitious scope will require the need to engage with other partners, which for retailers may be their suppliers or shoppers. The larger the scope, the more relevant collaboration will be to the delivery of improvements, and the more likely that resources will be allocated to foster and deliver that collaboration.

The Business Case for Collaboration/Perceived Value

Successful collaboration needs an investment in resources, a commitment to share proprietary data, possibly intellectual property or other early stage thinking that could be considered ‘company secrets’. Further, deep collaboration also requires the acceptance that progress may potentially be slower than with other less collaborative approaches to innovation. Organisations need to be convinced that the ‘prize’ from collaboration more than covers the cost of the investment in time and money. Those that have previously proven the value of collaboration or who have deeply held beliefs that there is a business case for collaboration will be more open to collaboration and new ways of working.

Conversely, collaboration will be unlikely to be relevant to those organisations who have yet to realise any benefits from previous collaborations, have had bad experiences from previous collaborations or who simply do not believe that any possible ‘prize’ from collaboration justifies the time and expense.

Data Sharing Strategy

Whether or not to share proprietary data with others as a strategy is a major decision for organisations. Some organisations elect simply not to share data at all, whereas others, for example Walmart, view sharing data with their vendor partners as a strategy for growth. The extent to which data can and will be shared with others will be the key to determining the value that can be delivered by collaboration. There needs to be a clear and agreed purpose for sharing data to enhance the collaboration.

Formalisation of Approach

Business Guidelines for Collaboration

Organisations intent on leveraging collaboration as a strategy will develop and communicate internally business guidelines on collaboration. These will identify the role that collaboration plays in delivering corporate priorities, and with which organisations any collaboration will be prioritised and the expected benefits. In the absence of clear business guidelines, organisations may hesitate and be unable to unlock the true potential of collaboration.

Collaboration Principles & Rules

Collaboration is an investment not only in resources and time but also trust. Clear principles and rules help ensure organisations are compliant, that all confidential data and company secrets are protected, and where there are gains, there are clear principles agreed up front on how those benefits can be shared between organisations. Collaboration in organisations where these principles and rules are explicitly stated are more likely to succeed than in those organisations where they have not been fully considered and made explicit.

Capability Readiness for Waste Collaboration

Organisation and People

Collaborative Culture and Multi-disciplinary Thinking

It is often easier for any single organisation, function and individuals to work in isolation on what matters most to the achievement of their own performance metrics. Collaboration in organisations where there is not a culture of working together and where incentives are misaligned is unlikely to prosper. For example, a buyer working in isolation of others may be unlikely to accept a higher cost of goods and lower gross margin for a product improvement that has a longer shelf life in the store if there is no direct benefit on their own scorecard from reduced food waste and where gross margin is being prioritised by the buyers functional leader.

Conversely, organisations where there is a culture of working together and where incentives are aligned, are likely to be very well set up for successful collaboration.

People Capacity and Dedication

Collaboration requires leadership, dedication and capacity. Where this is all available, collaboration can thrive, where it is not, collaboration will simply remain an aspiration.

Processes and KPIs

Food Waste Measurement and Transparency

The extent to which organisations measure food waste and are prepared to share openly with others will be a significant factor in determining the health and productivity of an investment in collaboration. With data, organisations can have clear, unarguable metrics to guide the joint work. Without data, any joint work will be problematic as the benefits delivered by collaboration and any return on the investment will be hard to quantify

Level of Food Waste Data Detail

The more granular the data on food waste, the greater the visibility to the possible reasons and root causes of the food waste problem, and it follows, the more likely that the right interventions can be identified, and their impact measured.

Availability of Food Waste Data for Collaboration Efforts

The design of data systems and hierarchies rarely consider the requirement at some point in time to share data with others, hence when requests for data sharing are received from another organisation, it is often very hard to extract the exact data required for the collaboration to succeed.

Information Technology

Data Sharing Capability

Collaboration between organisations who each have available the right data at the right level of detail may still not be optimised if the means by which to share that data cannot be made freely available, in a way that is simple and effortless. Conversely, any collaboration is made more difficult when every data request has to be submitted and then agreed on a case by case basis, with the data manually extracted and shared in a file between respective partners.

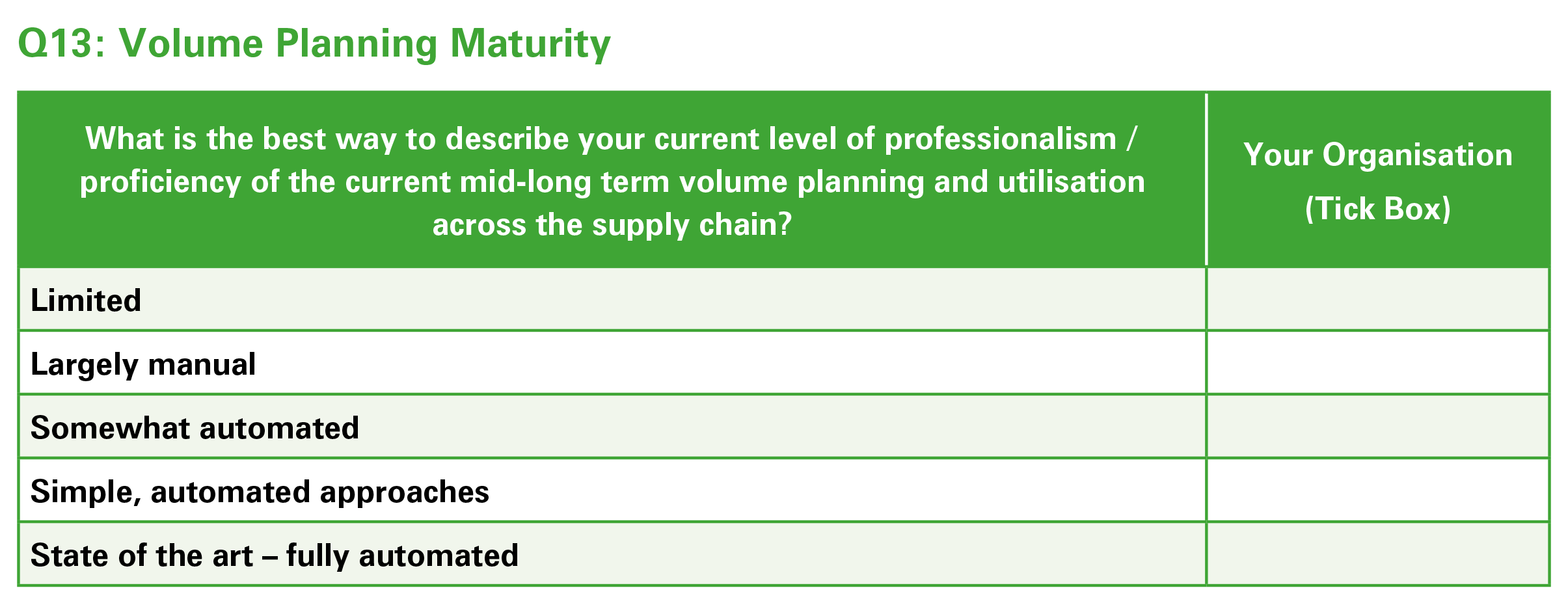

Proficiency of Volume Planning Capability

The extent to which organisations are able to collaborate together on one of the key levers of collaboration on food waste prevention: volume planning, will in part be dependent on the proficiency of the forecasting tools, and the sharing of information. Where organisations have dedicated ‘state of the art’ forecasting tools that can inform mid- to long-term volume planning, and a commitment to information sharing, collaboration can succeed.

Introducing the Collaboration Readiness Self-Assessment Tool

Consistent with previous ECR research, this project carried with it a commitment to deliver practical tools the industry can adopt. In this case, these tools are in the form of an online survey and an Excel-based self assessment tool. Their purpose is to help organisations gain an understanding of the extent to which there is a strategic foundation in place for effective collaboration. The fundamental underlying assumption in the tool is that the greater the ‘score’ the greater the extent and strength of the strategic foundation for collaboration. Conversely, the lower the ‘score’ the weaker the extent of the strategic foundation for collaboration.

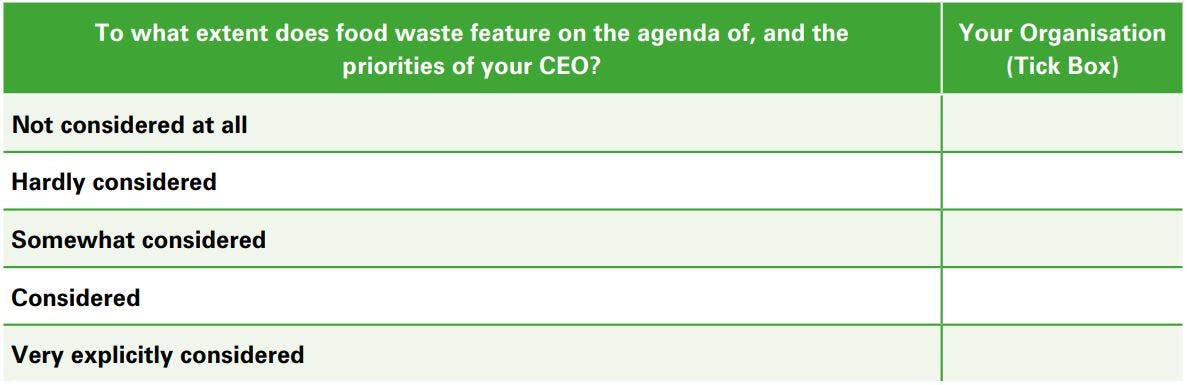

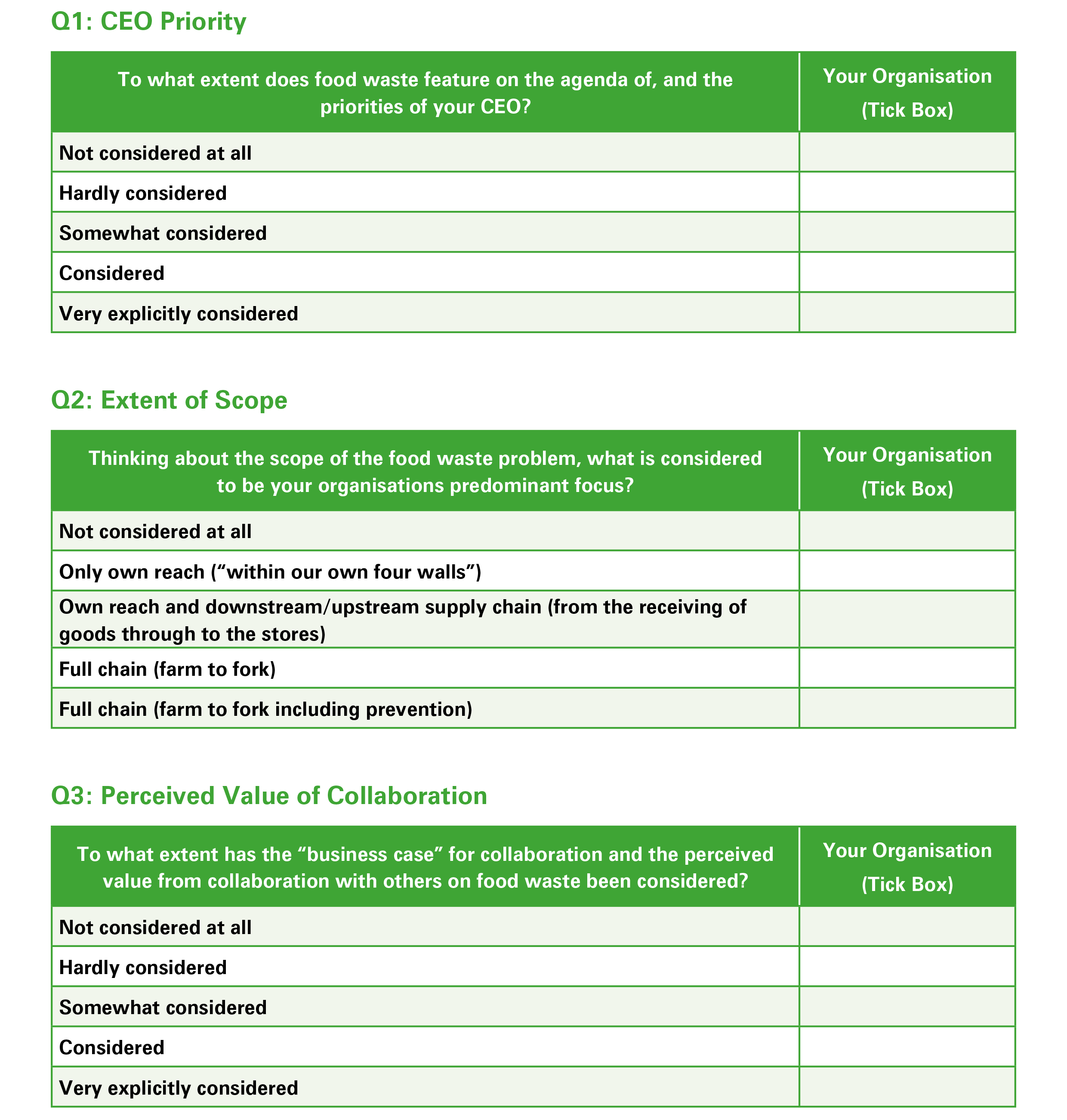

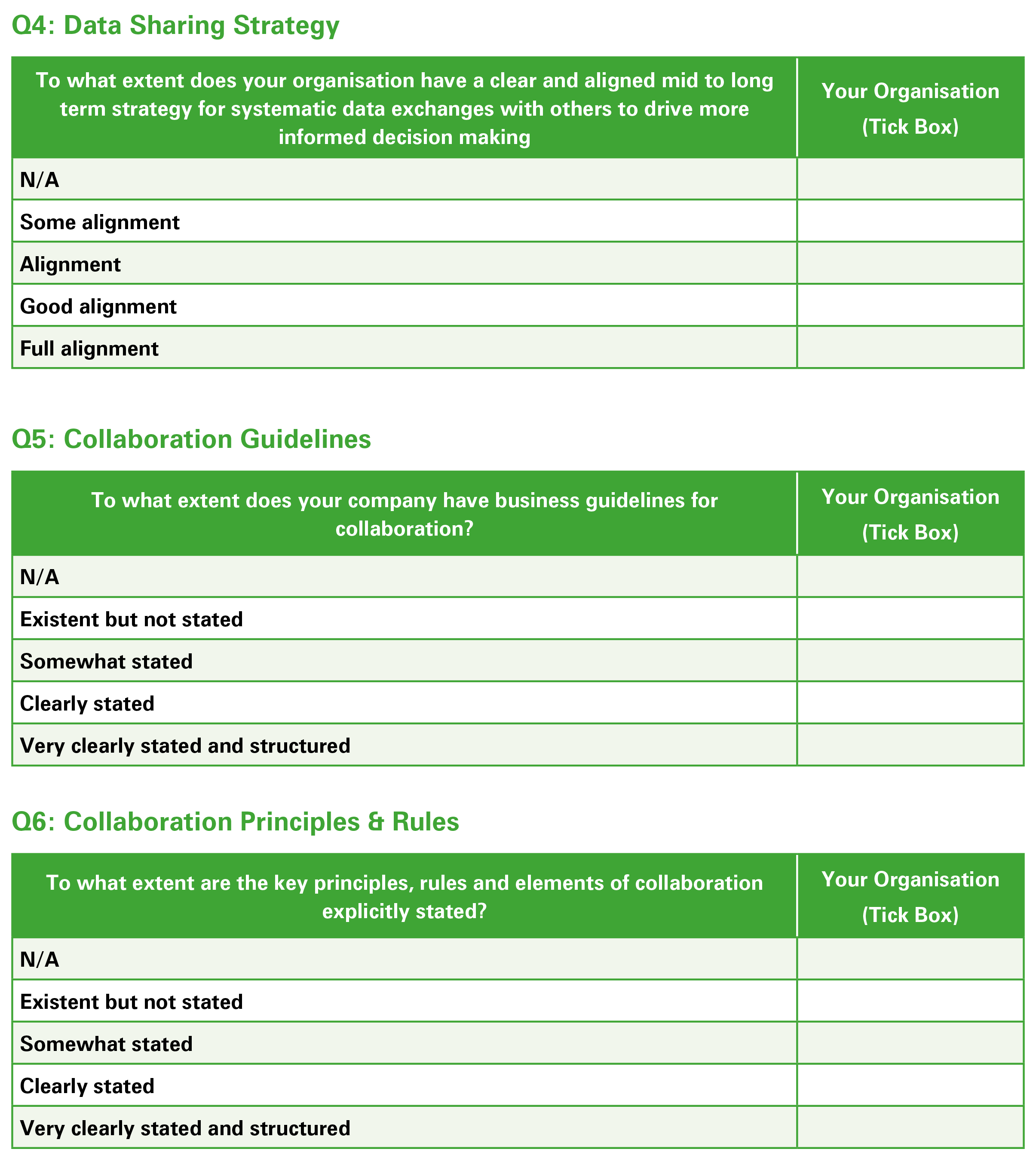

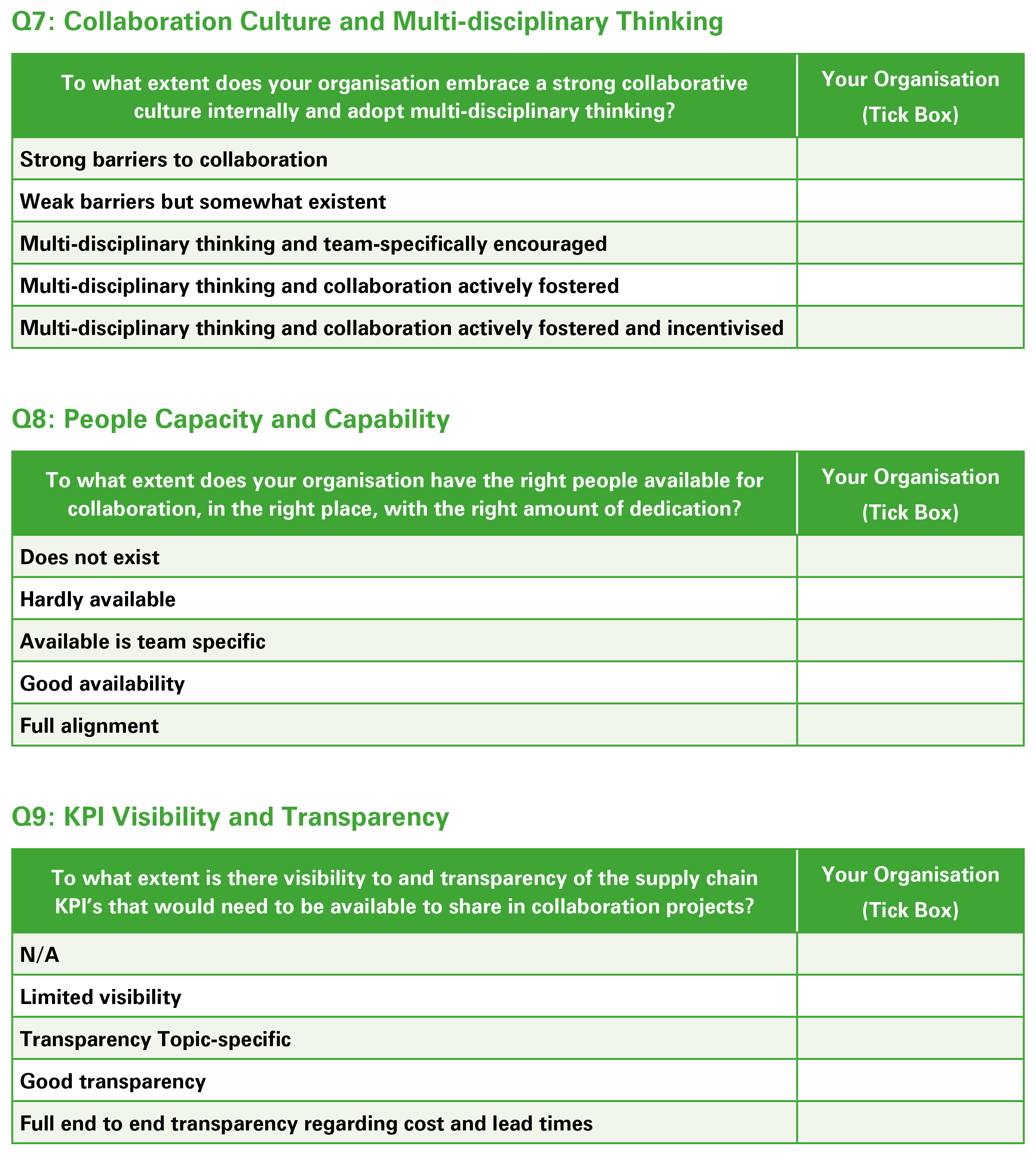

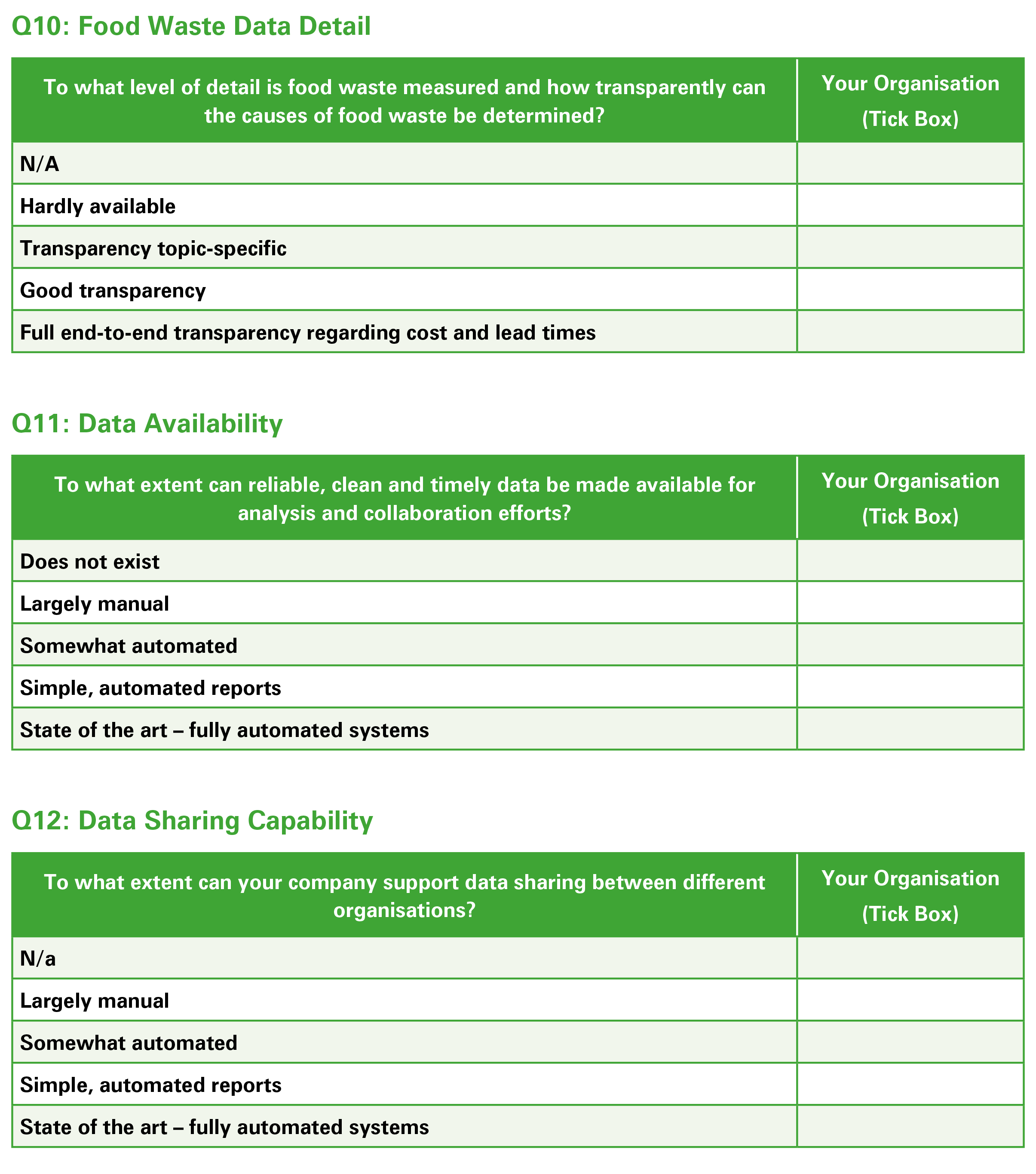

The tool looks at the two dimensions of strategic fit, and capability readiness, and in line with the framework (Figure 3) under the dimension of strategic fit, there are 4 questions on aspects of the CEO Fit and 2 questions on the Formalisation of Approach. Under the dimension of capability readiness, there are 2 questions on Organisation & People, 2 questions on Processes & KPIs and 3 questions relating to Information Technology. In total, there are 13 questions. By way of example, the first question on the self-assessment tool reads as follows:

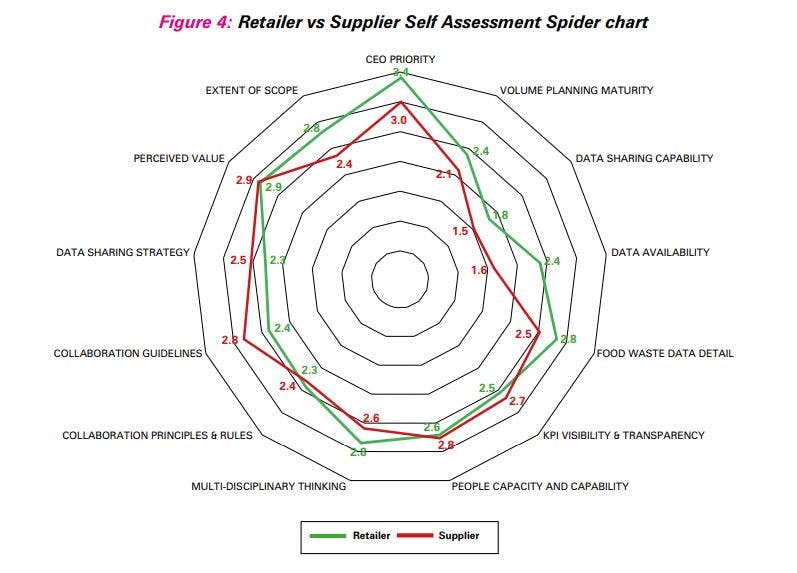

Respondent are asked to provide an answer to each of the 13 questions, the scale is 0-4, so in this case, ‘not considered at all’ would score a 0 while ‘very explicitly considered’ would score a 4. A score is then calculated for each question, and then the scores for all 13 questions can be displayed using different visualisation techniques from a bar graph to a spider map as per below. Spider maps can be very helpful when you want to display the individual scores of different managers, departments or organisations. In this case, the score can be compared to the benchmark data collected in this research from 48 respondents.

Using the spider chart Figure 4, organisations can discuss the findings and potentially reach conclusions on the answers to questions such as:

• Should we really initiate this collaboration project when these results suggest we are not ready?

• How can we start to close the gaps that are going to be barriers to any successful collaboration project?

• As we survey the wreckage of previously unsuccessful collaboration projects, does this analysis help provide the explanations as to why they failed?

The questions in the survey on the 13 aspects are listed in the Appendix. The Excel tool and online survey can be downloaded and accessed from the ECR website: www.ecr-shrink-group.com

Pilot Results

To understand the relevance and ease of using the self-assessment tool, an online version of the selfassessment tool was sent to those retailers and suppliers who have participated in the ECR working group meetings on food waste and markdowns prevention.

48 responses were received and analysed. Some 36 of the respondents were retailers, 12 were suppliers, in that they were either a wholesaler, producer or farmer. From a functional perspective, 25 of the 48 respondents worked in a supply chain management function; other functions represented included marketing, category management, store operations and loss prevention.

Key Findings

1. Consistency in Results Between Retailers and Suppliers but Differences also Apparent

When the results across each of the 13 aspects are reviewed, there was close alignment between retailers and suppliers on many aspects, for example the perceived value of collaboration, with each sharing that this had been considered or very explicitly considered by their organisations.

However, there were some differences:

- On the aspect of the CEO Priority and Extent of Scope, the respondents from retailers reported a slightly higher level of priority and a greater ambition on the scope of the problem they wanted to focus on, with suppliers just a bit less ambitious with 7 of the 12 respondents from suppliers reporting their scope to be that which is within their own reach compared to 18 of the 36 retailers

- On the aspect of data availability, as we willdiscuss, both retailers and the supplier respondents reported that making clean and reliable data available for sharing remains largely a manual process rather than a fully automated state of the art system. For suppliers, 8 of the 12 respondents shared that their approach to making data available for sharing was largely manual or somewhat automated, compared with 18 of the 36 retailer respondents.

- On the aspect of collaboration guidelines, this was the one aspect where the respondents from suppliers were more likely to have clearly stated guidelines for collaboration. Nine of the 12 supplier responses reported that they had clearly stated business guidelines for collaboration while only 14 of the 36 retailers stated they had clearly stated business guidelines.

2. Data Sharing Capability Remains a Key Barrier to Greater Collaboration

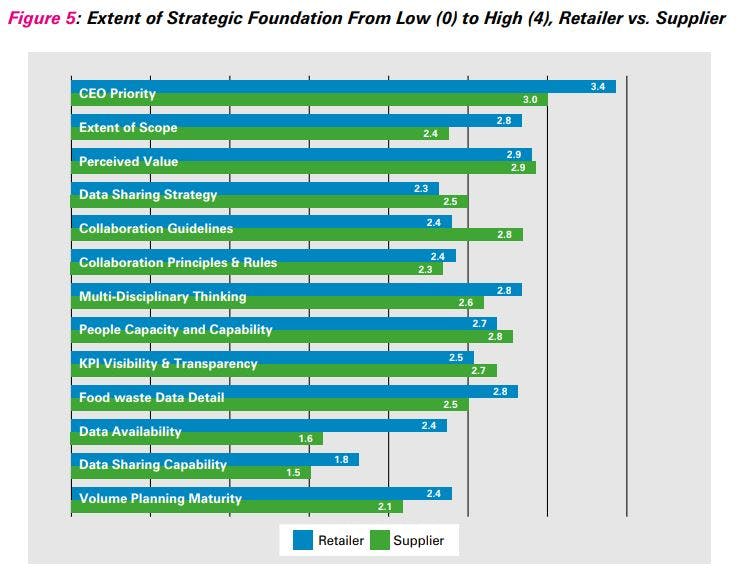

When the responses from the retailers against all 13 aspects are reviewed (Figure 5) what emerges is that the problem of food waste and markdowns scored strongly on the sub dimension of CEO Fit, especially on the question of the extent to which food waste and markdowns is declared to be a corporate priority by the CEO, with the average score being 3.4 (the maximum score being 4). In fact, 15 of the 36 retailer respondents said that food waste and markdowns as a priority were very explicitly considered.

On the other hand, data sharing capability was the aspect that had the lowest score at 1.8 out of 4, meaning that the majority of the retailers reported that data sharing was largely a manual process, very project specific and on a request only basis. In fact, only 2 of the 36 retailers indicated that their organisation had a ‘state of the art’ and fully automated system for sharing data. The low score on data sharing capability amongst retailers is not a surprise given the relatively low scores of 2.3 for data sharing strategy, where only 7 of the 36 retailers indicated that they had a clear and aligned strategy. Equally, data availability only scored 2.4, with only 3 of the 36 retailers indicating that they had a state of the art/fully automated means to make reliable, clean and timely data available for analysis and collaboration efforts.

Taken together, these three aspects indicate that there is neither perfect alignment amongst these retailers to a strategy to share data, and it follows that only a few of the respondents reported that they had invested in capabilities to make clean, reliable and granular data available for collaboration, and the systems needed to enable the sharing of the data in a fully automated way with others, such as suppliers.

More optimistically, the high scores for the aspects on CEO prioritisation, the extent of scope and the perceived value of collaboration could indicate that there is a growing sense of urgency for collaborative working coming from the C suite (Figure 6). This in time could lead to greater clarity and alignment on data sharing strategies, with subsequent investments in state of the art systems to make clean, reliable data available for collaboration, and eventually fully automated systems that can enable the easy transfer of data between organisations, more likely. However, for this sample of retailer respondents, it could be said that despite a strong strategic intent, the challenge of data sharing remains the ‘Achilles heel’ of collaboration.

3. Strong Correlation Between the Strategic Fit and Capability Readiness

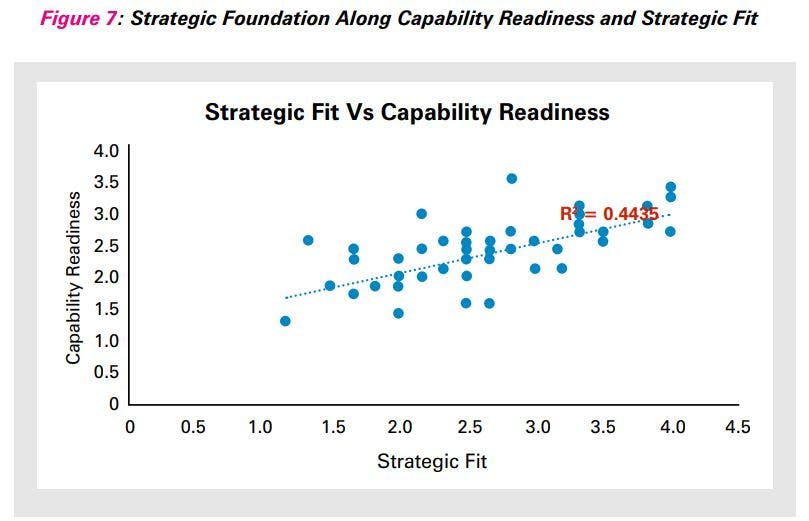

Plotting all 48 respondent’s data on strategic fit and capability readiness (Figure 7) further analysis looked to explore the relationship between the two, and test the hypotheses that respondents who score their organisation higher on strategic intent are more likely to also score them highly on capability readiness.

As can be seen, simple linear regression analysis suggests there is a relationship between the two factors, with an R2 score of 0.44, suggesting that there is a 44% chance that this is a meaningful relationship. What it does not explain, however, is whether this positive correlation is explained in full as there could be other explanations of this relationship between strategic fit and capability readiness. That said, a good working assumption could be that there is a causal relationship, and that capability readiness will follow only when collaboration is declared a priority by the CEO, when there is clarity and alignment to collaboration and data sharing, when the correct resources have been allocated to deliver collaboration, and there is a set of well considered guidelines and principles in place.

Indicated Actions and Future Research

Organisations are encouraged to use the tool, which is freely available from the ECR website (www.ecr-shrinkgroup.com) to: • Conduct a pre-check on any possible collaboration project to prevent possible failures.

• Review current collaboration projects to jointly assess their current ‘health’ using the self assessment tools. Organisations are also asked to share back the results and outcomes of the above with ECR.

Looking ahead, two new research projects could be investigated:

1: Proving the Value of the Self-assessment Tool

Using a case study approach, 3-5 organisations would share how they used the self assessment tool in their operations. Was it fit for purpose? Did it generate insights that could be acted on? What was the value of using the tool? Did it save time and money?

2: Validating the Strategic Foundation

Based on established and successful collaboration partnerships, researchers could seek to deconstruct, based on interviews and site visits, the critical elements of collaboration to understand from real world examples, the habits of those who are ready for collaboration.

Appendix I: The Three Stages Overview

Appendix II: Self-Assessment Questions

Main office

ECR Community a.s.b.l

Upcoming Meetings

Join Our Mailing List

Subscribe© 2023 ECR Retails Loss. All Rights Reserved|Privacy Policy